Regulated tent cities for homeless pondered but improbable in Pa.

ListenBarriers include existing zoning laws and wide support for a permanent supportive housing-first model for reducing homelessness.

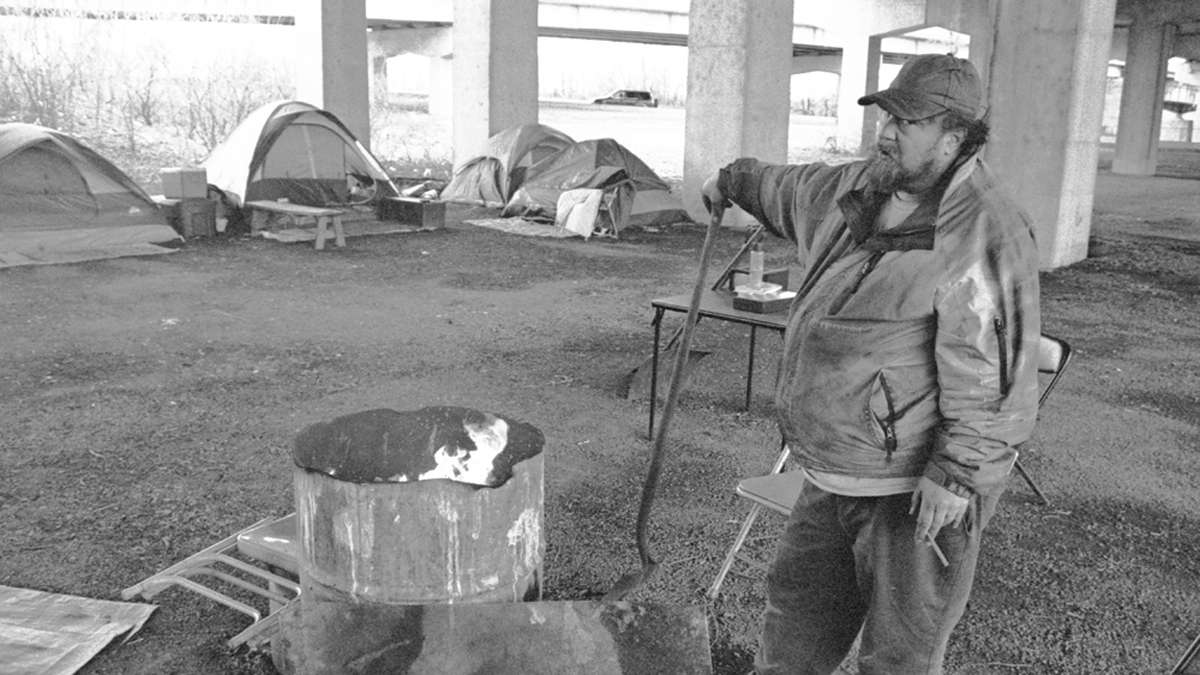

Frank Fairweather says poor health forced him to quit truck driving just shy of his 50th birthday. He kept a roof over his head for a while but then one roommate was jailed for a parole violation, and the other skipped town. Before he could find replacements, Fairweather fell behind on rent. He ended up joining several others camping under an interstate bridge near downtown Harrisburg.

Fairweather didn’t leave for three years, staying through winters and Tropical Storm Lee, until one night earlier this fall.

“The police showed up on Friday morning at 2 a.m.,” he said. “And I hear this officer’s voice, ‘Everybody out of their tents.’”

The cops got straight to the point, telling Fairweather, “you have three days to clear everything out, but you can’t sleep here.”

Why close the camp?

The camp closure in Harrisburg was unusual. Even in warmer weather, some other cities discourage and close down the camps.

But in Harrisburg, officials had ignored this encampment for most of the past decade, unless a public safety issue arose.

And that hadn’t happened in three or four years, despite its location in a highly visible spot beneath the Interstate 83 ramps at the city’s south end. Every day, thousands of drivers pass the site, just blocks from the Capitol complex.

