Requiem for a new urbanist dream

When PennDOT announced that it was replacing seven bridges over the Vine Street Expressway without taking the opportunity to also cap all four of the ventilation openings amongst them, a Greek chorus of new urbanists bemoaned this as yet another example of Philadelphia’s shortsightedness. But like a Greek tragedy, Philadelphia’s apparent failure to seize this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity comes to us as a complicated history of characters moving unaware of others actions and their own flaws, rather than a simplistic morality play lamenting the sins of myopic planning.

Before this tale can be told in earnest, prologue is in order: back in 1957, our forefathers built an expressway along Vine Street to connect the Schuylkill Expressway to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, sinking it below grade to allow the expected 25,000 daily cars to zip along at 50 MPH. According to a 1950 Planning Commission proposal “[t]he possibility of an open cut through Logan Circle was considered, but [the Commission] recommend that the roadways be covered by subway grating,” because they felt it was “wise to retain as much as possible of the established distinction and future prospects in this area of impressive public, quasi-public and private institutions.” The result was what we have today: a two mile long river of 106,000 vehicles per day travelling I-676 at either 75 or 7.5 MPH (but rarely something in between), cutting Logan Square and the rest of Center City off from the Free Library, the Family Court Building and other “impressive public, quasi-public and private institutions.”

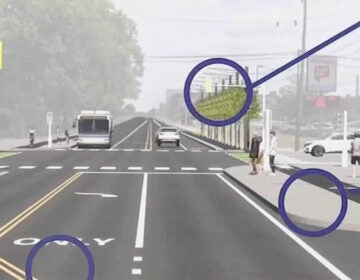

From 18th Street to 22nd, there are seven structurally deficient overpasses in serious need of replacement and four ventilation openings amongst them, creating impassible chasms in the streetscape above the highway. As part of a five-year, $82 million replacement project for those seven bridges, PennDOT plans on capping the smallest gap – a 5,625 square foot trapezoid-shaped bit between the oft-overlooked Shakespeare Park and 20th Street – and making considerable improvements to the streetscape along the expressway. Given that nothing legally compels PennDOT to spend its limited funds on planting shrubs, placing benches and installing new lights, this seems laudable.

But to a small – yet vocal – group of new urbanists, the failure to seize the chance to cap all the holes is just the latest example of Philadelphia’s most tragic flaw: accepting the incremental over the monumental, taking “better than it was” rather than demanding “the best it could be.”

The Critique

“It all should be covered,” David Searles, president of the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, told the Inquirer recently. “There’s no reason for it not to be, other than money.”

Searles’ statement summarizes the attitudes of other supporters of covering the Vine Street Expressway. More importantly, his statement succinctly illustrates why the cap dream remains an eminent reverie instead of imminent reality: it suggests that funding alone is the culprit here, as though money were a force of nature, uncontrolled by men. Money is the scapegoat for troublemakers like political inertia, institutional indifference and ineptitude.

The Logan Square Neighborhood Associated declined to speak with PlanPhilly for this article.

Kyle McShane, who launched a website and Facebook group a few months ago called Cap 676, doesn’t blame a lack of money, but he is frustrated by the lack of information. “[PennDOT] said they looked at capping, but it was too expensive – that’s it. It didn’t say how much,” McShane said. “It would have been great if they could have put out more info about that study about capping it.”

PennDOT’s Stance

“The I-676 project was driven by the critical need to maintain a safe transportation system in Philadelphia by taking down seven bridges in poor condition,” wrote PennDOT spokesman Eugene Blaum in an email.

PennDOT’s been worried about the condition of I-676’s overpasses since at least 2007, when preliminary engineering on replacing them began. While the small gap’s walls can handle the additional weight from capping it, “[t]he remaining walls between other bridges over I-676 would need to be completely rebuilt or have major modifications to be able to support the additional weight of widened bridges,” said Blaum. Add in ventilation systems and emergency egress tunnels, and the costs – and construction time – became more than PennDOT was willing to even consider, let alone bear.

