The tricky politics of transit-oriented development in Northern Liberties

Last Wednesday’s morning news roundup led to an interesting discussion with PlanPhilly contributor and Northern Liberties Neighbors Association President Matt Ruben about whether it was fair to characterize opposition to an industrial building conversion with 47 bedrooms and no parking in Northern Liberties as NIMBY politics.

NLNA’s zoning committee felt it had no choice but to reject a variance request to build 28 lofts in an industrial building at 1133 N. 4th Street due to the lack of parking in the proposal. The site is currently zoned I-2 industrial, which doesn’t allow housing, and will soon be zoned IRMX, which allows housing, but requires a 1:2 parking ratio – 14 spaces, in this case. The developer proposed zero, and said the building would be marketed to the growing car-free population in Philly.

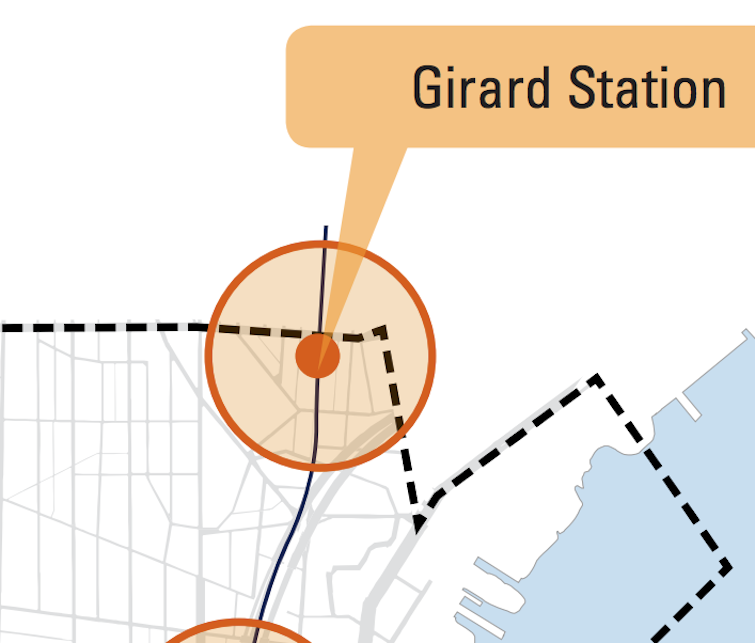

The site is just four blocks away from the Girard Avenue El station, half a block from the Rt. 15 trolley, and half a block from two Rt. 57 bus stops – seemingly the Platonic ideal of a location for housing targeted to car-free transit and bike commuters. Few places in the city seem better equipped to handle more density without inviting in more cars.

But after listening to Matt’s explanation of the tough position the zoning code can sometimes put neighborhood groups in, I’m persuaded there are important obstacles to transit-oriented development in the river wards that are larger than one neighborhood zoning advisory board could hope to solve.

Here are three.

1. The politics

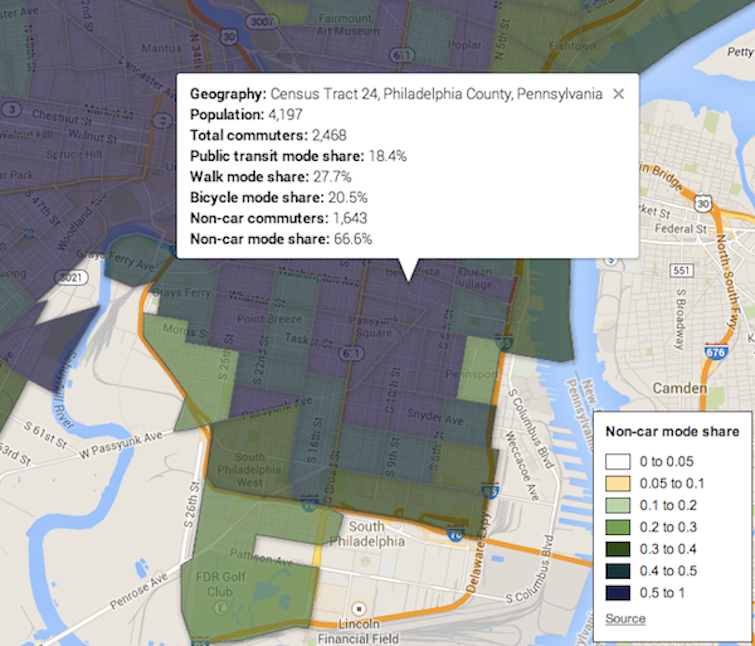

The first thing to understand about Northern Liberties land use politics is that the current mode share split between car, transit, bike, and pedestrian commuters makes transit-oriented development a hard sell. Throughout greater Center City, non-car commuters make up at least a majority in most census tracts, and are a supermajority in many.

