The Penn Alexander effect: Is there any room left for low-income residents in University City?

It's in this corner of the city, where an array of forces have conspired to drive up real estate prices and, in some cases, drive out low-income renters.

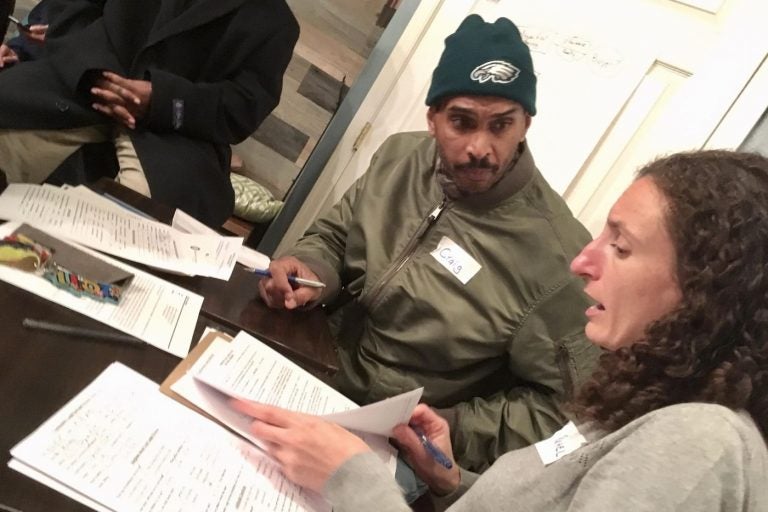

Rachel Garland, a lawyer with Community Legal Services, meets with Craig K. Lee, 53, who has lived at the Arvilla since 2011 and now will have to move. (Courtesy of Neighbors)

This story originally appeared on The Philadelphia Inquirer.

—

The 4500 block of Osage Avenue was quiet on a recent afternoon, except for the wind whipping through its stately tall trees, scattering leaves up the steps of fine Victorian houses and apartment buildings marketed to graduate students and faculty.

But there was a bit of commotion on the sidewalk, as Jay Tembo, 38, grappled with the news that he and other tenants would have to leave their home, a 1940, 16-unit apartment building with a name from another era: Arvilla.

“You need to call your caseworker,” his neighbor, Wanda Levan, 48, told him. The word was, everyone living there — the last apartment building on the block dedicated to affordable housing — has to move by the end of November.

Residents first received the lease-termination notices, then spotted a listing that advertises the property for $2.15 million, promising that, once renovated, the one- and two-bedroom units could command up to $1,400 a month, as the property falls “within the limited, highly sought after Penn Alexander School Catchment.”

It’s becoming a familiar story in this corner of the city, where an array of forces have conspired to drive up real estate prices and, in some cases, drive out low-income renters.

Those factors include appreciating values across what real estate observers call “greater Center City”; aggressive investments by the University of Pennsylvania, including creating home-buying programs for staff and backing the creation of the University City District; and, in 2002, the opening of the transformative school, a collaboration between the School District and Penn, which kicks in $1,330 a student, that has since been recognized as one of the best schools in the nation.

At the same time, two census tracts that cover parts of the catchment each lost more than 500 units of affordable housing from 2000 to 2014, according to an analysis published by the Federal Reserve. The median income in the area of the Arvilla increased 26 percent from 2006 to 2016. And as for home prices? They doubled in University City from 1998 to 2011 — but in the catchment, they tripled, adding a cool $100,000 or more to a property’s price tag. For instance, a 1,500-square-foot house on the same block as the Arvilla recently sold for $540,000.

Al Cyrus, who has lived in the Arvilla for more than 50 years, said it’s hard not to draw a connection. “When they put in that Penn Alexander building, it was a wonderful opportunity, but I didn’t know it was going to make all the real estate prices double over here. I didn’t know they were going to come for all the older buildings and try to make them condos.”