When PlanPhilly asked for precise figures, Blaum replied that the “order of magnitude estimates indicated anywhere from tens of millions to as much as doubling the entire cost of the project for a full covering from 18th Street.” The implication is that PennDOT saw enough to decide that capping the remainder would be cost prohibitive for them, and moved on without bothering to calculate a more precise estimate.

A missed opportunity…

“This is a huge opportunity,” Kiki Bolender, an architect and Design Advocacy Group board member, told City Paper last year. “It’s worth asking if they’re using our money in the best way.”

On the Cap 676 website, McShane wrote “Although we will try to focus on the fact that the capping of 676 is set to begin, it is hard to not think of this as a missed opportunity. This seems like the perfect time to cap all of Logan Square while traffic is already being interrupted to repair the bridges.”

Writing for PlanPhilly in September, David Curtis admitted “[i]t’s too late to modify the project outline“ while still hoping “local leaders [would] waste no time in asking PennDOT to assess the cost of capping the three gaps as a separate project.”

But even with the necessary plans in place, it seems unlikely that PennDOT – or the commuters who rely on I-676 every day – would be willing to close lanes any time soon after the five-year construction on the region’s already most congested road ends. It’s now, as part of this five year construction project, or never.

Curtis, and many other advocates, point to Dallas’s Klyde Warren Park as an illustration of what Philadelphia is passing up: a 5.2 acre, award winning park that’s sparked a real estate boom and garnered national praise. Using Klyde Warrens’ $110 million price tag as a baseline, Curtis estimated that “it would run roughly $14 million to cap the three gaps in Logan Square, [which] total two-thirds of an acre in size.” While large fixed costs, like a ventilation system, would mean a lid on 676 would probably cost more than $14 million, the point remains: this project might be tantalizingly affordable. But, without a study crunching the hard numbers, we’re left speculating.

But this line of reasoning begs the question: why is any of this PennDOT’s responsibility?

…But is that PennDOT’s fault?

Chuck Davies, the assistant executive for design in PennDOT’s Distict 6, gets that capping I-676 along Logan Square “was desirable and understandable.” But for Davies, there are simply more pressing needs for PennDOT’s limited budget, like trying to keep Pennsylvania’s 5,200 structurally deficient bridges from collapsing. All seven of the bridges being replaced are structurally deficient, meaning they exhibit high levels of deterioration and require immediate maintenance and rehabilitation.

Even after the passage of Act 89, which raised fuel taxes in order to fund much needed infrastructure projects across the state, the American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that “more than 50 percent of the needs for state bridges and more than 60 percent of the funding needs for local bridges will still not be met in 2019.”

By October 2009, Inga Saffron was reporting on PennDOT’s plans: “[The] state says that capping the other three openings would be too costly. Maybe so. But there will never be another chance like this to repair the damage done to the square by the expressway.”

According to Mark Focht, Philadelphia Parks & Recreation’s First Deputy Commissioner of Parks and Facilities, PennDOT held “several meetings” starting in 2007 “where people could have gotten engaged.”

To Focht, this wasn’t “a lost opportunity to talk or consider” capping I-676 – that happened. “It was a lost opportunity to do it.”

The leadership void

Throughout the multi-year process, PennDOT’s plans weren’t just the favorite choice. They were the only choice.

PennDOT’s recent crop of critics point to similar projects in other cities that hid unsightly transportation lines under transformative parks, like Millennium Park in Chicago and Klyde Warren Park in Dallas. The Woodall Rodgers Freeway over Klyde Warren Park seems perfectly analogous to the Vine Street Expressway – a point PennDOT disputes, noting that the Dallas freeway’s walls were designed to support extra weight, whereas 676 ventilation openings were not.

But debating structural differences only distracts from the dispositive distinction between these projects: leadership.

