Puff, Puff, Pass: Philly Council to debate banning hookah bars in most of the city

Neighborhood groups across the Northeast are on a campaign to shut down hookah bars they see as disruptive to their community.

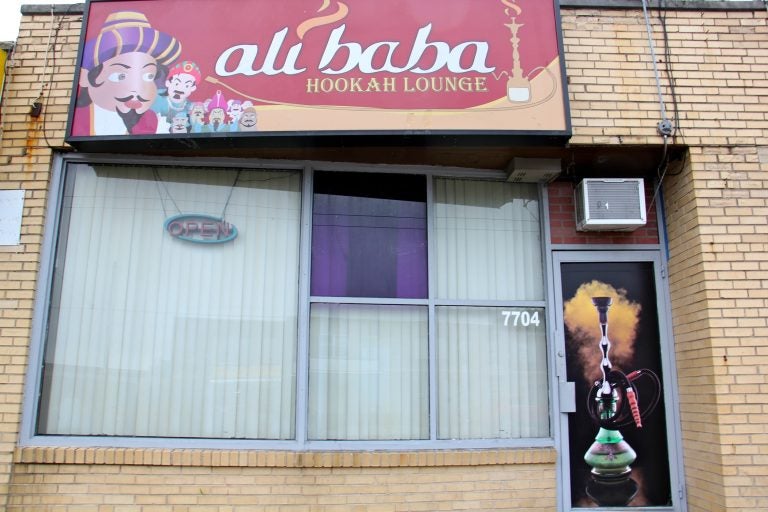

Ali Baba Hookah Lounge on Castor Avenue in Northeast Philadelphia. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Castor Avenue cuts through the middle of lower Northeast Philadelphia. It’s a broad, busy corridor lined with small businesses reflective of the changing demographics of some of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods.

On Castor’s 7700 block, Ali Baba Hookah Lounge wedges between a State Farm Insurance office and a Brazillian grocer.

Earlier this year, the popular evening hangout closed unexpectedly. On a hot August day, it was sealed up tight with the shades drawn. The sign on the front said, “CEASE OPERATIONS.” In scrawled long-hand, a city inspector explained that the business needed a certificate of occupancy and a food license.

Ali Baba’s longtime manager, Mohammed Amer, said the hookah lounge’s troubles were a misunderstanding.

“When the owner, he go to the city to make his license, no one knew about hookah,” said Amer, who moved to Philadelphia seven years ago from Alexandria, Egypt. “Your zoning is restaurant, this is hookah. Where is the restaurant?”

Neighborhood groups across the Northeast are on a campaign to shut down businesses like his, where people gather to smoke tobacco products from a shared water pipe.

A July meeting of the Rhawnhurst Civic Association drew dozens of neighborhood residents eager to talk about blocking one neighborhood hookah spot from obtaining its permits. The complaints were many, and they are getting results.

The civic association’s membership voted unanimously four times against Castor Avenue hookah bar owners seeking permits. Complaints about fights, loud music, and parking resulted in inspections that found violations of zoning and liquor laws.

At least three other hookah bars in the Northeast were shut down by the city over similar issues in 2019.

And now, a bill slated for consideration in City Council this fall aims to make it harder to open a hookah establishment in much of the city.

The proposed legislation, introduced by Northeast Philadelphia Councilmember Bobby Henon on the last day of the spring session, would add “smoking lounges” to the zoning code. The bill clarifies the kind of permit hookah or cigar bars need to operate, which could simplify things for operators.

But there is another provision that has broader implications for any smoking lounges, a category that includes places for vaping or smoking of any tobacco product. The regulation would not allow these businesses to open anywhere but the most permissive zoning districts in the city, which are clustered downtown and tend to command higher rents.

That means that if Amer wanted to open another hookah bar in his Northeast Philly neighborhood, he would have to meet with neighborhood groups and solicit their support, then hire a zoning lawyer and go to the city’s Zoning Board of Adjustment to secure a variance or special exception to open. Without neighborhood support, a business’s petition to open is more likely to be blocked.

Henon frames the de-facto neighborhood ban as a win for public safety and community oversight.

“We’ve had somebody shot, we’ve had somebody run over, we’ve had numerous police incidents at every single one of them,” said Henon in an interview with PlanPhilly. “Do you let this run rampant and infest and kind of spawn all over the city of Philadelphia?”

On Castor Avenue, Amer sees it differently.

