Philly-area parents search for RSV antibody shots as winter approaches

The newborn RSV antibody shots offer protection against severe illness for at least five months, but they may not be widely available until next year.

Listen 4:22

Heather and Amber Mackson’s daughter, Bradley, was hospitalized with RSV-induced pneumonia in June 2022. Bradley was about 6 months old and spent over a week in the hospital on oxygen and medication. (Courtesy of Heather Mackson)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Anna Christensen gave birth to her daughter in Philadelphia in January of 2023, one month prematurely.

The baby had lung issues and spent nearly four weeks in the neonatal intensive care unit on oxygen. Hospital staff told Christensen that her daughter’s early health challenges would make her vulnerable for future ones.

“When she left the NICU, we were basically told that when she gets RSV or COVID or the flu, you can plan to be back in the hospital just because of the way that her lungs started out,” Christensen said.

So, Christensen felt relieved when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a single-shot monoclonal antibody treatment in July that could protect babies from RSV, or respiratory syncytial virus.

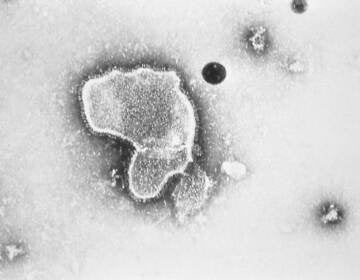

It’s a preventative drug for RSV, which is the leading cause of hospitalizations for thousands of infants and newborns every year. It typically causes no more than a mild cold in healthy older kids and adults.

Christensen said it was a no-brainer that her daughter would get the shot. The family didn’t want to chance that their youngest could end up back in the hospital, hooked to oxygen and medications.

But now that fall is here, Christensen and other families are still searching for answers to basic questions, like when and where can they get the shots, what will insurance cover, and will their children be eligible?

Doctors and health care providers say they don’t have some of those answers yet, and predict that it’ll be another year before the new antibody treatment is widely available to most families.

“I think we’re all aware that this will be a bit of a transition year,” said Dr. Lori Handy, a pediatric infectious disease expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “We won’t get full uptake. We won’t be able to get to every single person that we want to, just because implementing in a short time period is challenging.”

Excitement, and then a frustrating wait

Nearly everyone becomes infected with RSV, often multiple times, in their lifetime. Most people easily manage and recover.

But when an RSV infection spreads to the lower respiratory tract, it can cause pneumonia or bronchiolitis. Older people, those with immunocompromised or chronic conditions, and babies are at the highest risk of complications.

Between 58,000 and 80,000 children younger than 5 years old are hospitalized with RSV every year in the U.S., and about 300 die, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new monoclonal antibody medication for newborns is nirsevimab and sold under the brand name Beyfortus. It is not a vaccine, but is administered as an injection into the arm or leg. It mimics the immune system’s ability to fight infection and provides short-term protection against the virus for at least five months.

The CDC recommends one dose for infants younger than 8 months who are born during or entering their first RSV season, which runs from about October to May.

Another dose is also recommended for children 8 through 19 months who are at high risk of respiratory complications.

Clinical trial data showed that the antibody treatment reduced severe RSV illness by 70% to 75% in infants born prematurely or at term, respectively.

Christensen said she remembers feeling excited about the shot’s efficacy. But that excitement eventually gave way to frustration as the seasons changed and she started looking for this shot for her now 8-month-old daughter.

“People are really pushing it, and then you go to ask your pediatrician for it and they don’t have it. They don’t know when they’re going to get it,” she said. “They’re giving you all the information they have and that information is very limited. And then your baby ages out of it. It’s frustrating to have that sort of delay cause barriers to access.”

A difficult implementation

Health care providers are working to troubleshoot some of these barriers, and manage expectations.

Handy said CHOP’s primary care offices should have a supply of the new antibody shots sometime this month. She expects other pediatricians will, too, but there’s no exact timeline.

Health experts say the prime window for giving an antibody shot to a newborn is immediately after birth, before they even leave the hospital.

But that presents another logistical challenge, since labor and delivery units historically don’t administer many childhood immunizations. They may not already be enrolled in Vaccines for Children, a federal program that provides vaccines at no cost, or childhood immunization reporting databases.

Providers are also still waiting to see if insurance companies will fully cover the new treatment. Insurers have up to one plan year to make decisions.

“We have something that’s new, important, able to really impact every single child,” Handy said. “We are eager to have them do that sooner rather than waiting a full plan year just because of the time sensitivity and the potential impact for kids.”

Dr. Sarah Long, professor of pediatrics at Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, said the antibody treatment’s high price tag could be a factor in insurance and provider reimbursement decisions.

One dose of nirsevimab can cost about $500, according to ordering information from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“It is costly for health care systems, for states, for the federal government, for individuals, potentially,” Long said.

Labor and delivery units will need to figure out how to incorporate the shot into their birthing services, which are usually billed to patients at pre-negotiated bundles of charges.

Primary care offices may have to put out some money upfront just to be able to get an initial supply, which Long said could put a heavy burden on health care providers who are already on the lower end of insurance reimbursement amounts.

All of that, Long said, could lead to equity issues concerning who can offer, access, and pay for these shots in the early rollout.

“It is an extremely expensive intervention when you think about the population of children who are going to get it. Where’s all that money going to come from?” she said. “It will require people being their best selves in the insurance industry, in hospital administration, in state administration, in public health departments, to be able to do the right thing.”

Will my child qualify?

The antibody treatment comes with recommended age limits and expanded use for high-risk children, which the American Academy of Pediatrics defines as those with chronic lung diseases, children who are severely immunocompromised, and children with cystic fibrosis.

But families like the Macksons hope health care providers will have flexibility and discretion when administering doses.

Heather and Amber Mackson live in Middletown, Delaware, with their two daughters. Their youngest, Bradley, was born with three congenital heart defects and Down Syndrome, which puts her at an increased risk for autoimmune disorders and infectious diseases.

But that still might not be enough for 21-month-old Bradley to qualify. Amber Mackson said they’ve appealed to her daughter’s pediatricians, cardiologists, and specialists, but nobody can tell them for certain if they’ll be able to get a shot.

“What is it going to take?” she said. “Children with heart defects, they’re fighting a little bit harder and you want to throw RSV at them and make them fight for their lives? I don’t understand.”

The Macksons have another reason to fear RSV. Bradley suffered a severe case of the virus at just 6 months old. She was hospitalized for longer than a week in June 2022 as she recovered from RSV-induced pneumonia.

Amber Mackson said the experience was traumatic and scary — and something they never want to repeat.

“We are terrified of her getting sick again with it,” she said. “But what can we do?”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.