Officials closed a camp that was bigger, but blocked from view, on an adjacent wooded site in 2010 at the request of its private owner.

This land, however, is public. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation owns the grassy, unobscured parcel. PennDOT Secretary Barry Schoch says he didn’t know about the encampment – or recall getting any complaints about it. The agency’s press secretary said the same.

It was complaints to local officials that prompted the closure.

Harrisburg Police Captain Colin Cleary, who coordinated the closure, says the city took action in response to complaints from residents of the Shipoke neighborhood.

That section of town is closest to the former campsite, but separated by a highway, sound wall and city street.

Keystone Crossroads reached out to several officeholders in the Shipoke Neighborhood Association, who directed the calls to Glen Dunbar.

Dunbar says he complained about encountering public urination, profanity-laced tirades, and empty liquor bottles during his daily walks through the park stretching five miles along the Susquehanna River near his home.

Dunbar’s neighborhood is called Shipoke, known for is brick sidewalks and well-kept houses just steps from the river.

“People here have worked very hard to restore the area, to take it from being a ghetto to being a very nice place to live,” Dunbar says. “Having a camp, an unauthorized camp, next door to the neighborhood. It moves things backwards rather than forwards.”

Dunbar also is a retired social worker, who teaches at Central Penn College and spent the bulk of his career as the state Department of Aging’s policy and research director. He says he’s sympathetic to the people living outside, and that the city wasn’t exactly doing the right thing by simply pretending the camp did not exist.

“They had everything there except sanitary facilities, and didn’t have electricity, of course. It had tents, it had picnic tables, it had a gas grill, had chairs, folding lawn chairs. I mean, it truly was a camp,” he says. “And that’s kinda my issue: If we’re going to allow camping in the city, then it ought to be done in accordance with some kind of zoning regulation.”

Just not there.

Dunbar suggests the former state hospital site on the outskirts of the city.

Local service providers and current and former elected officials can’t recall any serious consideration being given to establishing a camp there or anywhere else.

Neil Grover says the city might consider establishing zoning codes for the encampments, given the finite resources growing increasingly scarce for vulnerable populations.

But they probably wouldn’t act without getting clarity from state lawmakers first.

“There’s no place zoned for a camp in the city, so it would be a non-conforming use and any adjoining land owner could object,” Grover says. “I don’t think we’d be opposed to looking at it, but we’d probably, like in the state of Washington, have to go to the (legislature) and get their authority to act so … we’re not tied up in 20 years of litigation.”

Other approaches

Grover’s referring to a law passed four years ago by Washington state legislators, affirming local zoning for privately-run homeless encampments.

The statute took effect well after camps had become fixtures along the Puget Sound and in Seattle, where one site recently announced the launch of wireless Internet service there.

The city of Tacoma recently adopted a 14-page ordinance dictating basic requirements like permitting fee, renewal processes and timelines, and sanitation standards for bathing, drinking and eating accommodations.

Other rules provide for supportive services, like the requirement that campsites be proximate to bus routes with frequent service so residents can more easily interview for jobs and access support services beyond what’s available on-site.

But similar rules, and the formally-run sites they enable, remain rare.

Michael Stoops, Community Organizing Director for the National Coalition for the Homeless, cited camps in Seattle, Portland and St. Petersburg, Fla, as good models, although half of states have at least one encampment notable enough to make Wikipedia.

The Coalition frequently gets inquiries from people who want to establish homeless encampments elsewhere, but it’s rare they take action, he says.

“In Seattle, the tent cities move from church to church on a rotating basis, and that just hasn’t happened in any other community in the country,” Stoops says. “There has to be support.”

The Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania’s Policy Director Cindy Daley says she doubts there’d be enough in the Commonwealth.

In addition to the state’s conservative bent, most fair housing and homeless in Pennsylvania– and nationally– support a housing-first model.