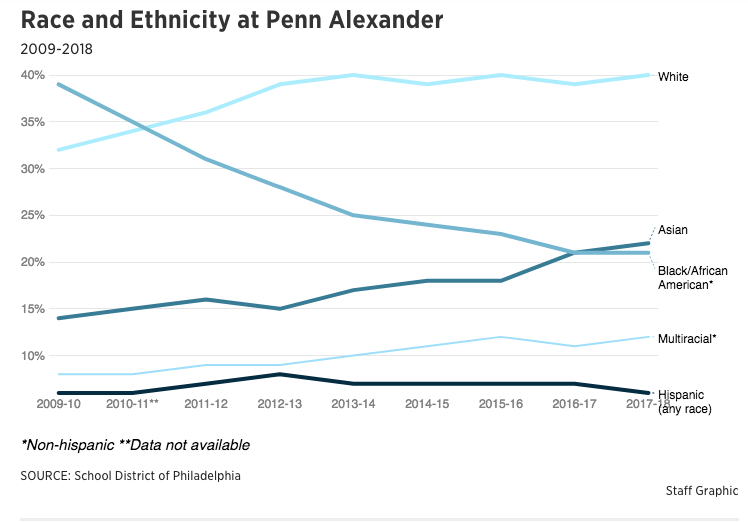

At Penn Alexander itself, the student body was 57 percent African American in its first year of operation. By the 2009-10 school year, that fell to 39 percent and, as of last school year, it was just 21 percent.

There are also fewer students classified as economically disadvantaged, meaning they qualify for free meals; the number fell 9 percentage points in five years, from 51 percent to 42 percent of the student body in 2017-18.

Emily Dowdall, policy director at the Reinvestment Fund, said these trends reflect complex and interlocking issues. Among them, “it brings up some of the tensions that come up a lot in the community development field, when a place-based investment becomes so successful that the lower-income households it has been intended to serve can no longer afford to live in the community.”

The landlord, the nonprofit Mission First Housing, says that it will help all the tenants relocate but that keeping the property just doesn’t make financial sense. The nonprofit houses 1,050 people with city Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) subsidies — 600 in its own properties, such as Arvilla, the rest through leases — but says that leasing is becoming more difficult as rental prices increase.

Mark Deitcher, director of the nonprofit’s business development, said that’s one reason Mission First is selling: It can reinvest the sales revenue from the 16-unit building into building a larger number of units that it will own, nearly 50 of them, farther out in West Philadelphia.

Besides, he said, the building is in disrepair, and the nonprofit isn’t in a position to fix it.

Three years ago, Mission First hatched a plan to bundle it with another project, at 46th and Spruce Streets, and obtain low-income-housing tax credits to fund both renovations. That fell apart after a nearby neighbor “threatened to sue us even if we got zoning, and keep us in court for years. We made the decision it wasn’t worth it to fight him.” Selling off both properties was the alternative.

“We really work hard to keep our affordable units in neighborhoods that are gentrifying,” Deitcher added. “We [own] close to 100 units in Center City. … But unless we already own something in these areas, it’s very hard.”

The building’s residents, and nearby neighbors, are not ready to accept that.

Some residents, such as Michael Jones, have been in the building more than a decade, and don’t want to leave.

“A lot of people here are like family to me,” he said.

On the other end of the spectrum, Seanika Gilyard, 31, said she just moved in six months ago with her three daughters, ages 13, 7, and 3. They’re finally settling into school, starting to make friends.

Tim Crawford, who’s lived there six years, said that, given the condition of the building, he wouldn’t mind leaving. It’s the way it’s being handled that upsets him: the notice, dated Oct. 18, to move by Nov. 30.

“I’m willing to move, but I feel like my rights are being violated. It’s inhumane,” he said.

On Monday night, a couple dozen residents and neighbors crammed into a West Philadelphia coffee shop to discuss what they could do to help: Ideas ranged from the pie-in-the-sky (find a buyer to keep the building affordable) to the pragmatic (exert political pressure, say, through district Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell). Some offered to lead fund-raising efforts to cover moving expenses, while others proposed letter-writing campaigns to push the owner to rethink the sale or at least give the residents more time. (On Thursday, Deitcher said Mission First will cover the moving expenses.)

