The local Black history hidden in Philadelphia’s school names

In this handful of names with city roots, there are stories long forgotten and glimpses of an overlooked past.

Listen 4:06

The exterior of Grover Washington Jr. Middle School in Olney. (Grover Washington Jr. Middle School)

Philadelphia’s school buildings are a tribute to its past.

That’s true of the structures themselves, some of which date back over a century.

But it’s also a nod to the people commemorated in the names of those school buildings. Those names — in ways big and small — help tell the city’s history.

The vast majority of public schools in the city are named after white men. (The school-namers of yore were partial to Union Civil War soldiers and former school board officials.)

Still, in a city that didn’t have a statue of a Black person on public land until 2017, school buildings are among the rare public spaces with any echo of Philadelphia’s Black history.

In this handful of names with city roots, there are stories long forgotten and glimpses of an overlooked past. And to mark the start of Black History Month, WHYY wanted to tell some of those stories.

Richard R. Wright Elementary

Take, for instance, Richard R. Wright Elementary in Strawberry Mansion.

No, the school is not named after the famed novelist Richard N. Wright, author of “Native Son” and “Black Boy.”

It’s named after a local trailblazer whose influence spanned states, sectors, and centuries.

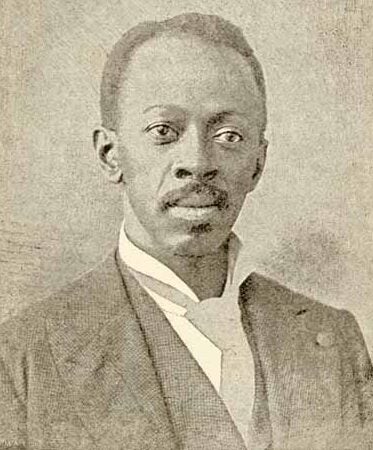

Richard R. Wright Sr. was born into slavery around 1855 and lived most of his life in Georgia. He was the highest-ranking Black officer during the Spanish-American War and founded the college that would go on to become Savannah State.

So why is he honored in Philadelphia?

According to the oral history project Goin’ North, which catalogs the Great Migration to Philadelphia, Wright left Georgia around 1920 after a teller at a bank called Citizens and Southern “insulted and then assaulted” his daughter. Wright joined his son in Philadelphia, where the pair quickly co-founded a bank, calling it, yes, Citizens and Southern.

Citizens and Southern became a vital institution in the local Black community, lending money to aspiring Black homeowners and entrepreneurs at a time when other banks charged exorbitant interest rates to Black borrowers. While other banks flopped, Citizens and Southern weathered the Great Depression.

And thanks in part to the bank’s early efforts, Philadelphia gained a reputation nationally as one of the rare places where Southern migrants could achieve homeownership, according to Janneken Smucker, historian at West Chester University.

“[In Philadelphia] homeownership was a big part of Black identity during that era,” Smucker said. “A bank like Citizens and Southern is so distinct in that it gives that capital and allows families to achieve this middle-class stability.”

Wright also had a pair of interesting connections to the world of Philadelphia education. His granddaughter, Ruth Wright Hayre, was the first full-time, Black high school teacher in Philadelphia’s public schools, the first Black high school principal, and the first Black superintendent.

Wright’s banking career in Philadelphia also came with a boost from Black educators. To get his new bank off the ground, Wright got money from the Negro Teachers Association, according to the book “Philadelphia: A 300-Year History.”

In essence, Black educators helped give this pioneering Black bank its start.

Hill-Freedman World Academy

Other schools in Philadelphia honor Black teachers directly.

Joseph E. Hill — partial namesake of Hill-Freedman World Academy in Northwest Philadelphia — spent years as a beloved instructor at Cheyney State Teachers College (later Cheyney University). Hill’s name was first attached to a school building in the Germantown neighborhood, built in 1844 for about $20,000, according to The Philadelphia Tribune.

The original Hill school was an all-Black school. Its graduates included Lulu Ballard, an early Black women’s tennis champion, and William T. Coleman, Jr., the second Black person to ever serve in the United States cabinet.

Hill’s name survived after the original building shuttered in 1961. But that almost wasn’t so.

In 1913, Philadelphia tried to rename the school after astronomist David Rittenhouse.

In an editorial, The Philadelphia Tribune called the attempt a clear sign of prejudice, noting that the school board had already erased Octavius Catto’s name from another school building.

“The Board of Education has been planning and shaping every means toward segregation and to have another strictly colored school robbed of its name just as was done with the O.V. Catto School means ‘war to the knife, and knife to the hilt,’” The Tribune wrote.

Penn Alexander

At the time of the naming controversy, Sadie Tanner Mossell was a 15-year-old high school student in Washington, D.C. — on the cusp of groundbreaking achievements.

