The history of electronic music is inside a warehouse in Harleysville, Pa.

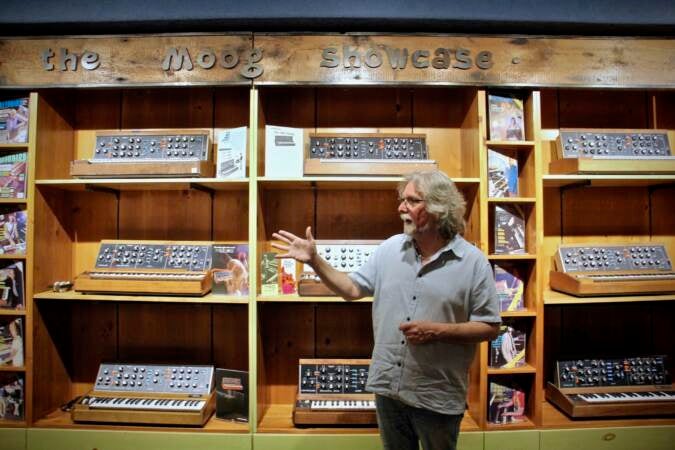

A collector of a massive collection of synthesizers and vintage rock gear in Harleysville, Pa., wants to tell the story of rock and roll, one Moog at a time.

Listen 4:09An unassuming warehouse off Route 63 in Harleysville contains one of the world’s largest collections of vintage electronic music gear, crammed with amps, synthesizers, guitar pedals, mixing boards, and sundry electronic eccentricities.

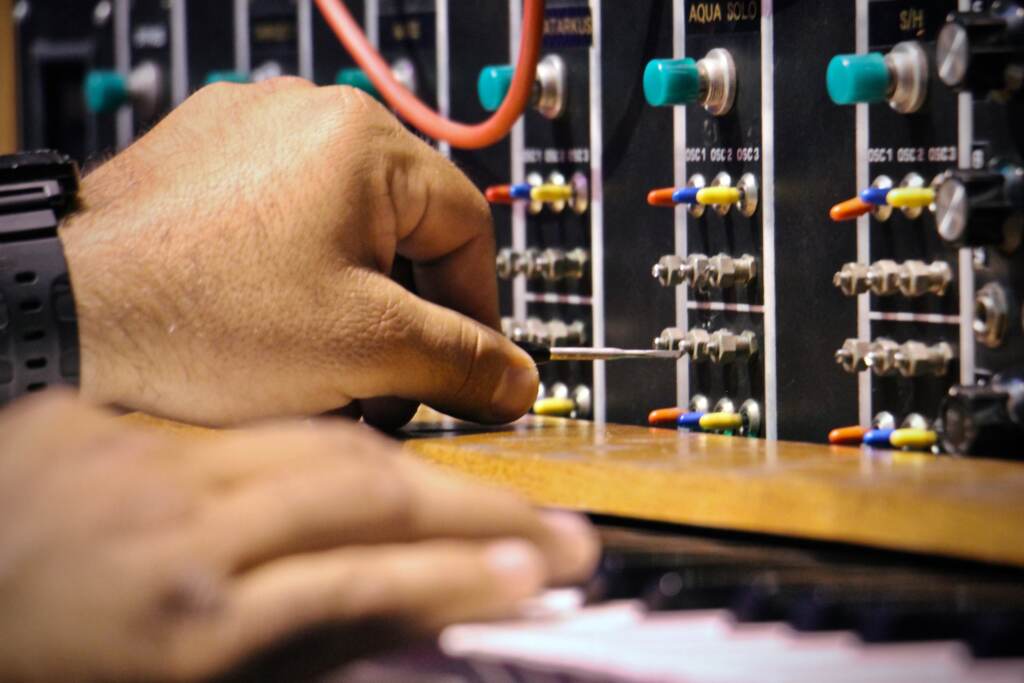

The collection is rich in analog electronics used during the classic 1960s and ’70s era of rock and roll, but it spans from the early genesis of synthesizers in the 1930s to the late 1980s, when the market began to be dominated by digital keyboards and computer software.

This is the Electronic Music Education and Preservation Project, or EMEAPP. By design, there is not a computer anywhere in the building, aside from a few rare digital prototypes from the early 1980s.

