Remembering Robert Venturi, Philadelphia architect who gave ‘more’

Robert Venturi, one of the most influential design minds of the 20th century, passed away on Tuesday, September 18 at the age of 93, after battling Alzheimer’s disease.

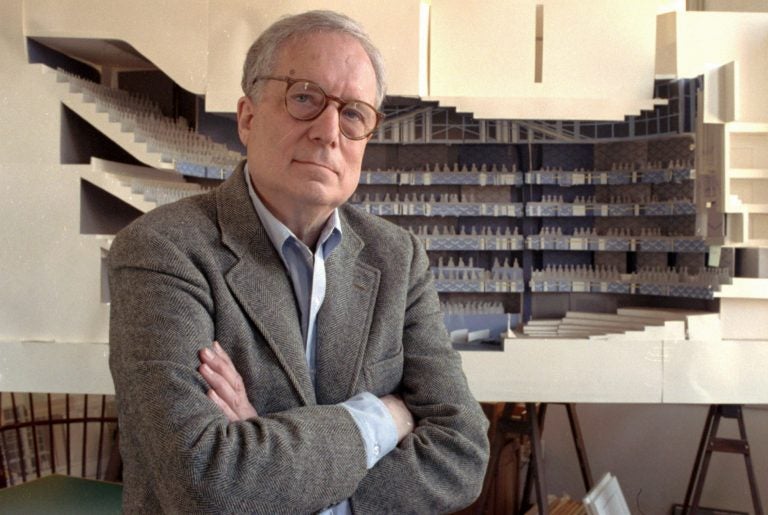

FILE - In this April 1991 file photo, architect Robert Venturi poses in his office in the Manayunk section of Philadelphia, with a model of a new hall for the Philadelphia Orchestra in background. Venturi, who turned austere modern design on its ear, ushering in postmodern complexity with the dictum "Less is a bore," has died. He was 93. His family released a statement on his firm’s website saying Venturi died at home in Philadelphia on Tuesday, Sept. 18, 2018, after a brief illness, and was surrounded by his wife and son. (AP Photo/George Widman, File)

This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

Robert Venturi, one of the most influential design minds of the 20th century, passed away on Tuesday, September 18 at the age of 93, after battling Alzheimer’s disease. In his passing, Philadelphia loses a native son whose work changed the course of architecture, and left an indelible imprint on his hometown – from the campuses of University of Pennsylvania and Drexel to residential architecture in Chestnut Hill and public spaces in Old City. His buildings and ideas live on, however, continuing to seriously challenge us with architecture that doesn’t take itself so seriously.

“I think Robert Venturi is one of the most important thinkers about modern culture of the 20th century… not just about architecture,” said David Brownlee, historian of modern architecture and Venturi scholar who first worked with Venturi in 1980. Venturi’s thinking, he said, drew from a much wider world and his influence was even more expansive.

Across more than 50 years of professional practice Venturi was best known for deflating Modernist architectural dogma: Instead of “Less is more,” Venturi countered, “Less is a bore.”

While Venturi preferred to see his own work on the Modernist continuum, others see it as the progenitor of architecture’s Post-Modern movement, recognizable for its exaggerated plays on traditional design elements. It’s a label he resisted.

“He never failed to appreciate intrinsic physical beauty of modernist objects, or their astonishing power as designs. But what he suggested did not work was their engagement with social reality,” Brownlee said. “It was a problem more broadly their failure to do well the thing that all great art should do, build a bridge to an audience and communicate with it.”

With his groundbreaking 1966 book, “Complexity and Contradiction,” Venturi was the vanguard for a design revolution, cracking open Modernism’s elitist, purist orthodoxies to make room for design that found “a conscious sense of the past.” Through that book and “Learning from Las Vegas” (1972), written with Denise Scott Brown and Steve Izenour, their conceptions of design stretch to include the kinds of everyday places we all experience. Think gas stations and roadside kitsch, South Street to the Vegas Strip.

“Complexity and Contradiction,” now 50 years old, couldn’t be more relevant. It talks about valuing diversity and difference, Brownlee noted, and calls for “working hard to bring them together in a productive unity. There is a social agenda in this work. He’s criticized for being crass. He didn’t love Las Vegas because people lost money there but because it taught lessons about how to connect with real people.”

For more than 50 years, he collaborated with Denise Scott Brown in one of American design’s great partnerships. Married in 1967, theirs was a shared life and practice that Scott Brown has described as “joint creativity.” Still, the male-centric architectural world tended to give Venturi the lion’s share of attention and praise. In 1991 Venturi was awarded the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honor, for his theoretical writings and design projects. After years snubbed as a sort of architectural Yoko Ono to his John Lennon, there is a movement afoot to honor Scott Brown more fully. In 2015, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were jointly awarded with the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal. The firm they shared, upon Venturi’s retirement in 2012, became VSBA and still operates from Manayunk.

Like Louis Kahn before him, Robert Venturi is one of the great architects Philadelphia has shared with the world. And some of his most important work is local. One of Venturi’s most significant works has been called one of the most influential buildings of the 20th century: The Vanna Venturi House (1964) in Chestnut Hill was designed for his mother, and launched him into early, albeit controversial fame.

Emily Cooperman is an architectural historian who co-authored the nomination which added the Vanna Venturi House to the city’s register of historic places.

“I remember distinctly the first time I walked into Mother’s House, I was amazed and astonished. And every time I’ve been in there since, that same sense has deepened.” The flatness of the front façade is like a child’s drawing of a house – a pitched roof, a chimney, a front door, presented in a balanced composition. But in Venturi’s hands, he turns all of its traditional and symbolic elements into something more intriguing: the pitched roof is incised, what you think is the chimney has a window in it, the front door is actually hidden and offset. Work your way into the house and you come to appreciate how confident and artistic and cozy the architecture actually is.

“You realize the house has this profound and wonderful sense of motion. It keeps you turning but you never feel as if you’re getting manipulated, you’re enticed,” Cooperman said.

“Mother’s House” and Guild House (1963), communal housing for low-income seniors on Spring Garden Street, are both Philadelphia pilgrimage sites for architects and students alike. His work had several calling cards – particularly the use of bold graphic elements and text. That was as true for early projects, like Guild House’s sign, as on later work, such as at the Curtis Institute’s Lenfest Hall (2011).

“Those buildings have so much going on, and they can be so polemic. Yet, you don’t feel like you’re being bludgeoned by them. They are not solely an expression of ego,” Cooperman said. He was better than that. “It sounds so anachronistic to say that he was charming and courtly. With Bob those qualities came off so human. But he was also so ironic and witty.”

Both buildings were the vanguard of what Venturi hoped would be a new kind of modernism – one unafraid of the joyful, often “messy vitality” of everyday life, while using the past as an influence.

Perhaps less appreciated is Venturi’s public work on sites like Franklin Court (1976, with John Rauch), which interprets what was Benjamin Franklin’s property, when all that remains is archaeology, with skeletal “ghost” buildings to evoke what might have once stood there. It is, very Venturi – as playful as it is refined.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.