The idea for Klyde Warren Park emerged from Dallas’s real estate industry, which quickly convinced the Dallas Chamber of Commerce to take a leading role early on. That led to a “diversified who’s who of Dallas,” according to Jody Grant, former chairman of Texas Capital Bank and chairman of the Woodall Rodgers Park Foundation, a 501(c)(3) created specifically to support the creation of the park (“diversified” apparently means something different down in Big D – the closest thing to a minority on the Foundation’s board seems to be a redhead – but I digress). The well-connected, and well-heeled, Foundation gained support from the Texas Department of Transportation and the City of Dallas, but not before first commissioning a $3 million feasibility study. With that study in hand, the Foundation secured $20 million from the city, $20 million from the state, and $16.7 million from the federal government, leaving $55 million – half the construction cost – which they raised in private donations.

Similarly, Millennium Park was the brainchild of Chicago’s famously powerful “Mayor for Life”, Richard M. Daley. When Seattle placed lids on its highways, it was the citizen there who forced the state agencies to act. Milwaukee’s mayor led the push to demolish a section of the East Park Freeway.

We don’t need to look as far as Texas or Illinois to find examples of what went wrong, says Parks & Rec’s Focht. “I think a closer analogy is to look at Penn’s Landing, and what the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation is planning, in terms of a cap over I-95. You have PennDOT saying that’s a possibility… talking about combining federal and state dollars to do that.”

Even closer to Logan Square, the redevelopment of the Reading Viaduct and the City Branch of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad into a 3-mile linear park helps explain what went wrong. Incorporated in 2010 – a full year after Saffon’s Inquirer column warned the Expressway’s neighbors of the fleeting chance to cap it – the Friends of the Rail Park started with grassroots fundraising. That eventually sparked interest from the region’s foundations, which led to state grants and preliminary designs. Just a few days ago, the Friends of the Rail Park announced the finalization of the Park’s first phase, and that the Center City District has secured “nearly 50% of the expected $8.5 million in construction costs.”

From Seattle to Spruce Street, not one of these transformative proposals to remove, bury or otherwise hide a highway came from a state highway agency. But no one – other than a loose collection of journalists and late-to-the-party activists like Cap 676’s McShane – has shown a similar willingness to try scrounging up the money to look into alternatives to the relatively milquetoast PennDOT plan – let alone attempt to corral local, state and federal agencies and raise matching funds to cover the Vine Street Expressway

When asked for comment, Mayor Nutter’s office simply noted that PennDOT was funding and designing the project. Council President Darrell Clarke, who represents the entire area, was only willing to go on the record with platitudes about the sorry state of national infrastructure (to be fair, council usually defers to the mayor on major infrastructure projects like this.)

Even though, according to Focht, “Paul Levy was always a strong advocate” for capping the interstate, his Center City District gave up this fight long ago. Back in 1999, the CCD issued a 60-page proposal that would have, among other things, covered I-676. As you probably guessed, that vision was never realized, and Levy turned his focus towards more incremental changes, such as the celebrated redesign of Sister Cities Park and the long overdue replacement of Dilworth Plaza with Dilworth Park.

When asked to comment for this story, Levy decided to applaud the improvements rather than lament the wasted potential, writing in an email that the CCD “developed plans for the redesign of the intersection of 20th Street, the Parkway and Winter Street in order to shorten the crossing between the Franklin Institute and the Barnes. We are delighted to see this incorporated into the final plans.”

While the Logan Square Neighborhood Association would have been clear beneficiaries of a covered expressway, and could have turned to the developers behind the estimated $2 billion in real estate investments proposed for the area, they apparently never attempted to produce a real alternative to PennDOT’s plan.

Add the cultural institutions, state representatives, the ex-governor, regional planners and private foundations, and there are a dozen others to point the finger for this project’s failure.

In the absence of civic entrepreneurship presenting an alternative vision, PennDOT’s proposal was the default. Philadelphia’s lucky they worked with Parks & Recreation to incorporate the Ben Franklin Parkway’s design specifications, given the city’s historically awful relationship with the agency.

It’s only human to want to find someone or something to fault for a hopeless situation. The Greeks blamed the Gods when Fortune did not cast her favor, like Philadelphia blames money and Harrisburg. But it’s suffuse responsibility and the city’s fear of dreaming big, not Fate, keeping us from an epic Philadelphia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.