SAT to the rescue? Why Delaware and other states are embracing a new role for an old test

Listen

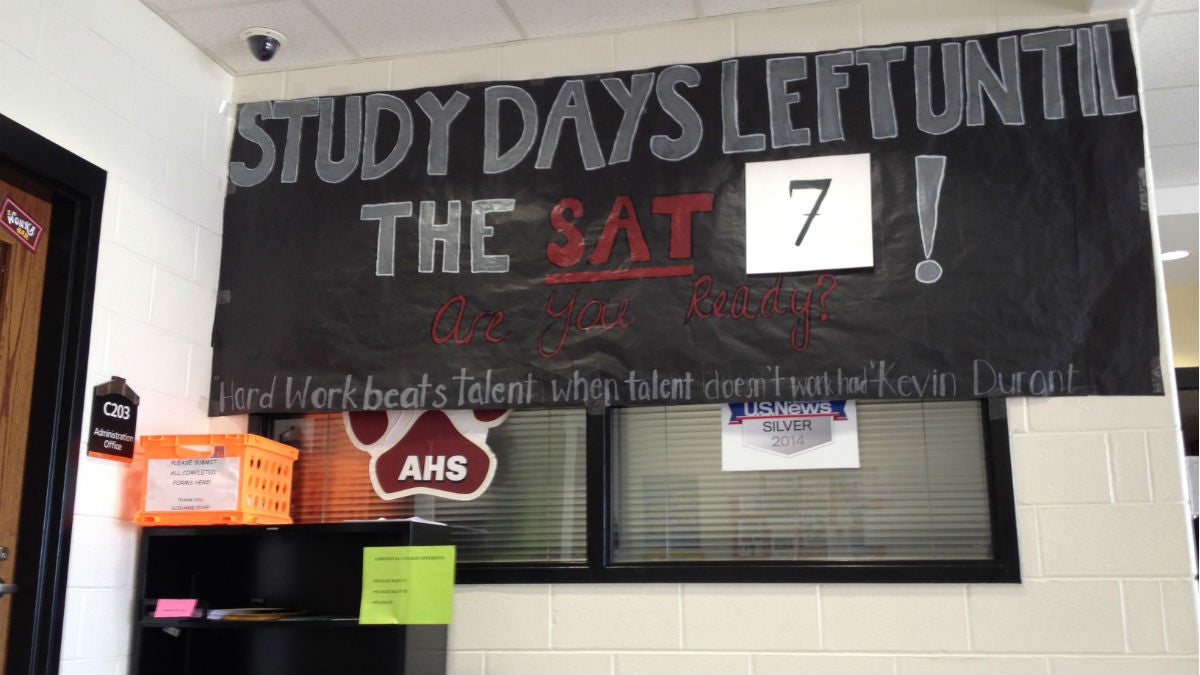

A sign at Appoquinimink High School in counts down the days until the in-school SAT. Delaware administers the SAT in every school. (Avi Wolfman-Arent

Can a new version of the SAT help states curb the anti-testing backlash? Delaware is one of five about to find out.

On April 12, Delaware’s high school juniors will take a standardized test. That in itself isn’t remarkable. Every year millions of kids across the country take statewide standardized tests. It’s a fact few students enjoy, and some adults decry.

Delaware, however, is one of five states trying a new exam that many hope will combat the anti-testing malaise. And in this case, that new exam is actually an old one: the venerable SAT.

Delaware, Maine, Connecticut, Michigan and New Hampshire will all require schools to administer the SAT this spring–and will then judge those schools based on how their students perform. Three states will do the same with ACT. Three others will use either the PSAT or its ACT equivalent, a test called ACT Aspire 10.

The moves mark a new era in high school assessment and establish a new front in the decades-old battle between SAT and ACT for testing supremacy. They also figure to appease students, parents, and staff frustrated with the purpose and volume of federally-mandated standardized tests.

But a larger question lingers: Will any of this help states better gauge how much their kids know?

The back story

First, a bit of background.

