Rethinking high-poverty schools: An interview with Dr. Robert Balfanz

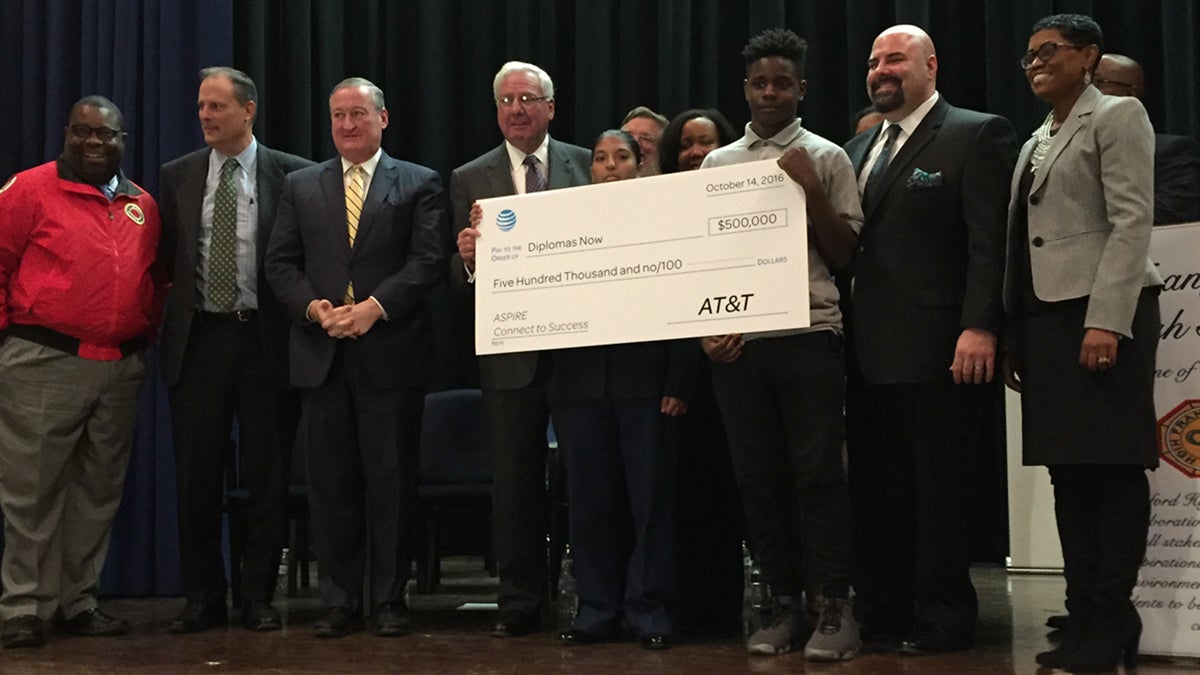

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney (third from left) and others accept a $500

The freshman class at Frankford High School in Northeast Philadelphia faces long odds. But on Friday they might have gotten at least a little better.

The neighborhood high school— where 85 percent of students are economically disadvantaged and just 59 percent graduate on time, according to state numbers — received a $500,000 check from AT&T. The money will support a new initiative designed to identify students at risk of eventually dropping out and bombard those students with extra support.

The program is called Diplomas Now and actually emerged out of research conducted right here in Philadelphia (more on that later). Today Diplomas Now operates in 29 schools across 13 cities. Philadelphia now has two of those schools: Frankford and Grover Washington Middle School.

The program targets sixth and ninth graders. Using attendance, discipline, and academic data, teachers identify students whose record suggests they may soon leave school. These so-called “early warning systems” have been in vogue for a handful of years, but some evidence suggests simply giving teachers a heads up on troubled students isn’t enough. Too often no one knows how to act on the information.

Diplomas Now tries to ameliorate that by providing extra “people power,” says co-founder and Johns Hopkins researcher Robert Balfanz. Recent college graduates working with City Year adopt small groups of students and basically bug the heck out of them, making sure they show up to school on time, stay out of trouble, and complete their assignments. Another non-profit, Communities in Schools, helps students facing extraordinary obstacles outside the school walls.

The first school to receive the Diplomas Now treatment was Feltonville School of Arts and Sciences, a middle school in North Philadelphia. That was back in 2008-09. Feltonville has since phased out of Diplomas Now, says Balfanz. (For what it’s worth, Feltonville does not score well on the district’s school progress report, although those reports do not track the corresponding high school graduation rate of students in a given middle school.)

Newsworks/WHYY interview Balfanz to hear more about Diplomas Now, how it can be sustained on a larger scale, and what the future should look like for high-needs schools.

Q: The Class of 2020 here at Frankford, what are they getting that their predecessors didn’t have?

