See and search: six decades of Pennsylvania population shifts

Click through the slide show above to see the shifts over time. Or zoom and search for a municipality to find its population in a given decade using the interactive maps below.

The latest U.S. Census numbers show Pennsylvanians are gravitating back toward cities — but that’s after decades of dispersion and clustering in new, smaller population centers.

Keystone Crossroads pulled the numbers and created a series of maps showing the Commonwealth’s population distribution for each U.S. Census starting in 1960, plus the most recent municipal-level numbers for 2014 released recently.

Barry Denk, who heads the Center for Rural Pennsylvania, stressed that “one size doesn’t fit all” when it comes to explaining demographic shifts and what they signify about, or for, communities.

Centralia comes to mind. The city’s hollowing out had less to do with wider economic trends than it did an underground mine fire that made the town uninhabitable.

We didn’t get into that level of detail for this initial report. But below each map, we give some context to populations changes from decade to decade by highlighting some broader socioeconomic trends.

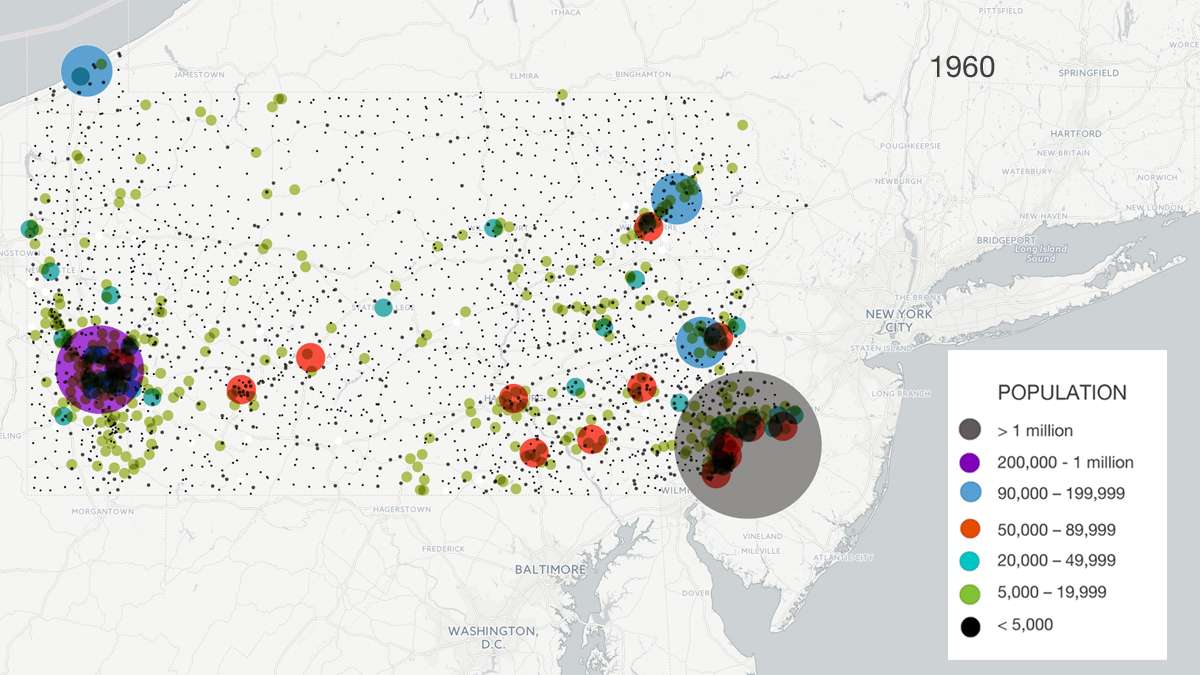

1960

More than half of Pennsylvania’s population lived in 140 municipalities in 1960. It’s now half living in more than 200, according to Keystone Crossroads’ analysis of Census data.

The population rose by more than 1 million people during that time. But the gains concentrated in townships, while the Commonwealth’s three dozen largest cities lost more than 1.2 million residents.

Suburban flight and sprawl have been national trends, but Pennsylvania is an outlier in some ways.

Philadelphia’s population dropped by more than 400,000 residents, the steepest national decline aside from Detroit and two New York City boroughs, according to University of Washington professor Richard Morrill’s analysis published by New Geography just after the last Census.