In my neighborhood in Bella Vista, two-thirds of my immediate neighbors get to work without a car. Parking is still a potent issue, but it’s a potent issue for about a third of the neighborhood:

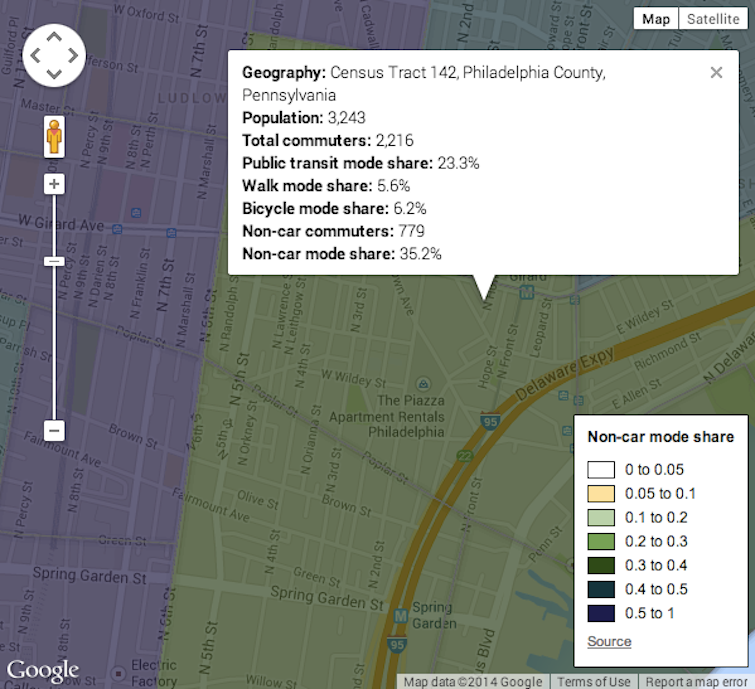

In Matt’s neighborhood, it’s the reverse. In the two Census tracts that overlap Northern Liberties (367 and 142), the non-car commuter mode share is 37.9% and 35.2%, respectively:

The fact of the car-commuting supermajority makes the politics of transit-oriented development difficult to maneuver in the absence of committed political leadership, since the name of the game for TOD is parking attrition, and higher building density on transit-adjacent land.

Ruben says even though the advisory-only NLNA zoning committee supports TOD in concept, approving a variance request for zero parking spaces would go further than the code, or even a hypothetical TOD overlay.

“Our zoning committee is very much in favor of TOD and understands the importance of it, but it makes it really really hard for a community organization when the baseline of the zoning code says you have to have 1:2 parking,” he explained.

“That makes it impossible for a zoning committee to sell zero parking to neighbors, and you can’t just trample all over all the neighbors and say we’re going to do the diametrical opposite of what you’re screaming about, and say fine with zero.”

2. The code

While the new code does pay lip service to TOD as a policy goal:

The Transit-oriented Development (TOD) standards of this section are intended to encourage urban growth patterns, opportunities for increased transportation mode choice, reduced reliance on the automobile, and a safe and pleasant pedestrian envrionment. The regulations help ensure an attractive streetscape, a functional mix of complementary uses and provision of amenities that support the use of transit, bicycles, and pedestrian facilities.

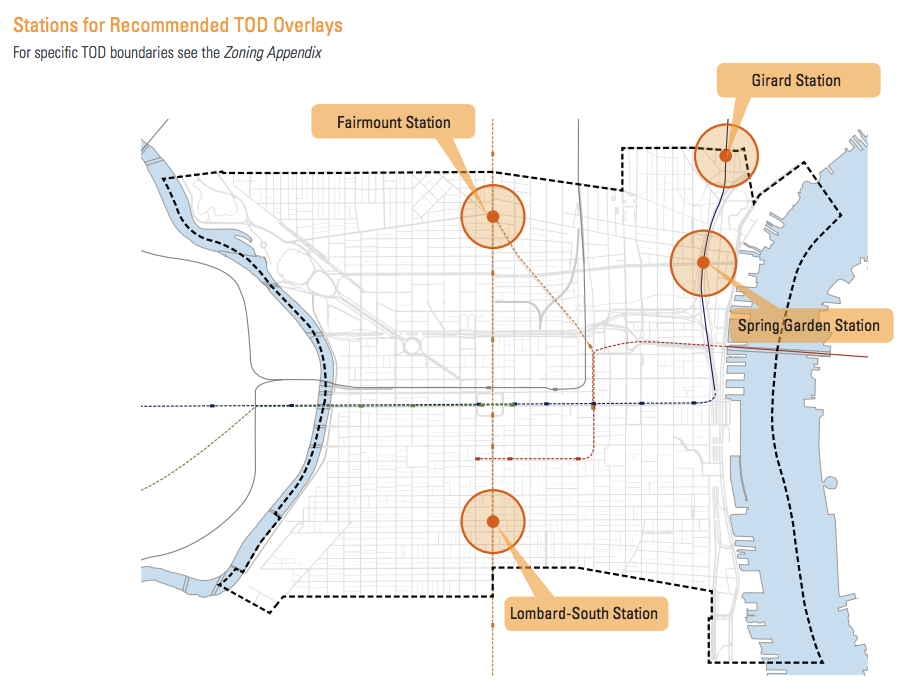

And the Central District Plan does recommend a TOD Overlay District for a quarter mile radius around Girard Station:

Cambridge Lofts would still be illegal to build in our most ambitious TOD Overlay District unless the builder can find 7 parking spaces off-site to serve the otherwise-unusable industrial building.