“A lot of the neighborhood are racist,” Amer said. “Why you guys don’t support hookah bars, but you do support bars? Hookah is like cigarette — you still have your mind, you still have your brain, you can control yourself. It’s not drugs. At bars, it’s different. One shot, two shots — after that, you drive your car and can make accident.”

‘The minute you mention hookah, its drugs, alcohol, and Al Qaeda’

Amer said that although he does not drink himself, he allows people to consume wine and beer (not liquor) on the premises when Ali Baba is open. He says a BYO policy ensures he can attract an American clientele, not just fellow immigrants from Middle Eastern and African nations.

Ali Baba Lounge stayed closed for much of the year because the owner did not have a certificate of occupancy, zoning permit, or a food license. Although they obtained zoning permits, they reopened without a certificate of occupancy or food license and the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections ordered them to cease operation again. On a visit in early September, the hookah bar was open again.

Some neighbors in the Northeast say the backlash is a heavy-handed overreaction.

“We have nuisance bars, so are they just going to ban all bars now,” asked Lee Horne, a Democratic Committeeman and Rhawnhurst resident. Why zone out hookah bars, he asks, when the city already has the tools to shut down illegitimate or dangerous businesses?

Those tools worked earlier this year when, in Holme Circle, the D (Dollars) Lounge was closed down after city officials found the owners had connected three properties illegally, knocking out the walls without the proper permits.

Another spot that was closed, Bucky’s Cafe, lacked a food license and other necessary permits.

The Hush Social Club, on Frankford Avenue, not far from the Mayfair Diner, sold liquor without a license. It closed after a patron got shot 17 times outside and another was run over in a vehicular assault.

But Horne said the opposition to hookah in neighborhoods like Rhawnhurst lumps in the good businesses with the nuisances.

“The neighborhood is generally against all hookah bars,” said Horne. “The minute you mention hookah, its drugs, alcohol, and Al Qaeda.”

Horne attributes some of the backlash against hookah bars to growing pains as the area, a magnet for immigrants, changes. The census tracts that comprise Rhawnhurst are 66% white, according to American Community Survey data from 2017, compared to 96% white in 1990. In the past 27 years, the foreign born population more than doubled and now comprises almost 30% of the neighborhood.

Some of the newer arrivals are from predominantly Muslim nations in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.

“Their hookah lounge, to them, is like the Jewish deli to me,” said Horne, at a July Rhawnhurst Civic Association meeting where a hookah bar received a resounding “no” vote. “It’s a place to hangout, have a sandwich, and talk about family. For the Islamic man, that’s a hookah lounge. The problem is the good ones get a bad rap from the bad ones.”

Akira Rodriguez of the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Regional and City Planning, says that the bill and the language Henon’s office used to promote it on social media point to a pattern of exclusionary zoning.

“Hookah smoking, in some instances, is provided as a basis to promote nightclub-like businesses that are out of character and disruptive to the adjacent community,” reads Henon’s Facebook post about the bill’s introduction.

“These terms of ‘out of character,’ and ‘disruptive to the community’ are consistent with often racialized and classed arguments for exclusionary zoning,” said Rodriguez in an email.

Henon disagrees. He says his legislation won’t hurt those who are trying to operate legitimate businesses.

“This isn’t for the good actors, it’s for the bad actors,” said Henon. “I’m sure there are legitimate hookah lounges in the city of Philadelphia, and they are going to be fine. This is for the [hookah bars] I’m seeing pop up throughout our neighborhoods by-right with no communication, without any regard for public safety and quality of life.”

One thing Amer, Henon, and other city officials agree on is that a definition for hookah bars in the zoning code would make operating businesses easier.

“There isn’t a use category for smoking establishments and so some of these businesses are trying to get a permit under what they think might be close,” said Karen Guss, L&I spokesperson.“Then when it turns out that they aren’t in fact a café, now they have a zoning violation.”

But the bill’s other provision, effectively limiting by-right “smoking lounges” to Center City, still leaves Amer, Horne, and other observers troubled.