Most of the country’s non-metro counties, however, experienced steady growth — a trend that’s not reflected, or at least is less pronounced or consistent, in Pennsylvania.

The non-metro areas that lost people during the past 50 years did so at some of the most dramatic rates in the country, attributable to the collapse of the mining industry (as in West Virginia and Kentucky), Morrill says.

But what about in the meantime?

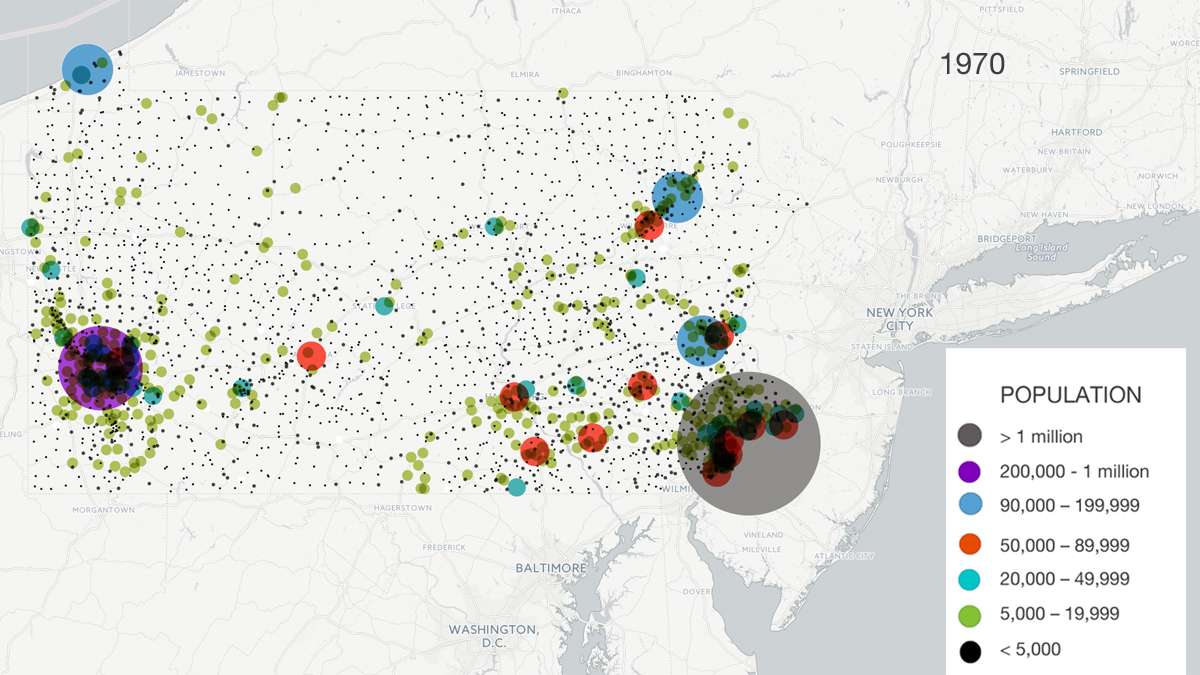

1970

This is when suburban flight starts showing up in the statistics for Pennsylvania, and nationally.

New roads and highways help facilitate the move away from urban cores, allowing people to conveniently get to work from the suburbs.

Housing stock has been increasing since after World War II. By 1975, the Commonwealth’s number of available units has quadrupled, according to Harrisburg-based Tri-County Regional Planning Commission.