In 1921, she earned a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Pennsylvania, becoming just the second Black woman in the U.S. to earn a doctoral degree (the first graduated a day prior) and the first African American to get a Ph.D. in economics. Six years later, she became the first Black woman to graduate from Penn’s law school and the first to pass the Pennsylvania Bar.

In the interim, Mossell married a fellow attorney, Raymond Pace Alexander. Working together, the couple forged pioneering legal careers. Raymond Alexander worked on an early school desegregation case in Chester County, won a seat on Philadelphia City Council, and became the first Black judge in Pennsylvania’s Court of Common Pleas.

Sadie Alexander became an assistant city solicitor, the first Black woman to achieve the position. She also served on the city’s Commission on Human Relations.

In 1998, the school district honored her legacy with the Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander University of Pennsylvania Partnership School, a West Philadelphia elementary school commonly known as Penn Alexander.

Ethel D. Allen School

North Philadelphia’s Ethel D. Allen School owes its name to a woman that “seemed indestructible,” as the “Baltimore Afro-American” once wrote.

Born in North Philadelphia, Dr. Ethel Allen became an osteopathic physician, community leader, and Republican politician. She became the first Black woman on Philadelphia’s City Council in 1972 and later served as secretary of the commonwealth under Gov. Dick Thornburgh.

Standing a shade under five feet, Allen was known for her rambunctious spirit and was the local civil rights voice that “power brokers could accept,” The Philadelphia Tribune wrote. It was a voice, the paper said, that stood out from the crowd:

“Forever City Hall will have to acknowledge that one little Black girl from North Philadelphia made it to the hallowed halls to make herself heard.”

Laura Wheeler Waring School

Laura Wheeler Waring had a long career as a portrait artist and art teacher at Cheyney State. Her husband, Walter Waring, was a teacher in the School District of Philadelphia.

As a prominent Harlem Renaissance artist, her portraits hung in the Corcoran Gallery, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the Brooklyn Museum, and attracted the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt. She became “one of the most widely known Negro artists in the United States” according to a 1946 article in The Philadelphia Tribune, and her works included a portrait of another Philly school namesake, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.

After her death, the Laura Wheeler Waring School just north of Center City was named in her honor.

Others with national profiles, connections to abolition

The list of prominent Black people honored on school buildings includes some with national profiles and local connections.

Paul Robeson, namesake of Paul Robeson High School for Human Services in West Philadelphia, was a world-famous athlete, actor, singer, and activist before he quietly retired and moved to Philadelphia. Famed saxophonist Grover Washington Jr. lived most of his adult life in the city, and was honored shortly after his death with the naming of Grover Washington Jr. Middle School in Olney.

Astronaut Guion Bluford holds the distinction of being the only living Black person to have a school named in his honor. And it’s the West Philadelphia elementary school he attended, which was once named after former judge William B. Hanna and subsequently became Guion S. Bluford Elementary in 1994. The Bluford school is now run by the Universal charter network.

There are also traces of the city’s Black history in the names of white people honored on Philadelphia school buildings.

Jay Cooke, financier and namesake of Jay Cooke Elementary in North Philadelphia, helped establish Camp William Penn, the only training ground exclusively for Black troops during the Civil War. The camp’s commander, General Louis Wagner, got his own school, Wagner Middle School in West Oak Lane.

Given Pennsylvania’s prominent role in the anti-slavery movement — and the glut of Civil War-era figures honored with school names in Philadelphia — there are other namesakes with abolitionist connections. William D. Kelley, John Hartranft, Henry Lea, Alexander McClure, and Roberts Vaux all had varying connections to the abolitionist movement.

So, too, did poet and school namesake James Lowell, who moved to Philadelphia to edit an anti-slavery newspaper. But Lowell’s stance against slavery did not preclude him from being prejudiced. He supported Black suffrage, according to a biographer, but in part, because he felt the “intellectual and traditional superiority” of white people would ensure their political dominance.

And famed nineteenth-century Philadelphia actor Edwin Forrest, for whom Edwin Forrest School in Mayfair is named, broke into the profession by performing in blackface. In a heartening historical twist, Forrest’s North Broad mansion eventually became the Freedom Theater, a cornerstone of the city’s Black theater scene.

In Philadelphia and elsewhere, there’s recurring pressure to rename schools whose namesakes have racist, sexist, or otherwise infamous pasts. San Francisco made news by recently changing the name of 44 schools. And there was an effort last year in Philadelphia to remove names such as Andrew Jackson, Woodrow Wilson, and General Philip Sheridan from schools. The group attempting to rename Andrew Jackson School wants to instead honor Fanny Jackson Coppin, a pioneering Black educator who lived in South Philadelphia and is the namesake of Baltimore’s Coppin State University.

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.