In remembering Vietnam War, more stories of Lao refugees deserve to be told

Ken Burns' "The Vietnam War" reminds me yet again why it is so vital for refugees to tell our stories in our own words and on our own terms.

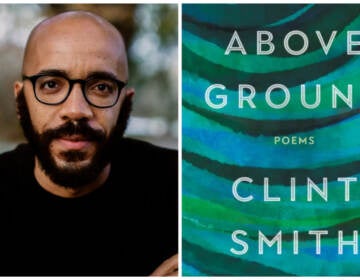

Author Bryan Thao Worra is a Lao-American writer whose work appears internationally. (Image used with permission)

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War.” WHYY members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

—

People around the country have been asking what I think of the new Ken Burns documentary “The Vietnam War.” As a Lao-American poet with roots in the Midwest, and part of the first generation to arrive as a direct consequence of the wars in Southeast Asia, my approach is a bit different from most people’s. Adopted by an American pilot who had been flying for Royal Air Lao during the final years of the war, I’ve spent most of my life trying to see as many sides of the issue as possible.

While I applaud Burns’ attempt to provide the U.S. with a way to feel closure, so many stories were left to the wayside. “The Vietnam War” reminds me yet again why it is so vital for refugees to tell our stories in our own words and on our own terms. I hope viewers won’t walk away thinking anything close to the final word has been written on the war, because it hasn’t.

I feel a deep empathy with the Vietnamese Americans who asked, if “The Vietnam War” was so committed to hearing all sides of the story, including the perspectives of the South Vietnamese who were among the most heavily and directly affected, why couldn’t the narrator and others be bothered to pronounce Vietnamese names, and so many Southeast Asian cities and landmarks, correctly. My ongoing concern is for those the U.S. has so often found it convenient to forget, such as the veterans and civilians caught in the wars for Laos and Cambodia.

It feels like every other day my community meets someone who is just now discovering Laos, after we have lived among you for four decades. Only now are they learning about the nearly half-million refugees from my homeland who are rebuilding their lives here because of the “Secret War” — an American-driven war that left over 30 percent of the countryside, to this day, contaminated with cluster bombs long after the bombing ended in 1973.

A generation later, almost no one knows who we are, and so often, outsiders try to reframe our narrative to their benefit and glorification. Often, our presence in the U.S. has been cited as a demonstration of American generosity, with refugees used as a wedge issue in debates on social justice. Growing up, I remember being reminded by neighbors and family to be grateful for what I had here, and not to question the wisdom of the U.S. violating the Geneva Accords in Laos.

The Secret War in Laos saw the U.S. use covert armies of regional minorities to advance its policy. This had devastating consequences for the local tribes involved in the fight, including the Hmong, Tai Dam, Iu Mien, Khmu, Nungs, Lue, and others armed by the CIA and encouraged to stop enemy armies using the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Spoiler alert: Many of the U.S. paramilitary advisors in the Secret War didn’t quietly retire after the war, sipping Mai Tais on the Riviera. Their approach to using proxy armies, in addition to the Phoenix Program’s approach to assassinations taught the U.S. government lessons that would be applied for decades in flashpoints around the globe, as we saw with efforts to arm the Kurds of Iraq and the Mujahideen of Afghanistan.

Today, there are fewer than 40 books by Lao refugees in our own words after 40 years here, and I believe more of our stories deserve to be told. Some ask why I try to address our journey through poetry. In today’s short-attention-span society, I rarely got more than five minutes at a time to talk about what it means to be a Lao refugee, even in events organized by Asian-Americans. Poetry proved to be among the most efficient art forms to get our experience across to others.

I remember being deeply moved by the poetry of the Vietnam veteran Yusef Komunyakaa when I first began writing. His poem “Facing It” and his book “Dien Cai Dau” still linger with me in the decades since I first read them. But I’m also saddened that there have been so few voices from the Lao and Cambodian communities that were nurtured to speak to their experiences. Around the early years of this century, I came across the book “Poems from Captured Documents,” a short collection of poetry written by mostly anonymous North Vietnamese soldiers killed during the war. These poems were among the only ones preserved from the American archive of North Vietnamese documents being destroyed by the U.S. government to save storage space. In the years since, I’ve often wondered what it means that their families will likely never read the final poems of their sons and daughters. Southeast Asian Buddhism teaches us we can’t be attached to such thinking, of course, but nevertheless …

These days, I look at the poetry of writers like Kevin Minh Allen, a Vietnamese-American who’d been adopted outside of the Operation Babylift program, and that of Brandy Lien-Worrall, who grew up in Pennsylvania and learned she had cancer caused by her mother’s exposure to Agent Orange, one of the many defoliants used by the U.S. during the war. The Hmong poets Soul Vang, Khaty Xiong, and Mai Der Vang are among the first in their culture to write full-length collections of poetry. This is a remarkable achievement, considering that the Hmong did not have a written language until the 1950s, even though the Hmong trace their roots back thousands of years to pre-dynastic China. So there is reason to hope, but there are also still so many more stories to be heard.

Coming to terms with the war has been a challenge for much of my life. Without the war, would I have come to the U.S.? For most Americans I’ve met, the war was a distant thing, or something to forget. They engaged with it at most through films like “Apocalypse Now,” “Full Metal Jacket,” and “Platoon.” Before he passed away, my father didn’t bring the war up much, except to note that he flew the news crew in to cover the release of the prisoners held at the Hanoi Hilton, and that he didn’t recognize John McCain at the time. Everyone had just been happy to be going home. A few years ago, I moved next door to a former POW who’d been a pilot shot down and held at the Hanoi Hilton, who’d flown bombing missions over Laos. Now he was retired in quiet Hemet, California. I was startled but didn’t know how to really have a conversation with him. And then one day, he moved away without even a goodbye. The other day, I was reminded by my mother that a cousin of mine was among the first pilots to pave the way for bombing Afghanistan after 9/11.

There should probably be a poem in there, somewhere. But for now, I just hope more of us will come forward and share our stories, so we can have a true conversation about who we are, who we’ve been, and what lessons we want the next generation to take away from all of this destruction.

—

Bryan Thao Worra is a Lao American writer. He holds over 20 awards for his work, including an NEA Fellowship in Literature, and he was a Cultural Olympian representing Laos during the 2012 London Summer Games. The author of six books, his work appears internationally in countries including Australia, Canada, Scotland, Germany, France, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, Korea, and Pakistan. He is the president of the Science Fiction Poetry Association, an international literary organization celebrating the poetry of the imaginative and the fantastic, and he is a founder of the National Lao American Writers Summit.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.