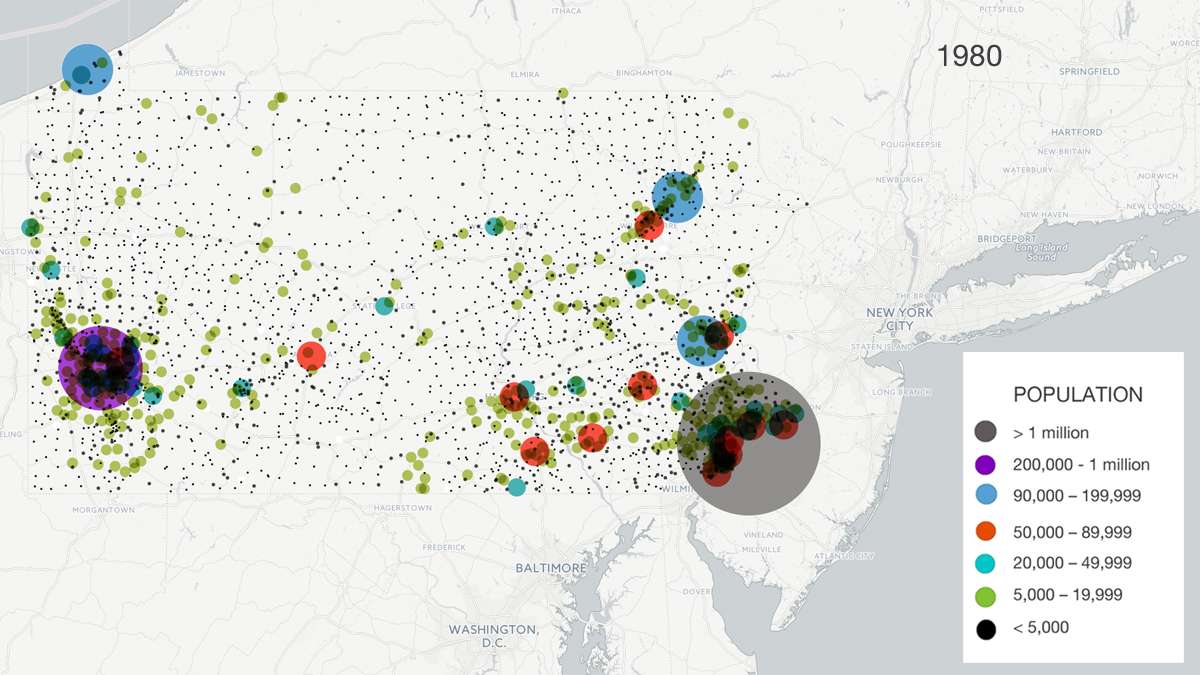

1980

The 1980 Census shows the beginning of what would be long-term trends: population declines in Western Pennsylvania and increases in the eastern counties. Each region’s respective trend is more pronounced in the south, Denk says.

The loss of steel, coal and textile industry also prompted people to start to move away from the southwestern corner of the state, in particular, Denk says.

