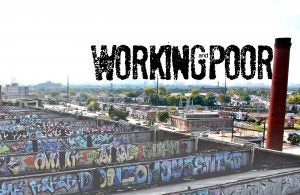

Quandary over reversing Philadelphia’s long, slow slide from self-sustenance to chronic poverty

Listen 5:41

In this Oct. 1

In the middle of Westmoreland Street, just past North Uber, is a deep red row home with steep steps.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Dolores Harris and her family lived here before moving around the corner and, eventually, out of North Philadelphia completely.

Her mother and father slept there, but also a grandmother, a grandfather, and two aunts.

“It was a lot of us in that house,” said Harris, grinning during a recent visit to the block.

There was also the family beyond her living room — the neighborhood. Harris said people looked out for one another, even watched big boxing matches together.

Only a couple houses had televisions then.

“Joe Louis was fighting, and everybody was on the steps and in our house,” said Harris.

Things changed as 1960 crept closer. A lot of the factories that dotted the neighborhood were either on their way out or gone, including several within walking distance of Harris’ house on Westmoreland.

Bunting Glider. Exide Battery. The Hood Company.

Soon, there were fewer homeowners. More renters. The jobs weren’t there to keep people around long.

“It just like one drops off, and then another drops off, and one day you look up … and a lot of people that I knew were not there,” said Harris.

‘Workshop of the World’ shuttered

Harris’ story isn’t unique. It’s part of why Philadelphia has the dubious distinction of being the poorest big city in the country.

For decades following the Civil War, Philadelphia was known as the “Workshop of the World.” The city manufactured hundreds of products — and a lot of textiles.

Factory jobs sustained many neighborhoods like Harris’ in North Philadelphia. Many workers didn’t need a high school education to be on the payroll.

“One needed a strong back or dexterous fingers, or just a willingness to stand on your feet all day long and do tedious work. If you did that, for the most part, people got a living wage and there was some job stability,” said Judith Levine, an associate professor at Temple University who studies poverty.

As factories packed up for bigger, cheaper spaces in the suburbs and overseas, neighborhoods started decaying, some as early as the mid-1920s. And many have just never bounced back, in part, because all of those well-paying factory jobs never came back.

Instead, there are now lower-paying service industry jobs, many of which are part time or temporary. And the city’s biggest industries — “eds and meds” — require college educations.

“And Philadelphia, unfortunately, has an education problem. Our educational system is in disarray, it’s underfunded and our population is not highly educated,” said Levine.

Only 26 percent of Philadelphians have a college degree. That’s below the national average, as well as other impoverished cities such as Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Boston.

But there are other factors. “White flight” did a lot of damage too by concentrating poverty in the city.

Robert Chaskin, who teaches classes on urban poverty at the University of Chicago, said some of that phenomenon was fueled by the real estate industry.

In Philadelphia and other big cities, Realtors employed “scare tactics” to drive out white working-class families as more and more African-Americans moved from the rural South to the North during the Great Migration.

The pitch in a nutshell: sell before property values start plummeting.

“[Realtors] were able to purchase these properties at relatively low prices and turn around and rent them, often breaking them into smaller units, often at a premium to the African-Americans moving in,” said Chaskin.

At the same time, some banks made it difficult or impossible for African-Americans living in certain sections to get loans, mortgages, and other financial services.

Redlining was officially outlawed in the 1970s, but its impact continues with housing segregation, as well as an inability to benefit from the wealth gained through real estate appreciation.

Today, roughly one-quarter of Philadelphians live in poverty. And about half of them are living in deep poverty, defined as earning less than half of the federal poverty line.

For a single parent with two children, that was around $10,000 a year in 2014, the latest census data.

These figures are bad, but just a few years ago, they were actually worse. At the height of the Great Recession, the city’s poverty rate was 28 percent.

What changed?

Temple’s Levine said the city’s population has grown steadily since then — every year. And a lot of the people moving in aren’t living in poverty. Many are young professionals.

“They are diluting the poverty rate because they’re part of the denominator of the population of the city and they’re not part of the numerator of the people in the people of poverty,” said Levine.

In other words, Philadelphia still has roughly the same number of people living in poverty.

Mitchell Little who heads Shared Prosperity, the city’s anti-poverty program started under former Mayor Michael Nutter, remains hopeful.

“Momentum is growing. I think the political will is there. And I think as we in the health and human services cabinet, as we start to gel as a cabinet, I think you’ll see a new synergy there that will help move some of those other metrics forward,” said Little.

Shared Prosperity runs out of the Mayor’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity, but works closely with the Department of Health, Behavioral Health, and the newly named Office of Homeless Services, formerly the Office of Supportive Housing.

The program has had some success, mostly setting up BenePhilly Centers, where people having trouble getting by can find out if they’re eligible for state and federally sponsored programs.

Levine also sees some silver linings. She’s encouraged by Mayor Jim Kenney’s commitment to addressing poverty.

Kenney successfully pushed for the city to enact a sweetened beverage tax on distributors to help fund his vision for universal pre-K, “community schools,” and upgraded parks and recreation centers.

But overall, Levine is less optimistic than Little.

While the international spotlight shines on Philadelphia for the Democratic National Convention, she predicts the city will be dealing with the same issues 10, even 20 years from now, in part, because the cycle of poverty can take multiple generations to break, and she doesn’t see enough being done to shrink it.

Moving up, not out

Under the late-morning sun, Harris briefly looked over her old house before heading toward her Dodge Caravan to return to her new home in Chestnut Hill.

Tucked into the childhood nostalgia is a twinge of sadness and guilt — guilt that she left 19th and Westmoreland. Guilt that so many others did too.

“We keep running. Where are we running? At some point, we’re not going to be able to run anymore,” said Harris. “If we have a problem here, did anyone stop to think about how to fix this problem? Then maybe we won’t have to run.”

But what Harris calls running is often called “moving up,” and one of Philadelphia’s biggest challenges is to help people out of poverty while also working to ensure longtime residents in gentrifying neighborhoods aren’t pushed out. So people can move up without feeling they have to move out.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.