“The general energy of the world tends these days toward a homogenizing energy,” said Wouter De Backer, also known as the musician Gotye, who sits on EMEAPP’s advisory board. “There’s been all these fantastic things that have come from the democratization and miniaturization and economization of electronics, but over the years that has made us blind to the fact that there’s this homogenizing pull.”

De Backer disrupted that perceived homogenization of pop music in his hit 2011 song, “Somebody That I Used To Know,” by using a xylophone to carry the melody, with a sample from a 1967 Latin jazz nylon-string guitar mixed with an African drum.

Vintage analog synthesizers, often cast into the dustbin of musical history, have what he calls “dormant potential.”

“I felt over the years that instruments that are more untapped, that still have a dormant potential, have so much possibility for adding to the richness and diversity of a culture,” De Backer said.

EMEAPP has 30,000 square feet of dormant potential. The former wholesale food warehouse in Montgomery County is stacked floor-to-ceiling with old technology. Each piece tells a story.

“Here’s a Sennheiser Vocoder that belonged to Kraftwerk,” said executive director Drew Raison, gesturing to a rack-mounted box with 50 knobs and about 30 cable ports.

Nearby is a cluster of electric organs. “That Hammond B-3 used to belong to John Entwhistle of The Who,” he said.

Around the corner is the organ Rick Wakeman of the band Yes used to record the hit song, “Roundabout,” and the Marshall amp Lindsay Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac used to record the album, “Rumours.” Around another corner is the amp system Led Zeppelin used on its 1969 American tour, and the portable mixing board Neil Young likely used to record “The Needle and the Damage Done” for his 1972 album, “Harvest.”

“That’s the wah-wah Jimi Hendrix used at Woodstock,” said Raison, pointing to a guitar pedal on a high shelf. “I’m going to say that again: That’s the pedal Jimi Hendrix used at Woodstock.”

Raison cannot give a number to the amount of gear in EMEAPP’s collection. His best guess is 2,000 or 3,000 objects, including early Ondioline electronic synthesizers from the 1940s, and one of the world’s first digital synthesizers, the Con Brio ADS 100 used to make the soundtrack for “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Kahn” in 1982.

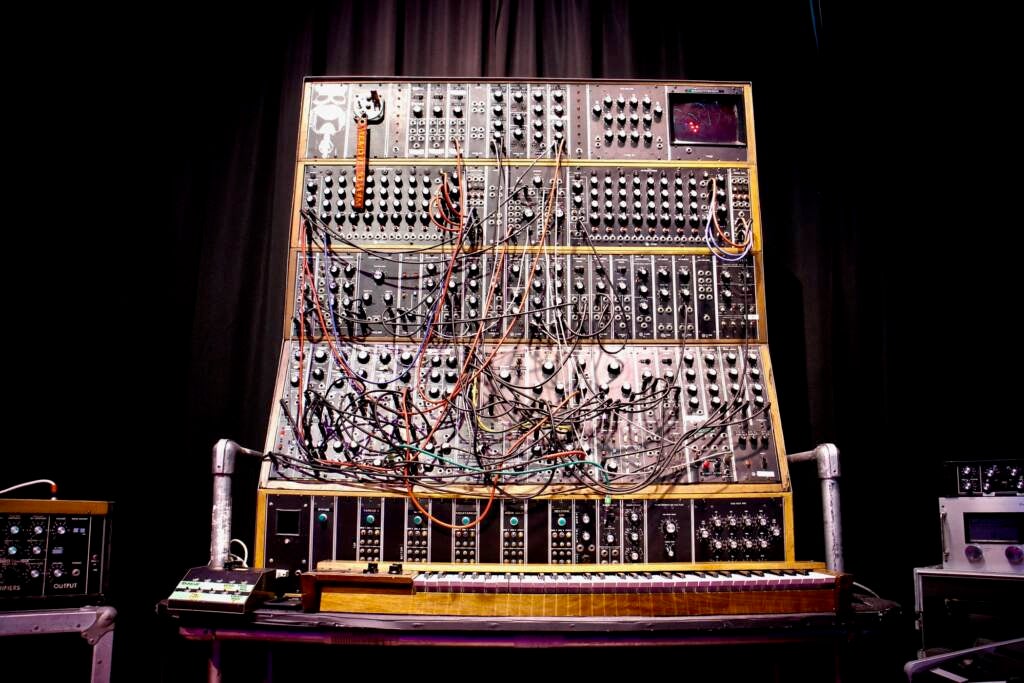

The pièce de résistance is the enormous Moog system that Keith Emerson hauled around the world several times while touring with Emerson, Lake and Palmer from the 1970s through the 2000s.