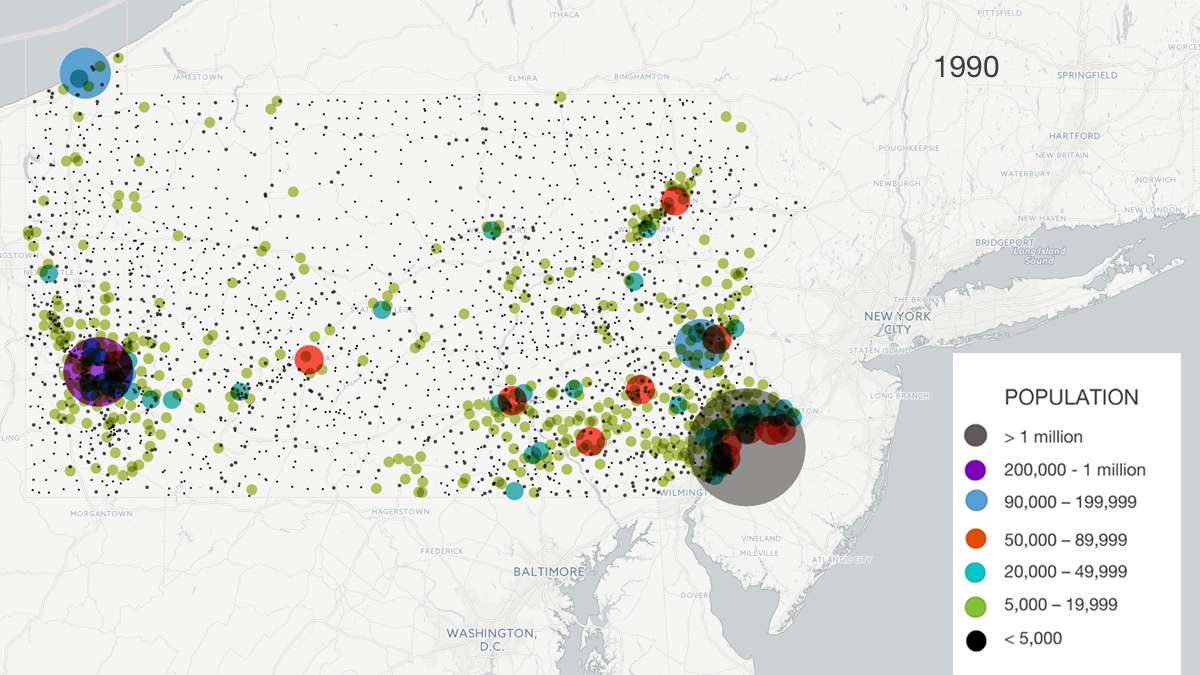

1990

Economic globalization helps some U.S. cities to rebound or stabilize after struggling for years with suburban flight and deindustrialization.

Philly and Pittsburgh’s loss rates slowed during the 80s — but neither city’s had a Census-documented gain yet.

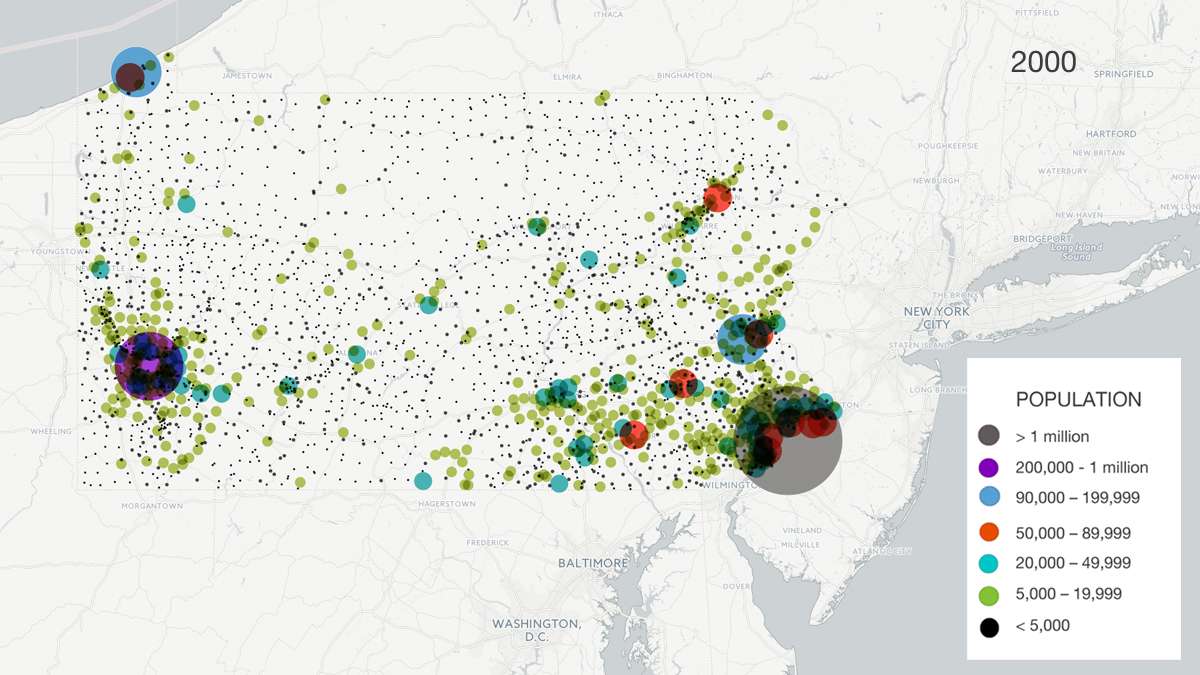

2000

Northeast Pennsylvania is growing. The change is happening in its Pocono region, not urban cores.

That’s attributable to an influx of former residents of nearby New York City, according to Penn State Professor of Public Policy and Administration Beverly Cigler.

Primarily, they were retirees. Or people still working, but established enough in their careers that they didn’t have to be physically present in their workplace as frequently, Cigler says.

But the potential for that population flow always existed. So why did it become a trend starting during the 1990s?