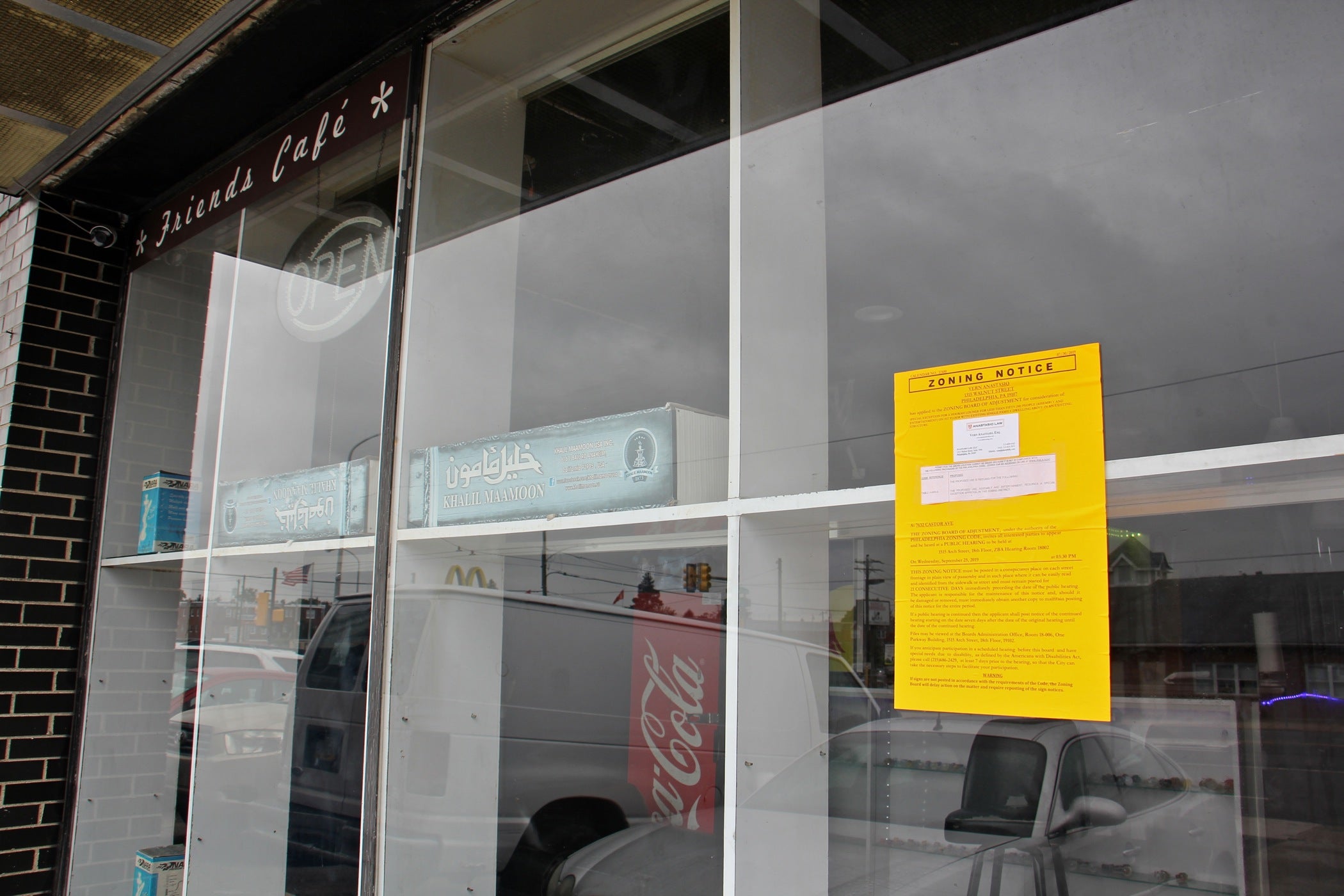

Meanwhile, at the July meeting of the Rhawnhurst Civic Association, a packed house voted against supporting Friend’s Cafe hookah lounge’s zoning application. They are likely to face neighborhood opponents when they go before the zoning board in September. Republican Councilman Brian O’Neill offered to reimburse the costs of parking and rideshare for neighbors who want to attend the zoning board hearing downtown.

Kimberley Schultz Quinn is a Rhawnhurst resident who says she’s been personally disrespected by the lounge’s patrons.

“It brings in a very negative element, especially because its a BYO,” said Schultz Quinn, who lives nearby. “I think this is basically like an underground bar. Almost like a speakeasy, that’s the vibe I get from it.”

Neither Friend’s Cafe, nor their lawyer, Vern Anastasio, returned numerous phone calls for comment. Staffers inside Friend’s Cafe also declined to talk to a reporter.

Henon’s bill will be considered by the full City Council after the body reconvenes on Sept. 12.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.