RB: One of the things we’ve learned is that for kids to succeed, especially when they live in higher poverty neighborhoods, is they actually need help getting to school everyday, staying focused in class, and getting their work done. It may seem simple, but that’s where kids fall behind. In many of our large cities, half of our high school kids miss a month or more of school. Many of them when they get to class are distracted by life outside of school and the struggles of living. And many struggle just to get their assignments in. Many times when kids fail it’s not because they’re failing a test, it’s because they didn’t get five assignments in. So we’ve found if you organize a team of folks to help them–including City Year corps members–each of them can shepherd maybe 15 kids through the day. Make sure they get their. Make sure they’re focused in class. Make sure they get their work done. And then we learned you need someone like Communities in Schools for the kids that have serious out of school problems. If you don’t fix those it doesn’t matter how great school is.

And finally what we know is that teachers have to be at the core of this, because kids come to school for their teachers. And that’s where we work with an early warning system where we have teams of teachers that share the same kids, get together once a week and actually talk about their kids. And see are they coming to school? Are they staying out of trouble? Are they getting their work done? And if not they can pool their insights. Each teacher has a different part of the puzzle. And unless you create a space where they can put that puzzle together the kids don’t get the help they need.

Q: When you say early warning system or indicator, what’s an example? Is it a number? Is it a metric?

RB: What we’ve found, ironically, is it’s the ABCs. You make sure kids are attending and not missing more than 10 percent of school. You make sure they’re both not getting in trouble, but this idea that they’ll actually be able to pay attention in class. And finally you’re making sure the get their work done and pass their classes. If you make sure they come, get their work done, and pass classes they will graduate.

Q: What distinguishes this from other early warning systems? Because this isn’t a new idea, right?

RB: It’s big data meets the human touch. You need the data to analyze who really to help. Sometimes you get wrong in your guesses. We had a really recent finding that found one third of the kids that enter ninth grade or sixth grade proficient academically — you think they’re good, they’re set — still end up chronically absent or get in trouble. So you have to monitor everybody. And to do that you need the person power to do it. Because if you just tell teachers, monitor your kids they go oh my God there’s a hundred kids chronically absent I’m overwhelmed. What do I do?

What Diplomas Now does is it provides the person power. What it really does it bring people power into the school to enable us to get the right intervention to the right kid at the right time.

Q: You said communities in schools is responsible for helping “fix” what’s wrong outside the school. But that sounds difficult. What does that really mean?

RB: I guess fix is too strong, but to help ameliorate the impacts. They’re the ones [that can] connect families or kids to existing social services or youth services. If the family’s been evicted how do we help them get their kid to stay in school and not lose a lot of time? If they need referrals to mental health supports, know who the people are who can actually help them and make good referrals. It’s things like that

Q: It sounds like a lot is required. And so what’s the promise for trying to scale something like this up?

RB: What we’re trying to do, and we actually just did a large, national randomized trial, is really just to build the evidence base to make people [think] this is just how school should be organized. Especially high-needs schools.

That’s the challenge our nation faces. We put our highest-needs kids in a subset of schools that weren’t designed for it. The building we’re in was built in 1910 for a whole different idea. And now it only largely educates kids that live in poverty or near poverty. And schools aren’t designed for that. So we have to help them redesign it by bringing in additional person power, but in a way so folks eventually see that’s just what we have to do in these schools. If we have high needs we need additional supports. And our goal is to try to show that should be normal, not sort of exceptional.

Q: Realistically what does success look like for the class of 2020? How would we know if this worked?

RB: If there’s a markedly higher graduation rate. It’s pretty simple — more diplomas earned on time.

Q: What’s markedly higher?

RB: Our goal is 15 to 20 percentage points higher.

Q: I recall reading about this at Feltonville Arts and Sciences in Philadelphia. But they aren’t listed on the website as still participating. Are they still participating?

RB: After we’ve supported a school, we supported them for almost eight years, then we try to build the capacity so they can continue. So that’s sort of where they are. They’re in a self-sustaining mode.

Q: Do you have any sense of whether the work has carried on there? Has it really sustained?

RB: I’ve not been back in the past year. As of a year ago I’d say yes. But since then I don’t know.

Q: Sixth and ninth grade — they are entry-point grades. Is there anything more to it than that? Why do you pick those grades?

RB: How we got to these early warning indicators is we actually started in Philadelphia and we tracked in the middle 00’s all of the sixth graders in Philadelphia through to a couple years post graduation to try and understand what the key indicators were. What was the smallest number of indicators you could have that would give you the largest number of kids? That’s where we came up with chronic absenteeism, misbehavior, and course passing

Q: So these students are getting help in ninth grade. How does the help follow them through?

RB: What we found is sixth and ninth grade are the key transition years. Because in sixth grade you’re usually going to a new school. And it’s also in early adolescence you make decision: Is schooling for me? Is this something I’m going to invest in even if it’s boring, even if it’s like I’m not learning? Or is it just something I try to endure as long as I can? And if you do that, it’s hard to succeed.

Ninth grade is critical because the rules of the game change. In ninth grade you now have to pass classes to earn credits. Kids that repeat ninth grade almost never make it.

Diplomas Now is actually designed to support kids all the way through. It’s most intensive in ninth grade. But we continue to try to build those supports and actually have the teachers continue the early warning meetings in the upper grades. We know we have to give the kids support all the way through after turbo-charging the transition years.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.