Was it that during that time, Internet and cell phone use became more widespread, enabling telecommuting?

Cigler says no.

“We like to talk about that, but it’s less of a factor than implied,” she says.

But Denk says technology probably was a factor, citing documentation of similar effects in other areas including Washington, DC.

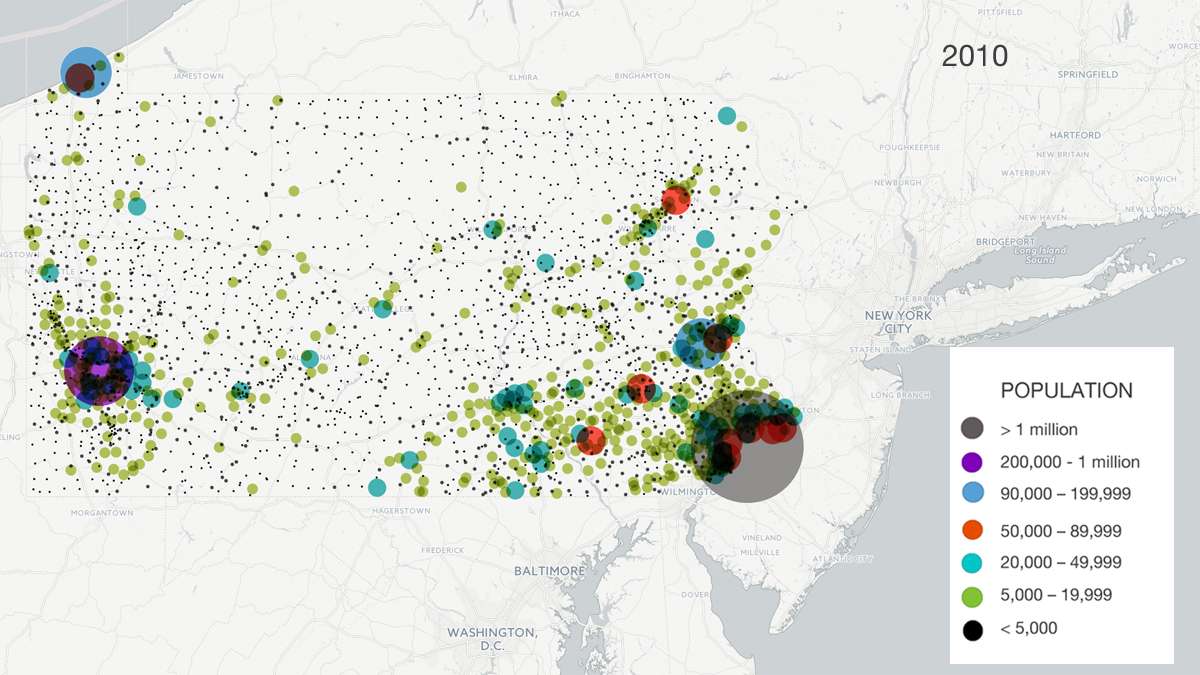

2010

Influx of New York retirees and mid-career professionals continues in Northeastern Pennsylvania, increased and expanded to include others in the wake of the Sept. 11th attacks, Cigler says.

Shale regions elsewhere in the United States post more dramatic population gains from the industry’s boom than in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale region, according to John Cromartie, an analyst USDA’s Economic Research Service.

The effects are less dramatic, perhaps, because people already were living in proximity of job sites, while other U.S. fracking hotbeds located in more remote regions require workers to move nearby from elsewhere.

Also, some Pennsylvania’s Shale-region residents moved after selling their land to natural gas companies, Cromartie suggests.

A report from the Center for Rural Pennsylvania found that growth wasn’t uniform, and that shale-related growth didn’t counter longer-term population losses in rural Pennsylvania.

Some areas already losing population began to do so more rapidly since the boom began, the report found.

Denk points out that some areas became “mini corporate hubs” that attracted employees who ended up buying houses and staying in the area. That’s where the growth appeared, Denk says.

What didn’t change: rural out-migration linked with death rates that exceed birth rates, he says.

Although boroughs keep losing people, the state’s cities are gaining overall (if not everywhere), according to the Penn State Data Center’s analysis of the most recently updated Census numbers.