“If we put our focus on establishing more tent cities, that takes away from establishing more affordable housing,” Daley says. “Assuming we have limited resources, where do we want to put them?”

Daley also says research shows people tackle the issues contributing to their homelessness fastest when they’re first placed in permanent-supportive housing.

That’s one reason behind the National Alliance to End Homelessness promoting the housing first-model – and not camps, according to the alliance’s vice-president of policy & programs Steve Berg.

The housing-first method also drives the Alliance’s Ten-Year Plan to End Homelessness framework, adopted by many cities and regional service providers.

Allentown Mayor Ed Pawlowski pushed to launch his city’s 10-year plan in 2006, during his first term. He says it’s the local government’s responsibility to lead an effort to increase affordable housing, social services and job opportunities.

But even if the will and resources are there, it takes time to mobilize those efforts and build or rehab housing.

What about camps, in the meantime?

Pawlowski says no.

“Listen, I come from a family of social workers,” he starts to explain.

What about with supportive services on-site?

Still, no, Pawloski says.

“It doesn’t promote that healing, and it doesn’t promote that sense of moving from, transitioning from the homeless scenario that they’re in, or getting them help they need to transition out of that homeless scenario,” he says.

Allentown has systematically closed at least four encampments since 2008, as dictated by the city’s 10-year plan.

The process, which has sparked controversy and opposition from some advocates and homeless residents, aims to get people living in the camp into supportive housing.

It involves multiple agencies and entails multiple steps during the two weeks leading up to the camp’s formal “close date”; after that, people found at the former campsite would be charged with trespassing.

Other cities, including San Jose, have taken similar approaches.

Harrisburg’s 10-year plan doesn’t mention camps, let alone how to address them.

The city also carried out the closure without engaging social service providers. This, despite the fact that the head of Capital-Area Coalition on Homelessness, Bryan Davis, is also the Harrisburg Redevelopment Authority’s executive director.

CACH is the umbrella organization for service providers in and around Harrisburg, including Bethesda Mission, which runs a homeless shelter in the city.

“We could have just asked the people to leave,” says Bethesda Mission Executive Director Chuck Wingate. “Instead, people were frightened, and you have the potential for danger and mistakes. … Not to mention, the expense of sending police officers out.”

Still, Wingate says, police acted professionally, by most accounts. When asked about leaving out advocates, Cleary says only that it was an oversight.

What’s next?

Davis says there aren’t plans to more distinctly set out procedures in the plan because “our plan isn’t to shut down camps.”

After the I-83 camp closure, Davis says, the city gave its “pledge and promise” to engage CACH and its partners in the future.

Officials have since reached out after learning the owner of a heavily thicketed property has plans to clear it.

Davis says outreach workers canvassed that area to find out whether anyone is camping there.

They are, and will have to move, though Davis stresses the property owner hasn’t provided a timeframe yet.

The clearing might well send Frank Fairweather searching for another spot.

Fairweather says he won’t go to a shelter – he hasn’t gone during past winters and doesn’t plan to in the coming cold months.

Fairweather spoke to Keystone Crossroads in the spot where he’s pitched his tent since the interstate bridge site was closed.

He cried at times during his interview.

Estranged from his wife and daughters living in Las Vegas and thousands of miles from his childhood home of Sacramento, Fairweather refers to the people he camped with in Harrisburg as his family.

But he acknowledges police “had every right” to force them from their former home under the I-83 bridge.

Fairweather and the other camp residents scattered, each finding new spots in or near the city.

His new, more secluded spot isn’t far from downtown.

But the trip there is more significant for Fairweather because he suffers from neuropathy, a condition that’s swollen his ankles and legs and makes it painful to walk.

The trek isn’t optional, though, not if Fairweather wants to eat, take a shower, or get mail.

“The homeless, they have a lot for us here,” he says, ticking off the schedule and location of meals served by churches and non-profits in the city.

As far as whether Fairfield’s old camp will form again, Police Captain Cleary says it’s not just possible. It’s inevitable.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.