The actual TOD Overlay regulations are not especially ambitious. The best practices are more nuanced than this (there is a whole Center for Transit-Oriented Development devoted to researching them), but the core elements of good TOD are simple: higher allowable density, mixed uses, frequent transit, and low parking availability in the walkable half mile area around transit stations.

Interestingly, a paper published last year in the Journal of the American Planning Association found that rail transit is one of the least important factors for successful TOD neighborhoods, and limited parking availability one of the most important. A neighborhood adjacent to a well-traveled bus line can achieve most of the benefits traditionally attributed to the presence of a rail station — reduced vehicle miles traveled, lower combined housing and transportation costs, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and more small business development — just by getting the zoning and parking policies right.

Our most ambitious TOD Overlay District – TOD-1 – caps building heights at 55 feet, and still has minimum parking requirements. It only halves the regular parking requirements, and you still have to supply “the lesser of what is required for the proposed use, or the number of accessory parking spaces in existence prior to the proposed use.”

Eyes on the Street editor Ashley Hahn has argued persuasively that Philly shouldn’t set parking minimums at all, so we probably really shouldn’t set them in an area we’re specifically targeting for lower vehicle miles.

The quarter-mile scope of the Overlay also seems a bit timid. Cambridge Lofts wouldn’t be included, even though it’s just .4 miles from Girard Station – a 9 minute walk. The Center for Transit-Oriented Development uses a half-mile radius to define TOD.

The bottom line is that there are no existing options under the code – even in the most ambitious TOD district – where a TOD-optimized project like Cambridge Lofts can be built legally.

3. Reform fatigue

The Nutter administration and City Council spent down a lot of political capital on modernizing Philadelphia’s code, and there does not appear to be much left over to promote transit-oriented development in the remapping.

A couple of areas where local civic and political leadership has been supportive (46th and Market, and the Regional Rail station at Temple) have been exploring proposals for TOD via the state TRID district program.

The Girard Station area recommended for a TOD overlay is overlapped by two City Council districts – Darrell Clarke’s 5th District and Mark Squilla’s 1st District – but neither have pushed an overlay during remapping.

Elections are coming up next year, and as the politics suggest, there’s little political upside in pushing a parking attrition policy in an area where two-thirds of the residents commute by car.

That doesn’t mean transit-oriented development doesn’t have any political juice. Urbanism, transportation, and related quality of life issues have been emerging as issues Democrats disagree about, and could figure prominently in the 2015 campaign next year. But it will probably take the campaign season to bring enough energy back into politics to get something as big as the citywide transit-oriented development overlay that Matt Ruben thinks is needed through City Council.

“”Legislation needs to be introduced by progressive members of City Council to make up for any deficiencies or strengthen any pro-transit elements of the code,” he said. “And one of the good things about the code is that it’s citywide. With zoning code reform there’s more of an opportunity than with some other issues for at-large Council people to get in on the act.”

Ruben thinks a citywide transit-oriented development overlay district stands a better chance politically than a local RCO-level or Council District-level overlay, because at-large Councilmembers and citywide non-profits and coalitions of voters can provide a counterweight to some of the more parochial interests.

“If you do it in one Council district, it’s going to be sponsored by the District Councilperson and you’re going to have a real fight on your hands in the district between people who want it and people who have concerns about the further elimination or reduction of parking requirements that it would produce in certain circumstances,” he said, “And that might be a battle worth having, but it would be a much more focused and pitched battle.”

He also pointed out that, as Northern Liberties will soon have an updated zoning map, in theory there should be many fewer variances, and thus fewer opportunities for community organizations to influence development policy using the variance process as a veto point. So until City Council members and the Planning Commission strengthen the transit-oriented development language in the code, lots of industrial buildings that “want” to become apartments will go wanting for adaptive reuse.

“It is stupid in 2014 for an old formerly industrial building that has great bones and is land-locked, for the city to require 14 parking spaces when there’s no place to put them,” Ruben said, “Is there a different use for this building you have in mind than what this guy is proposing, that will generate less demand for parking? Because the only other option – and there isn’t one – is to knock half or all of it down so you can build off-site parking. And then you’re faced with the same shitty design that we’re always struggling with.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.