Both types of communities are built out, but Cigler attributes certain cities’ ability to start attracting people again to more fruitful revitalization efforts (not to mention jobs and amenities).

Suburban townships, though, still account for the vast majority of population increases where there’s available land yet the areas are developed enough to have infrastructure and enough amenities, Cigler says.

And Denk says Pennsylvania’s rural townships also might be retaining or re-attracting people due to family considerations such as caring for aging parents. Cromartie finds that to be true nationally.

Denk also referenced the Center’s longitudinal study on rural youth. Participants not only reported a desire to move away to advance their education and careers, but also to return, ultimately, to raise their families, for a better quality of life, open space, sense of place and other attributes.

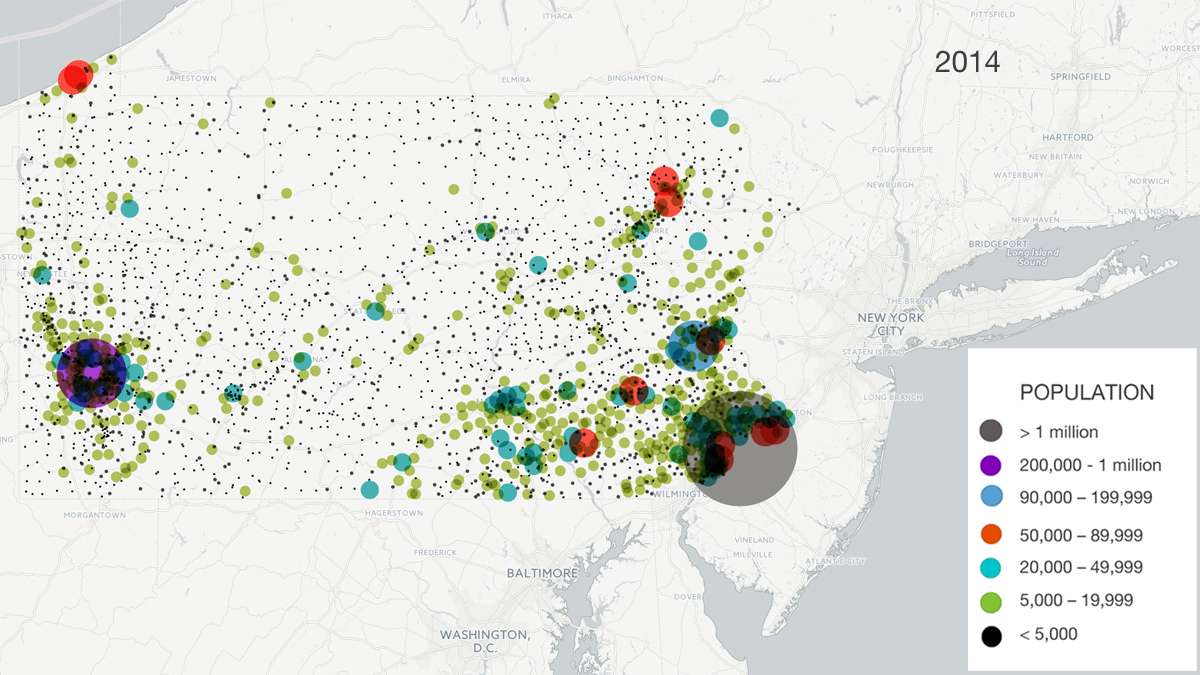

2014

Although boroughs keep losing people, the state’s cities are gaining overall (if not everywhere), according to the Penn State Data Center’s recent analysis of updated Census figures.

Both types of communities are built out, but Cigler attributes certain cities’ ability to start attracting people again to more fruitful revitalization efforts (not to mention jobs and amenities).

Townships, though, still account for the vast majority of population increases.

The suburban types still have land available for development and expansion.

Denk says family considerations – such as caring for aging parents – might prompt people to remain in, or return to, Pennsylvania’s rural areas. Cromartie found that to be true nationally as well.

Denk also referenced the Center’s longitudinal study on rural youth. Participants not only reported a desire to move away to advance their education and careers, but also to return, ultimately, to raise their families for the quality of life, open space, sense of place and other benefits afforded by the area.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.