Over the last decade, states have developed a slew of new standardized tests. You probably know them by their acronyms. The PSSA in Pennsylvania. DCAS in Delaware. PARCC in New Jersey. These are all examples of accountability exams–tests used to determine how districts and schools are doing academically. The federal government requires states give an accountability test in grades three through eight and again in high school.

Last year, Delaware gave students a test called Smarter Balanced, which was designed to measure the extent to which students have mastered the Common Core State Standards. Third through eighth graders will continue to take Smarter Balanced.

The change comes in eleventh grade.

High school students in Delaware already took the SAT for free during the school day as part of a statewide program to encourage college enrollment. The difference is that those scores will now be used to evaluate schools, districts, and, eventually, teachers.

Meanwhile, juniors will no longer have to take Smarter Balanced.

Why now?

Two recent changes have encouraged states to use college-entrance exams as accountability assessments.

Late last year, Congress passed a new comprehensive education law to replace the No Child Left Behind Act. That new law, dubbed the Every Student Succeeds Act, permits states to use “nationally recognized high school assessments” for accountability purposes so long as they’re approved by the federal government.

Months later, the College Board introduced a new version of the SAT that is supposed to better reflect the skills students learn in school. The revised SAT eschews obscure vocabulary words and focuses instead on using words in context, analyzing passages, and other standards found in state curricula.

“The bottom line is this: Studying for the SAT should be no different than what students are doing in school,” said Cyndie Schmeiser, Chief of Assessment for the College Board.

Prior versions of the SAT were supposed to measure aptitude or intelligence. The new version measures whether students have mastered the skills they’re supposed to have mastered in school.

That’s precisely what accountability tests are designed to do. The College Board’s pivot allows it to market SAT as a viable accountability exam, whereas past versions would have been incompatible.

What’s in it for states?

Many states–Delaware among them–face growing pressure to reduce the number of standardized tests students take. Some of that pressure comes from advocates who decry the way states use testing results to sort schools and, on occasion, punish them for bad scores.

But just as much, if not more, of the pressure comes from parents, teachers, and principals frustrated with the amount of time students spend preparing for and taking tests. Using the SAT as an accountability exam could ease many of those concerns.

Smarter Balanced took as long as nine hours to complete and had to be taken on a school computer. Some high schools needed nearly a month to give the test and track down students who’d skipped it.

Schools also had to convince high school juniors–many of whom also take AP exams and college-entrance tests–to take the test seriously even though they had no personal incentive to do well.

“We really had to try to sell the previous assessment–sell the purpose behind it, the meaning behind it and the relevance, the importance of that assessment,” said Dean Ivory, principal at Glasgow High School in Newark, Delaware.

Students, meanwhile, are already motivated to do well on the SAT.

“Ever since I got into high school really–like freshmen year, out the gate–we’ve been hearing about the SAT and how everything leads up to this point,” said Aaron Hiliard, a junior at Middletown High School in Middletown, Delaware.

Last year, Delaware was one of 13 states to receive a warning from the federal government due to poor test participation rates. The problem was particularly acute among eleventh graders. About one in ten high school juniors never took Smarter Balanced. Swapping in SAT for Smarter Balanced will likely boost Delaware’s participation rates.

The move also figures to appease those concerned about over-testing. By using SAT for college entrance and accountability purposes, Delaware is taking one more test off the collective plate of its high-school juniors.

For building principals, SAT frees them from having to sell Smarter Balanced to their reluctant students. SAT is also a “dream come true when it comes to administration,” said Keisha Brinkley, principal at Appoquinimink High School in Middletown, Delaware. The SAT doesn’t require a computer and can be administered in a single day.

Delaware will also save about $100,000 by eliminating Smarter Balanced for 11th graders, according to Michael Watson, the state’s Chief Academic Officer.

There’s also a more charitable explanation for why states might prefer the SAT to other accountability exams. By giving the SAT in school, states might open doors for students who would not have taken the test on their own time.

Prior to this year, Delaware was among a small handful of states already administering SAT to students in school, free of charge. The purpose wasn’t accountability, but rather to improve college access. The in-school SAT was part of Delaware’s lauded “Getting to Zero” initiative, an effort to make sure every college-eligible student in the state applied to some form of higher-ed.

