Rodin’s radical public monuments on display in Philadelphia

The Rodin Museum in Philadelphia keeps alive a discussion about public monuments started in 2017 by the Monument Lab.

Curator Alexander Kauffman describes the role of Picasso's "Man with a Lamb" in the Rodin Museum exhibit, "Rethinking the Modern Monument." (Emma Lee/WHYY)

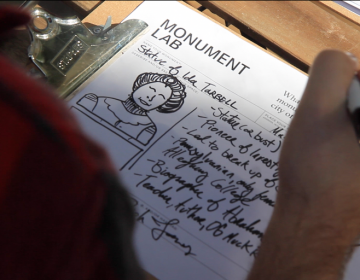

In late 2017, the city of Philadelphia had a long conversation about public sculptures as the Monument Lab asked residents what would be appropriate for the city.

That conversation is extending into a new exhibition at the Rodin Museum on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For the next two years, “Rethinking the Modern Monument” will demonstrate that the same questions posed about public monuments have been asked, and fought over, for at least 100 years.

Auguste Rodin’s famous statue “The Thinker” and his big, meaty figures rising from rough stone are classics now; he is considered the father of modern sculpture. There was a time when Rodin’s work was the very vanguard of controversial art and, as such, the objects of vitriol.

His “Monument to Balzac” (1897) was said to be a monument “to what perilous degree of mental aberration we sank at the end of our century” (James Rameau, Le Gaulois, 1898).

Regarding the “Burghers of Calais,” Alphonse de Calonne wrote in Le Soleil in 1889, “Here it is a convolution of limbs and contortion of muscles that could only be envied by the clowns in our lowest spectacles.”

To which Rodin replied, “I am a sculptor who, like you, asks only to make a masterpiece.”

“We have lots of letters from the commissioning body saying, ‘This is not what we wanted. You have to change your design,’” said exhibition curator Alexander Kauffman. “Rodin puts his foot down and says, ‘It’s either this, or I’m leaving.’”

Kauffman put together this exhibit of 80 sculptures by Rodin and others showing the tension between traditional, heroic monuments and more complex public sculptures. The bi-annual exhibition overhaul of the Rodin Museum includes 24 sculptures newly installed into the small building on the Parkway.

Consider the two Joans of Arc.

On the left side of the gallery is a golden maquette of Emmanuel Frémiet’s “Joan of Arc,” a miniature version of the larger-than-life statue erected on the Parkway. The teenage commander leading the French army against the English during the 100 Years War is sculpted like an empress of war, hoisting the French flag in her right hand, completely gilded in gold.

On the right is Rodin’s “Head of Sorrow (Joan of Arc),” a public commission that was ultimately rejected. The visage of the French heroine is shown in the moments of her death, burning at the stake. Her expression can be read as either the mortal pain of flames or a spiritual ecstasy ﹘ or some combination of the two.

Both commissions were made in the aftermath of the crushing French defeat by the Germans in the Franco-Prussian war ﹘ and the subsequent rise and suppression of socialism in Paris. In the national tumult, France yearned to remember the pride of its past glories, all the way back to the 14th and 15th centuries in the case of the burghers of Calais and Joan of Arc.

Rodin was not interested in staging Joan alone on a horse, as Frémiet did; it didn’t seem like the best way to represent a modern republic.

“Even in the U.S., monuments to George Washington and the founding fathers are still using the language of European emperors and kings, presenting heroic individuals on a horse as military leaders,” Kauffman. “People have a lot invested in these old styles. They want to feel connections to the kings of the past. But those values are not our values anymore.”

Kauffman said he was directly inspired by the events of the summer of 2017 when statues of Confederate soldiers were removed and by the Monument Lab experiment in Philadelphia that fall, which asked the same questions: Who decides what a public monument is?

One of the pieces in the exhibition is Pablo Picasso’s “Man with a Lamb,” borrowed from the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection. (While the Rodin Museum is operated by the art museum, the two have separate collections; this is the first exhibition that combines objects from both). Picasso made it in 1943, in the midst of the Nazi occupation of Paris.

Picasso was not commissioned to make the figure of a nude man holding a squirming, bleating lamb, nor did he have any idea where it would be located if it ever found a home. Supposedly, he didn’t even have a strong idea of what it is supposed to represent. It’s a work of imagination, with no determined purpose.

“It was really a work of optimism,” Kauffman said. “He was creating it under dire circumstances when there were shortages of materials. He was under threat daily. The choice to create, that is something I’m still grappling with. Why was this the most pressing thing to do in that moment?”

Later, after the war, a version of the sculpture was erected in Vallauris, France, where Picasso was living in 1950 and had been a headquarters for the French Resistance fighters he admired.

What exactly it means is up to interpretation. Some see a shepherd with religious connotations. Others see a memorial to the French Resistance. Still, others may see an existential struggle of civilization attempting to control a wilder nature.

It’s a statue with an ambiguous message.

“That is the modern monument in a nutshell,” Kauffman said. “To break away from the authoritarianism of a single message, to allow for a more democratic monument that can be seen in many different ways.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.