“You’re looking at the Keith Emerson world here,” Raison said of the recording studio built inside the warehouse.

The centerpiece is Emerson’s monolithic Moog, standing about 10 feet high with a dizzying number of knobs and patching cables. Next to it is a smaller Hammond L100 organ Emerson liked to abuse on stage. It has two daggers stuck into the keyboard, its wooden body repaired with steel mending plates.

Emerson, a rock showman, would sometimes stab the keys with daggers to hold them down while he moved to another keyboard. He destroyed a lot of L100s over his career. This particular L100 caught fire onstage during a show in Boston in 1997.

“Basically, the L100 is your grandmother’s organ from the living room, and he beat the living daylights out of them,” explained Raison. “Keith ate the L100 for dinner. He would throw them around the stage, pull it on top of himself, play upside down, stand on top of it, and rock it.”

EMEAPP started four years ago as the nonprofit foundation stewarding the collection that its founder, Vince Pupillo, has been amassing for 20 years. The organization keeps the equipment in working condition as much as possible and uses them for educational programs, including group tours and the occasional loan to an exhibition. Some pieces were recently part of “Play It Loud,” a 2019 exhibition of rock gear by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Pupillo started collecting the pieces because these were the kinds of instruments he played as a young musician in the 1960s and ’70s.

“When I was in high school and in college, I always had a band and I always played,” Pupillo said. “But when disco came along, it took the joy away from playing rock and roll.”

He quit playing around 1978, and sold his Minimoog, his Fender Rhodes keyboard, and his Hohner clavinet, to focus on raising a family and building a company. He eventually became successful in the salad business.

Around 2002, Pupillo wanted to get his hands on those old instruments again, with their “warmer” tones.

“Every time I hear those instruments, it just makes you feel like butter,” he said.

Once he had the keyboards from his youth back in hand, Pupillo started acquiring more as his interest in the history of the technology deepened.

Pupillo became known to collectors and musicians as the guy who would buy instruments that otherwise might be thrown away. Around 2016, he was approached by the Audities Foundation, a Calgary-based vintage recording studio, to see if he would be interested in five Minimoog prototypes, the handmade portable synthesizers Robert Moog’s company made while developing the product for the retail market. The Minimoog became the first synthesizer an average musician could buy off the shelf, revolutionizing electronic music.

Pupillo thinks that the Minimoog was essential to the development of popular electronic music, and that these prototypes, as the objects on which concepts of analog sound technology were being worked out, had huge historical importance.

EMEAPP was created in 2017 as a mission-driven nonprofit to preserve and maintain the invention, engineering, and culture of early electronic equipment, and tell the stories behind the gear.

“I did whatever I had to do to get those instruments under one roof and preserved,” said Pupillo. “A lot of musicians and folks in the music industry, they want to preserve their legacy, and they see what we’re doing.”

De Backer/Gotye saw that EMEAPP coincided with his personal interest in antique electronics. In 2015, he started a partnership with the pioneering electronic musician Jean-Jacques Perrey, who in the 1950s was a virtuoso of the Ondioline, an early synthesizer that allowed the players to create vibrato on the keyboard.

“It had this incredibly boisterous, hyperactive, almost kind of infectious joy about it,” said De Backer. “Other parts of his music have a real romanticism, a wistfulness about them, and he manages to coax those poles of expression out of the Ondioline.”

De Backer had organized an Ondioline ensemble and planned a concert in New York with Perrey. However, Perrey died at age 87 in Switzerland before that performance could happen. De Backer started a label, Forgotten Futures, to reissue Perrey’s electronic Ondioline recordings from six decades earlier.

“There are really wonderful, human stories behind those instruments,” said De Backer. “They’re often so surprising and unlikely that they feel like an antidote to what feels like the same narratives we hear again and again in the culture.”

The pandemic hit EMEAPP hard, immediately canceling all school tours and events around the collection. Nevertheless, it is still acquiring and maintaining equipment. Recently, it received a grant to finish construction of a new control room for its recording studio, which will allow musicians to tease fresh sounds out of the old equipment.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.