Protest pop: On creativity as resistance

As I embark on my third solo album, I find myself in a culture that increasingly sells its soul, in the name of money, in the name of sex.

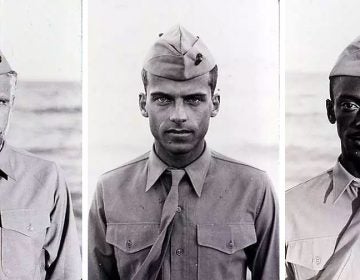

Andrew Mars is the lead writer and vocalist of Settled Arrows. (Dustyn Christofes)

Philadelphia favorite son and Grammy Award-winner Questlove has published “Creative Quest,” a collection of stories and lessons about living one’s best creative life. In this spirit, Speak Easy has asked Philadelphia artists to share stories of their own creative quests.

—

For the longest time, I thought music was dead. “American Idol” had turned art into a competitive sport, and increasingly the mainstream seemed to be the only option. All genres were blending into one super-mega genre of stadium sound that seemed to be formed by committee and focus-grouped into existence.

I sank into a huge depression. I stopped singing. I didn’t play piano. I no longer saw the point. I had devoted my life to music, but suddenly the joy it gave me just stopped. Music had once been the place that I went to feel limitless. It was my healing balm. But I’d suddenly lost the thread. Studying at a classical conservatory had turned music into a place I went to judge my limitations. I could no longer see my worth or why music even existed.

Artists who once were bastions of alternative culture now seemed to be capitalist marketing pawns whose music was a commercial for their clothing lines. I couldn’t see my place in this world. So I stopped. It was 2005. I was a teenager.

Looking back, I now see that I was simply growing, and my creativity was waiting to bloom in other ways. I had been studying opera and was experimenting in vocal improvisation, but I quit music school. I wanted to quit school altogether, but my family wanted me to get a degree. So in an act of rebellion (against them? against myself?), I decided to become an anthropologist.

I devoured writings on religion, national identity, migration, the history of humans and our symbols, language, the culture of meetings in corporate settings, death and dying, aging in various societies. Worlds of understanding suddenly opened up to me. I thought I was going to change the world of academic thought using the methods of postmodern anthropology as social critique.

Then I graduated. I had no money. Still naive and full of hubris, I looked for jobs as a cultural critic or a consultant to corporate culture. Nothing happened. So I did what was probably inevitable for a young idealist of my income bracket: I got a job at a chain restaurant.

I still wasn’t singing. I was still bitter about music and the state of American culture. I served fried chicken to huge families in a conservative Connecticut town. I wore a uniform and had meetings with middle-level managers from the corporate office about the best way to sell our new microwaveable desserts. They reprimanded me when I didn’t use the right catchphrases. I experienced homophobia — often — but I didn’t leave the job. I just moaned about it. My depression was solidifying.

I decided to become a massage therapist and enrolled in a program to study the body and how to heal it. I was convinced that it was just a matter of time before alternative medicine would be covered by insurance, and I would be working alongside doctors and respected as a health care provider. My family thought I was lost. They just shook their heads in disbelief at my choices.

Then I fell in love and moved to Philadelphia.

I fell out of love and stayed in Philadelphia.

I threw myself into my massage career. I found queer community for the first time. Miraculously, I began to sing again … at karaoke. Karaoke was my saving grace. I could sing whatever I wanted, without judgments. There was no jury to grade my vowel placement. There were, however, new friends who loved the same songs as me. These were other former artists struggling with the same depressions. These were social theorists and people working in cultural institutions who also wanted to change the world.

I was coming out of my depression and realizing I wasn’t so isolated. I began singing again, every day. I found a voice teacher. Suddenly inspiration flowed again. What had seemed like detours away from my dream had led me back to my lifelong passion: music.

Almost miraculously, I met other classically trained musicians who improvised like me. We started an ensemble. I was going to bring punk rock into classical music, to bring the creative process into the mainstream through live improvisation, to revolutionize the subjects that could be sung about in a classical style. With this group, I sang at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, improvised songs on the radio using news stories, performed at arts festivals.

This led to a job co-writing a full-length ballet for a local organization. This led to my voice being reviewed by the New York Times. I was hired to work on a research project studying collective creative process with Pauline Oliveros, a luminary who developed the deep listening method, which combines meditation and self-awareness into an improvisational form.

Then, as they do, people began dying. I lost eight family members and close friends, injured myself, was uninsured and lived in pain for years. Payments arrived late and started to dwindle. The group I had founded folded. I was back to a deep depression, and I stopped singing — again. But this time, in my state of duress, music began to come to me. Almost against my will, whole songs were showing up. The creative process was truly saving my life. It was 2013.

My studies and life experiences, my failures, my literal pain — all of this was giving me insight. I decided that if the mainstream was increasingly only interested in adolescents singing about sex, I would be the alternative. I would bring intellect back to pop music. This is the state I was in when I wrote my first solo collection of music, “Public Privacy.” I was back to my teenage idea of using anthropological methods to critique the current state of culture and myself. I wrote songs about dating apps, estrangement, disillusionment, forgiveness, the way people communicate online. “Public Privacy” was received very well, and I was given the opportunity to create a second album.

This was around the time of the murders of Philando Castile, Alton Sterling and of the most recent presidential election cycle. My disenfranchisement from American culture was only growing. Where was the way out of vampire capitalism, the trampling of human rights, bigotry, and institutionalized hatred?

So with my band, I began creating my sophomore album: “Innocence // The Fall of the Fool.” I wrote songs of protest. I wrote a concept album using the principles of alchemy, the symbolism of tarot, and the type of language that I wish I could hear at protests.

Where do we go from here?

What is the root of all this fear?

For me, creativity is a radical act. This word comes from the Latin radix, meaning “to return to the root.” This has been my experience. All roads have led me back here.

As I embark on my third solo album, I find myself in a culture that increasingly sells its soul, in the name of money, in the name of sex. My commitment is to art for its own sake. More than ever, artists need to fight for a place where the imagination can flourish, where people can find nourishment and recharge away from the lies and pace of modernity. More than ever, artists need to commit to telling the untold stories. My art form is music. More than ever, musicians need to create a space for humans to sit quietly and simply listen. Now that’s radical.

—

Andrew Mars is the lead writer and vocalist of Settled Arrows. Their music can be found at www.settledarrows.bandcamp.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.