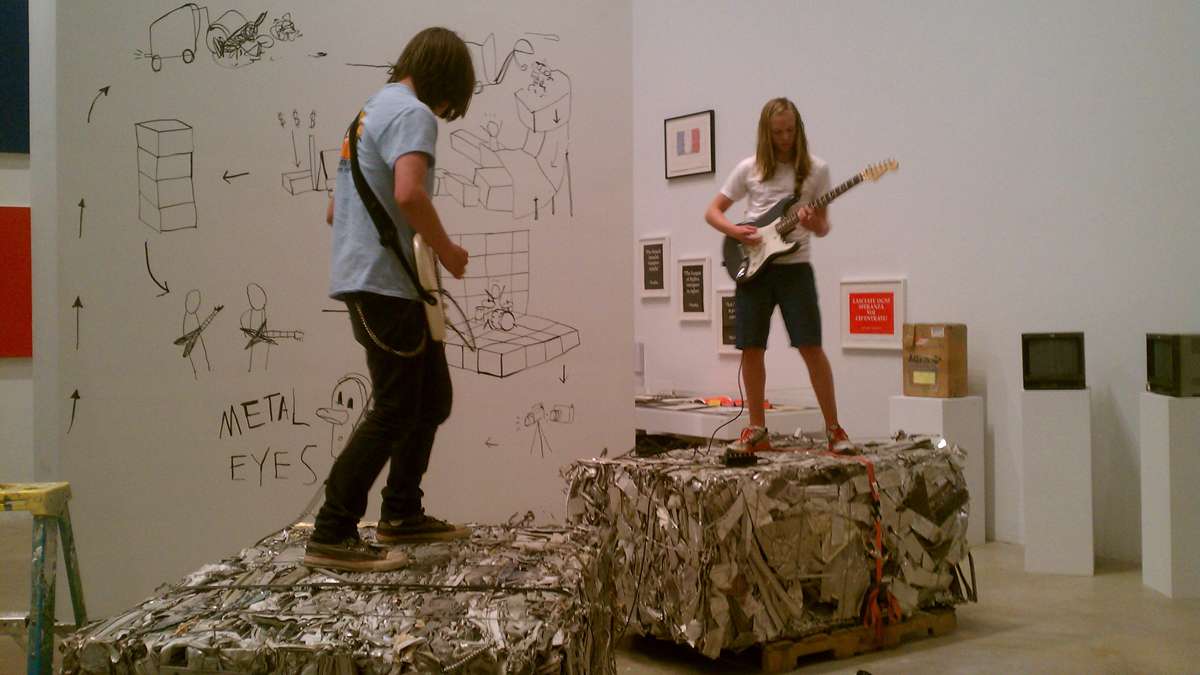

Scraps of metal, sounds of Metal Eyes combine in ‘waste music’ installation

ListenAt a current intallation at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, two guys will be standing on these bales of shredded metal, shredding metal.

In one of the galleries of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia are two bales of scrap metal. They come from Revolution Recovery, a recycling plant in Tacony that pulls metal out of the waste stream and compresses it into blocks measuring roughly 3 feet by 3 feet by 4 feet, about twice the size of a bale of hay.

On Wednesday evening, two guys will be standing on these bales of shredded metal, shredding metal.

“We’re jamming on a riff that I wrote,” said Jackson Durham, 15. “We’ve been mixing stuff we’ve written or somebody else has, mixing it all together. This is scrap metal — these metal blocks. We’re kind of taking bits and pieces of stuff and putting it together to make something awesome.”

Durham and Van Tingley, also 15, are the duo Metal Eyes, which will perform at the ICA on Wednesday evening as part of the University of Pennsylvania museum’s 50th anniversary series. Artist Mary Ellen Carroll invited the freshmen at Shipley School in Bryn Mawr to be part of her conceptual installation about waste and “waste music.”

In February, Carroll was invited by local artist Billy Dufala (through his project RAIR, Recycled Artist in Residency) to be the artist-in-residence at Revolution Recovery, scanning the waste stream for objects that could be repurposed as art materials. She became interested in how the plant operates. Recovering about 85 percent of material, Revolution gathers huge amounts of debris, sorts it into categories, and compresses the fragments into blocks ready for the scrap market. It is how it makes money.

“It’s very fast,” said Carroll by telephone from her Manhattan studio. “If something is identified as valuable, it would be pulled; otherwise it goes into the waste stream. To see the point of complete chaos — it can be overwhelming.

“You start to see the things in your life and reconsider having anything,” she said. “Then it goes through the sort line, and it becomes organized again.”

Carroll wanted to mimic that process of scrap-metal recovery by using the bales of shredded metal as building blocks. A few dozen were assembled into a stage, on top of which instrumentalists of all stripes were invited to shred. This happened for 12 hours on April 6.

“Informally, we were called it Shredfest,” said Dufala. “It quickly became the Waste Music Festival of Metal.”

Waste music — a genre largely coined by Carroll — comprises phrases, riffs, and gestures of previously existing music, recontextualized into something new. Carroll points to the work of Laurie Schwartz in Berlin, John Zorn in New York, and the drone-metal music of Matthew Bower as examples of waste music.

Conceptually, Carroll relates the music to the materials flowing through the waste-recovery process.

“Eighty-five percent, 90 percent of that is reusable in some way,” said Carroll. “But 15 percent to 20 percent goes into a landfill, and that’s where it’s not recognizable.”

“Waste music is what Mary Ellen and Billy call what we call jamming,” said Durham, gingerly stepping off of his scrap-metal riser at ICA. “Taking pieces of stuff we learn and repurposing it and throwing our own spin on it so it becomes this new thing.”

After the performance by Metal Eyes, the bales of shredded metal will remain in the galleries of the Institute of Contemporary Art for about a month. Then will go back to Revolution Recovery to be sold as scrap. Depending on market fluctuations, they are worth something shy of $1,000.

Check out a video of the performance here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.