Shofuso digging for its Centennial ancestor

Kim Andrews is standing on a busted up paved path, pointing at a patch of tamed weeds and poison ivy in West Fairmount Park. We are looking for the past.

We are facing the site of the first Japanese garden in America, which was part of the Centennial Exposition in 1876, just uphill from Shofuso, Fairmount Park’s more recent Japanese House and Garden.

The exposition garden is long gone but Andrews, executive director of the Friends of the Japanese House and Garden, is showing me where archaeologists from AECOM Burlington will begin to dig on Wednesday in search of any fragments left behind from the garden and Japanese Bazaar building that were once here.

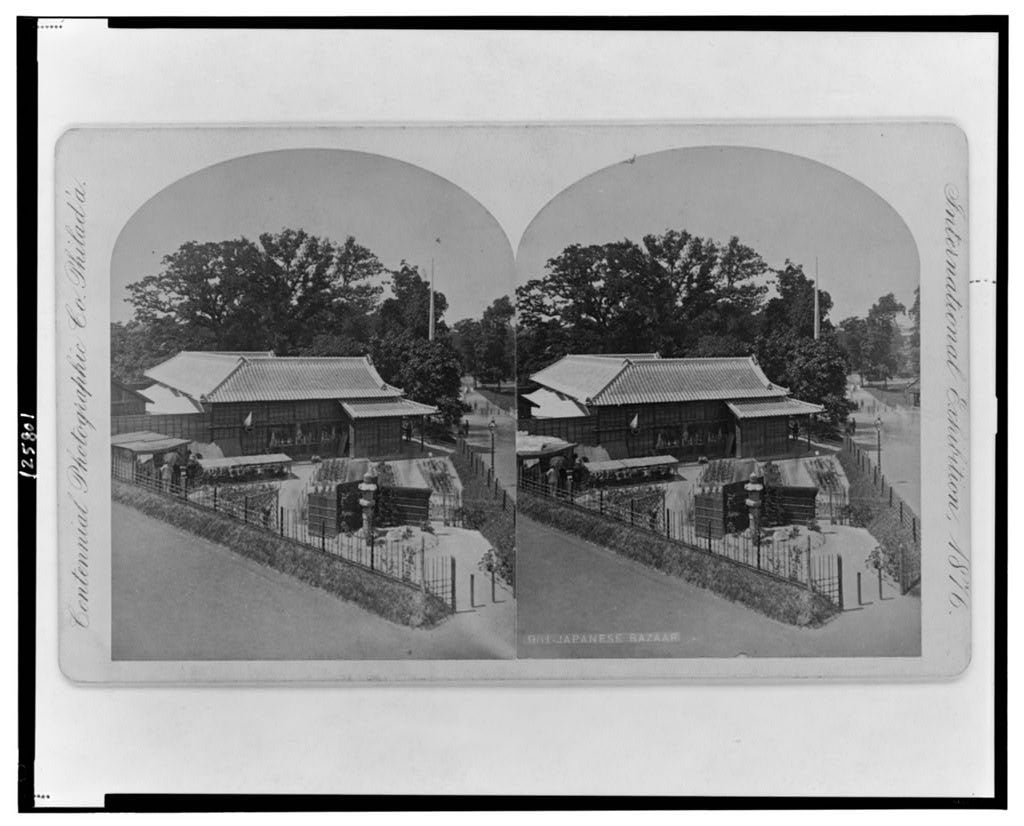

Visitors to the Centennial Exposition who stood in this spot would have seen a garden and U-shaped Japanese structure (seen in the stereograph above), a retail bazaar of Japanese garden implements, pottery and souvenirs.

“Japan intended to make a splash, and they did,” Andrews said of the two buildings Japan created for the exposition, which showcased traditional design aesthetics and construction techniques that were new to western audiences. At the time Japan was just opening up to the west, and Japan’s presence at the exposition was intended as a means of cultural exchange.

Today the site is a woodsy hinterland between Memorial Hall, Shofuso, and Carousel House. Little pink and yellow landscape flags currently pepper the ground, marking areas of archaeological interest identified using ground-penetrating radar. As archaeologists dig, from this week through mid-August, the hope is their explorations will reveal more about the precise location of historic paths, plantings, and buildings from the exposition.

If the dig is revealing it will meaningfully inform a new master plan for Shofuso that is being developed and, like the dig, made possible through funding by the William Penn Foundation. A goal of the master plan, Andrews said, is to creatively interpret the site of the 1876 garden and bazaar, perhaps through the creation of an interactive play space for children. The plan will also likely float the idea of a new visitors center for both Shofuso and the Centennial District at large up toward Belmont Avenue.

By activating this underused section of parkland the hope is to help draw visitors to Shofuso, link it with other very nearby attractions like the Please Touch Museum at Memorial Hall, and connect more deliberately with the Parkside neighborhood.

Though Shofuso is a park site owned by the city, the nonprofit Friends of the Japanese House and Garden has managed the house and gardens since the 1980s. What was long a lean operation has expanded significantly in recent years. Since 2010 the number of annual visitors to Shofuso has tripled, and its staffing and budget have grown in step.

For the Friends of the Japanese House and Garden the dig and master present a major opportunity to tell a much bigger story about the succession of Japanese cultural landscapes in this part of the park, spanning more than a century.

When the Centennial Exposition was over, the Japanese Bazaar site was removed. But in the years following the exposition a Japanese-influenced lotus pond and garden were created just 250 feet downhill from the earlier Japanese site. Then in 1905 a Japanese Buddhist temple gate was installed at the pond, purchased as a gift to the city when the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis closed. During a 1955 restoration campaign for the historic temple gate, it was lost to fire. Just three years later Shofuso as we know it was installed at the pond after being on display at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the gardens further refined.

All three events – the 1876 and 1904 expositions and the MoMA exhibit – were efforts to bolster friendship and exchange between Japan and America and the choice of Philadelphia was deliberate.

Besides the pond and paths there are few physical remains that clearly connect these different eras of Japanese landscapes in Fairmount Park. There is one that Andrews points out to me in an historic image of the exposition’s Japanese Bazaar – a little stone lantern. Today it’s tucked off a path a few hundred feet away in Lansdowne Glen but Andrews is hopeful about moving it back to its original site uphill. After it’s conserved and reinstalled, the lantern could be used as historic marker that illuminates a new interpretation of history and orients the visitor experience at the exposition site.

For now, standing in that no-mans-land uphill from Shofuso means looking at a lost landscape. But as Andrews and I pore over historic maps and images we’re simultaneously looking at what came before.

“You’re looking through time,” Andrews says. “It’s kind of a Zen moment when you can see what was there.”

Andrews hopes a new interpretation of this site can create more of these transportive moments, at a new hub of activity where past and present can coexist.

Shofuso is hosting a public archaeology day on Saturday, August 1 from 11am-5pm. Visitors can see the archaeologists at work and ask questions about the project. The dig site is near where Horticultural and Lansdowne drives meet, just uphill from Shofuso.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.