‘Thank you to the kids’: Virtual African American Children’s Book Fair attracts guests from around the world

An online audience that included people from Botswana and Albania heard authors and illustrators talk about their work at the Philly-based event.

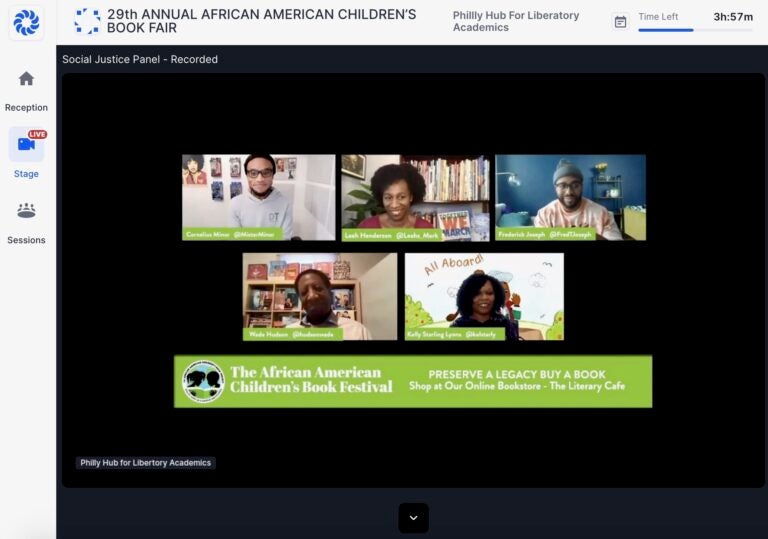

Authors exchange ideas during the social justice panel at the 29th annual African American Children's Book Fair. (Hopin screenshot)

Guests logged into the 29th annual African American Children’s Book Fair Saturday from across the country — and even as far away as Botswana and Albania — to get a closer, if virtual, look at some of the books on display. But more specifically, they wanted to see the authors and illustrators who created them.

The book fair is one of the largest and oldest events dedicated to Black children’s literature in the United States. This year, its nonprofit organizer chose to shift the event to the virtual platform Hopin.

“Rain, icy temperatures, sleet, and even hail has not deterred the African American Children’s Book Project from hosting this annual event held for over 29 years in Philadelphia during Black History Month,” said Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati, literary consultant and creator of the event. “So, why would a pandemic?”

The Philly Hub for Liberatory Academics, a group of local public school educators seeking to provide resources and accessibility to students and community members, also helped guide users on the platform.

After a brief reception, those attending watched a series of panels — both live and prerecorded — touching on topics from social justice and love, to things like artistry and fantasy. In addition, there were prerecorded interviews with members of the Pinkney family, all of whom seem to have a knack for literature and illustration.

On the artistry panel, illustrators engaged in a compassionate discussion about the techniques with which they draw and how those relate to creating lively Black characters on paper.

Gordon C. James explained that he doesn’t use any browns when painting Black characters. Instead, he mixes and blends the vibrant undertones that make up someone’s skin color. This can be as simple as mixing reds and purples to finding ways to incorporate “seafoam green.”

“That is just technically what I’m thinking about when trying to get that full spectrum of color that is in our skin, no matter what, no matter how light or dark we are. It’s just always so many colors in the skin, and that is very fun for me to try to get,” James said.

During the culture and social justice panels, authors sought to define what Black children’s books are in this moment.

Cozbi A. Cabrera, an author and illustrator of several award-winning children’s books, pointed out the distinction between culture and race.

“It’s incumbent upon us to sort of know the details of each other, and to find those sort of universal chords and also sort of appreciate those sort of varying details and distinctions that make us so amazing,” Cabrera said.

Tracy Deonn participated on the fantasy panel. Her most recent novel, “Legendborn,” is her debut book in the world of young adult fantasy, and she wanted children and parents alike to take away an important lesson from the genre.

“Fantasy is not just about escapism. It’s also about having access to different parts of the community and culture,” Deonn said.

Because the book fair was a virtual experience, those attending were limited to offering their reactions to the panelists in chat rooms, which were lively throughout the event.

“I’m supposed to be working! I’ve barely been able to leave this seat. Now that I know what’s missing, I will make this a priority every year,” one wrote.

“Excited to be in the presence of such amazing writers and illustrators,” another said.

“Yes, awesome thought-provoking questions. I’m in tears. This discussion is so good,” a third person wrote.

Overall, book enthusiasts seemed to take a lot away from the fair.

“I am enjoying the varied and very informational discussions,” said Andrea Malenya, director of the Botswana Book Project, a nonprofit dedicated to increasing literacy and access to books in the sub-Saharan country.

Kayla Hoskinson, a librarian for the Free Library of Philadelphia, said the book fair allows her to better tailor children’s literature to fit the community that she serves.

“It helps me be more intentional in my role as a children’s librarian,” Hoskinson said. That’s true not only for the books she orders for her library, she added, but also the ones she orders for her personal collection “and the books that I choose to share out to patrons and lift up.”

“In order to do that in this city,” Hoskinson said, “it’s really important to be listening to voices of Black writers.”

For authors and illustrators, the book fair has long been an opportunity to reach an audience they were wrongly told doesn’t exist.

“All my life, I’ve been told, even by publishers, that Black people don’t buy books. And then here comes Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati with the African American Children’s Book Fair, and there is a line around the block and these are people that just want to get books. These are Black people that want books. And suddenly, you realize that you’ve been told a lie for most of your life. It’s the reason why I keep coming back year after year,” said Eric Velasquez, an author-illustrator who spoke on the culture panel.

Velasquez has been in the business for more than 30 years and has been participating in the event for almost as long.

“Whenever Vanesse Lloyd-Sgambati calls or puts out the call, I come,” Velasquez said. “No matter what.”

Near the end of the social justice panel, the authors took the opportunity to thank another important party.

“I want to say thank you to the kids for inspiring us,” said author Kelly Starling Lyons. “For helping us to create stories that we hope will let you know how much you matter. And that within each of you is a storyteller, so read our stories, but also remember that you have a voice.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.