As a result, every Delaware public school student in the class of 2015 took the SAT, according to the College Board.

What’s in it for the testing companies?

The College Board is a non-profit organization committed to improving college access. Simply put, giving SAT in-school fits their mission.

“Maybe we have the best shot we’ve ever had to increase the number of kids who are college and career ready, increase access, and ultimately increase college completion rates,” the College Board’s Schmeiser said.

In 2015-16, more than 650,000 students will take the SAT in-school with either their state or district picking up the tab, according to College Board.

Not everyone, though, thinks the College Board’s motives are purely altruistic.

“It’s a big growth opportunity,” said Adam Ingersoll a California-based test-prep expert who blogs about the testing industry

Administering the SAT in school ensures that every student takes the test, not just those who are college-bound. Plus, it’s more efficient for the College Board to sell its test to states. Delaware, for example, will pay $370,600 to dole out 8,500 SATs this year.

“That market is easier to sell into because you’re selling at the state level or at the large school district level,” Ingersoll said. “So rather than grinding it out with the ACT and one student at a time to choose your test over the ACT, instead you sell it to the entire state.”

In many ways, Ingersoll said, the SAT is adopting strategies the ACT pioneered. This year, 16 states will administer the ACT in school, according to an ACT spokesperson. The ACT has used its partnerships with states, Ingersoll said, to surpass SAT as the country’s most popular college entrance exam.

But the College Board is starting to punch back. It recently convinced Michigan to switch from ACT to SAT. Illinois and Colorado are slated to follow suit next year.

“I do not believe that the College Board would have gone through the transformation it has gone through were it not for the fact that a) they had lost so much ground to the ACT and b) there was this really large marketplace opportunity to be the common assessment test,” Ingersoll said.

The College Board and ACT aren’t just fighting each other, though. They’re also fighting a revolt from higher-ed.

Earlier this year, the University of Delaware became the latest school to go test-optional. There are now more than 850 schools who no longer require students submit SAT or ACT scores when applying, according to the advocacy group Fair Test. (The College Board notes that many of these schools are speciality schools such as art schools, for-profit schools, or open-admissions schools. Still, the number of comprehensive, four-year schools is growing.)

Some believe the College Board and ACT are recasting their signature tests as accountability exams to hedge against the threat posed by this test-optional movement.

What are the potential hang-ups?

States like Delaware are happy to embrace the SAT as an accountability exam. The College Board is happy to serve as an accountability exam.

None of this, however, speaks to whether the SAT is actually a good accountability exam. Does it test the right things? Does it paint an accurate picture of what students know and how well schools are performing?

It’s hard to answer that question right now since the College Board just introduced a new version of the SAT. But plenty of folks are skeptical.

Old tests such as Smarter Balanced may have been lengthy and complicated, says Derek Briggs, director of the Center for Assessment, Design, Research and Evaluation at the University of Colorado, but they were lengthy and complicated for a reason.

“That reason was that the Common Core promised to get at depth of student knowledge in a way that hadn’t been measured before,” Briggs said. “The drawback to tests the SAT and ACT is they take less time, but they don’t attempt to get at these higher-order thinking skills.”

By cramming accountability and college-entrance into one assessment, states are asking the SAT and ACT to do some serious heavy lifting.

Traditionally, college-entrance exams are designed to “rank individuals along some well-defined continuum,” said Li Cai, co-director of UCLA’s National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing. Accountability exams are built to measure all students against some predetermined benchmark of what they’re supposed to know and then point to possible interventions when students fall short.

Those may sound like abstract distinctions, but the point is this: Any test is created with a distinct purpose in mind. Everything about its structure points back to that core purpose. It’s not easy to create a test with two core purposes.

“I would say it is going to be fairly difficult to do both efficiently with reasonable cost within the same testing program,” Cai said.

States are now trusting that College Board and the ACT have managed this feat. And that takes a lot of trust.

A final question

All of this leaves us with a question. And it’s one perhaps best answered by you.

Is this new alliance between states and the SAT:

a) A marriage of convenience?

b) A cash grab by College Board?

c) A win-win that reduces the burden on over-tested juniors?

d) All of the above.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.