Rain, rain flows away, no longer puddles at Malcolm X Park

As happens on many blocks around the city, heavy rains used to turn the southeast corner of Malcolm X Memorial Park in West Philadelphia into a deep puddle.

Gregorio Pac Cojulun (left), and Dan Schupsky, an outreach specialist, stroll along one of the new sidewalks. (Meir Rinde/PlanPhilly)

This story originally appeared on PlanPhilly.

—

As happens on many blocks around the city, heavy rains used to turn the southeast corner of Malcolm X Memorial Park in West Philadelphia into a deep puddle. Water flowed down from the surrounding streets and collected around a sewer drain often blocked by leaves, mud and trash, or just too full to take in any more.

“When it rains in the summertime, you have those thunderstorms come out. At 51st and Larchwood, it was like a swimming pool,” said Gregorio Pac Cojulun, longtime president of the group Friends of Malcolm X Park. “Water used to rise all the way up to the entrance of the park. It was kind of crazy.”

“But they got it now, and it seems to be doing good, so far.”

That’s a side benefit, he said, of a Philadelphia Water Department environmental project aimed at improving natural infiltration of stormwater into the ground. After several years of planning and months of construction, the park has sections of new sidewalk on three sides and 29 new street trees, as well as new underground plumbing. Rainwater runs through inlets into buried tree trenches under the sidewalk, rather than pooling in the road or overloading the sewers.

For Cojulun and the many others who come to Malcolm X Park to enjoy its playgrounds, pavilion, and popular jazz concert series, the $620,000 project is just the latest improvement to a public space that has become a vital resource for the neighborhood since its revitalization in the late 1990s. A ribbon-cutting ceremony was planned for Thursday, Aug. 2, to unveil the new trees and sidewalks.

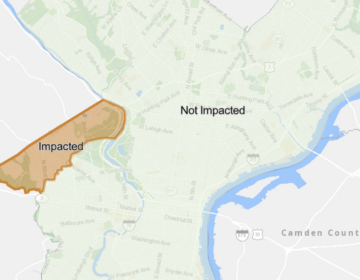

For the Water Department, the construction advances a long-term effort to prevent sewer overflows and keep polluted water out of the city’s rivers and residents’ basements. It also represents an expansion of the department’s Soak It Up Adoption initiative, a nine-year-old grant program that brings in community organizations as partners in maintaining green-stormwater infrastructure and educating residents about why it’s there.

The partner for Malcolm X Park is Greensgrow West, a branch of the Kensington-based urban-gardening nonprofit. Greensgrow already helps monitor stormwater infrastructure at four schools and a recreation center, removing waste and alerting the city to damage or other problems with the trees or the trenches.

“This partnership program is kind of showing people how important these things are, picking up the trash and making sure they’re functioning properly, and has a really important education piece, so people understand that this infrastructure is really important to all of our health as residents of this city,” said Ryan Kuck, Greensgrow’s executive director.

“We love Malcolm X Park,” Kuck said. “We are excited about all the changes and hope it continues to be a wonderful place for the neighborhood.”

Other organizations monitoring Soak It Up Adoption sites in West Philadelphia include Southwest CDC, Urban Tree Connection, and Centennial Parkside CDC, said Dan Schupsky, an outreach specialist who is a contractor for the Water Department. Citywide, 16 partner groups monitor about 110 sites. Partners receive annual grants of about $1,500 to $6,500, depending on the number of sites and amount of work they take on.

The funds go to buy equipment like trash-grabbers, brooms, gloves, dustpans, and safety vests, and to pay for public-engagement activities like meetings, event tabling, email newsletters, and social-media posting, Schupsky said. Though the partners may employ volunteers or their own paid staff, some use the grants to pay senior citizens, young people, or other community members to work as site monitors for a few hours a week.

Soak It Up Adoption’s annual budget is about $70,000, Schupsky said. In the first half of 2018, participating groups picked up 21 tons of trash and engaged with more than 1,600 residents.

“To do all that for $70,000 is really impressive, and it says a lot about how hard the partners work,” he said. “It’s very grass roots, a very boots-on-the-ground kind of organization.”

The Water Department views Greensgrow and the other organizations as extensions of itself, serving as ambassadors of its Green City, Clean Waters program, Schupsky said. “They’re working to help keep their hyper-local environment looking really good and that stormwater infrastructure functional. One thing I say to them is, ‘You’re basically part of the Clean Water Act, sort of. You can say that you’re helping with this really big problem of these CSOs, these combined sewer overflows.’ As long as the green-stormwater infrastructure is working well, they’re helping reduce the amount of polluted water that’s going out to our local waterways,” he said.

Kuck said Greensgrow will eventually encourage Friends of Malcolm X Park to join Soak It Up Adoption itself and begin monitoring the tree trenches, if the group’s volunteers are interested.

That came as a surprise to Cojulun. “I’ve got enough trees in my park to take care of, but they’re welcome to come to one of our meetings, talk to me, talk to my group and see what they say,” he said. “It all depends on my group — whatever they say, goes.”

The tree-trench installation at Malcolm X Park is one of more than 1,000 projects the Water Department has sponsored as part of Green City, Clean Waters.

Established in 2011 to comply with a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency mandate to reduce sewer overflows, Green City, Clean Waters deploys tree trenches, planted curb bump-outs, sidewalk planters, permeable pavement, green roofs, rain gardens, and rain barrels to slow the movement of stormwater into the sewer or keep it out entirely. The department also performs traditional sewer-infrastructure upgrades.

The alternative would have been to spend nearly $10 billion to build a 34-foot diameter, 30-mile-long tunnel under the Delaware River that would have stored sewer overflows and pumped them to wastewater plants for treatment after storms, according to Howard Neukrug, who was the city’s water commissioner when Green City was launched.

More than 40 of the green projects are at parks, and several more are in the works, Schupsky said. They include an extensive project under construction at Cobbs Creek Park that will include tree trenches, bump-outs, a stormwater basin, and rain gardens. Projects at Carroll Park and at Elmwood Park in Southwest Philadelphia are in the design phase, he said.

The young plantings around the perimeter of Malcolm X Park join dozens of older trees that shade the 6-acre site and create a tall burst of green amid the neighborhood’s tightly packed rowhouses, churches, and small businesses.

On a walk around the park earlier this week, Cojulun pointed out the improvements he has helped shepherd over the decades. With funds and assistance from the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Citizens Bank, and the Parks and Recreation Department, Friends of Malcolm X Park was able to clear dead trees and plant new ones, reroute walking paths, build a playground and tot lot, and put in new benches and the lighted pavilion. Restrooms are in a small building painted with a mural of Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz.

Previously called Black Oak Park, it was popular and well-used in the 1960s, but by the 1990s drug dealers and prostitutes moved in and families no longer felt comfortable there, Cojulun said. The park’s name changed in 1993, neighbors set up the Friends group, renovations began, and the park was rededicated in 2000.

Now, the park bustles with noisy crowds of children from several day-care programs in the morning and hosts a wide variety of other activities, he said — weddings, birthday parties, church services, Thursday night jazz shows, dance performances, movie screenings, the occasional gubernatorial campaign event, and much more. As Cojulun walked across the park, a father and son bicycled in circles around the pavilion, and several benches were full of people hanging out.

“It just grew and grew and grew. It’s probably one of the most sought-after parks in the city of Philadelphia,” he said. “We try to help the children out. That’s our goal, to make sure they have a place to play, safe and sound.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.