J.J. Tiziou, who’s lived on this block for 12 years, organized the meeting after he spotted the real estate listing.

“That listing makes it all about the money that could be made, and not about the social investment that could be made in the community,” he said.

What’s equally disturbing to him is that it seems to fit a pattern: “Let the place crumble and then flip it — that’s a thing that happens in our city all too often.”

Just a few blocks away, at the deteriorating Admiral Court and Dorsett Court apartment buildings, dozens of low-income tenants were likewise told to leave this year ahead of a sale. The last remaining tenants were confronted recently with a posted notice ordering them out by Oct. 30.

Rachel Garland, a lawyer with Community Legal Services, is working with residents at both Admiral and Dorsett and at Arvilla. She said that as neighborhoods gentrify, there’s been an increase in mass evictions. Her question is: “What are we going to do to ensure these owners are doing it as a legal manner?”

And, beyond that, she thinks the city should weigh its commitment to keeping affordable housing in every neighborhood, rather than shunting it off to the most disadvantaged areas.

“Research shows that the more we concentrate poverty in particular neighborhoods, the less likely we are to break that cycle,” she said. “What are we as a city … going to do to prioritize keeping low-income housing in particular neighborhoods, sometimes on particular blocks?”

It raises the question: What was the priority guiding the development around Penn Alexander?

To Hannah Sassaman, a Penn Alexander parent who’s lived in the area since 1997, it was self-evident: University leaders “actively were trying to turn West Philadelphia into Cambridge.”

Barry Grossbach, who has been zoning chair of the Spruce Hill Civic Association “longer than you’ve been alive,” recalls how the neighborhood group began working with the university in the 1990s — even putting together a volunteer-run special services district that would become the precursor to the University City District.

“They worked with us on the establishment of a public school, they introduced a mortgage program to encourage their faculty and staff to buy in the neighborhood, they did work with us to stabilize the neighborhood — and that had a ripple effect for the communities farther west,” he said.

The plan had far-reaching consequences.

Among them, said Dowdall, was a shift in thinking as Philadelphians began to recognize that there is not a fixed number of “good” schools — and that to create more of them requires investment.

“It showed there is the ability for schools to improve — and the challenge is to proactively make sure they can still serve a diverse student body and that we can use all the policy tools we have available to maintain diversity in the neighborhood as well.”

Another consequence: Families determined to send kids to Penn Alexander are taking desperate measures.

Caleb Arnold and Carlos Munoz moved their family of four first into a one-bedroom apartment in the catchment, then found a two-bedroom space, all so their older son, who is autistic, could access supports they thought were not available at their old school.

“We stretched to be in that neighborhood,” Arnold said. “We live in a place that’s too small for us, and as our kids get bigger it gets increasingly too small. And we have no hope of being able to afford our neighborhood and one day buy a house — which is funny, because we’re both lawyers.”

The principal at Penn Alexander referred questions to the school district. Spokesperson Lee Whack said the district’s priority is creating great schools across the city. As far as a school’s impact on the community around it? “The school district does not control that,” he said. “Our focus is on educating young people.”

A Penn spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

But many Penn Alexander parents are growing keenly aware of the privilege of living within the catchment. Sassaman and others in 2016 formed a group called the Penn Alexander Equity Circle, that’s joined protests against the eviction at Dorsett and Admiral Courts, and advocated against removing a teacher from nearby Lea school as part of citywide leveling.

But there are larger forces at play. Sassaman’s is the last house on her block that has not been carved into student apartments, and offer letters from developers come in every other week.

For parents such as Gilyard, the mother of three being kicked out of Arvilla, there doesn’t seem to be much hope of staying in the catchment.

Still, she said, that neighbors reached out — that meant a lot. “It’s a great thing that the people from the block are being very supportive. I appreciate it. They didn’t have to call a community meeting, or even act concerned.”

A collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.