Princeton exhibit highlights the love/hate relationship we have with Charles Lindbergh

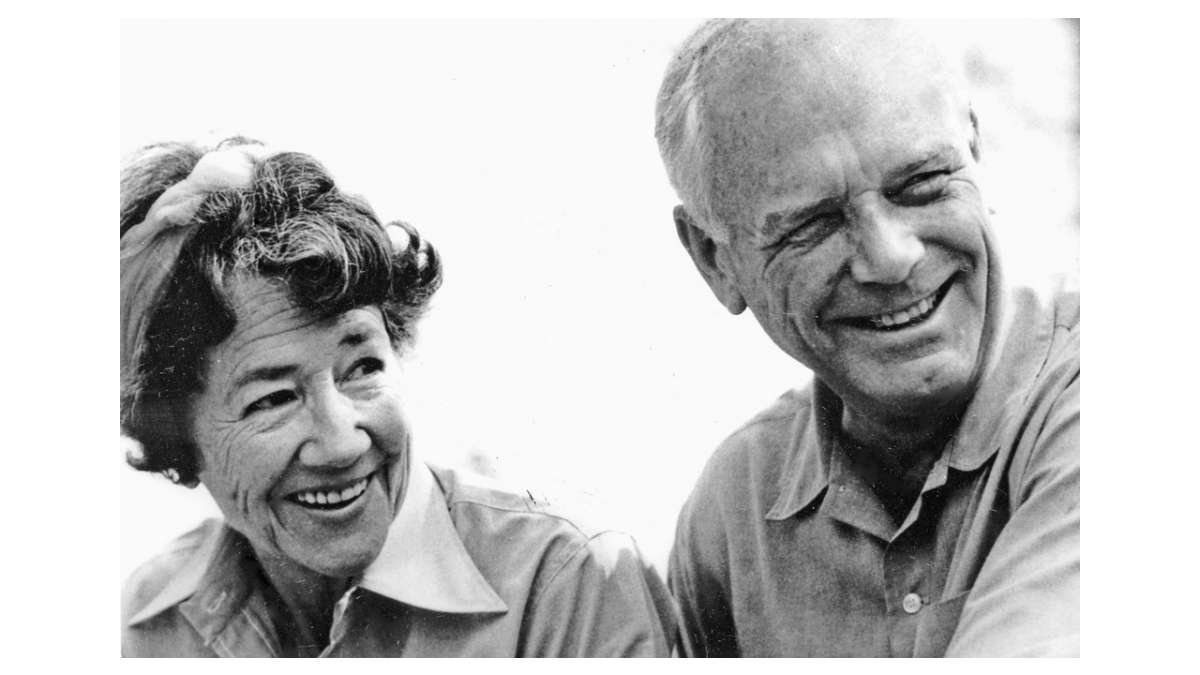

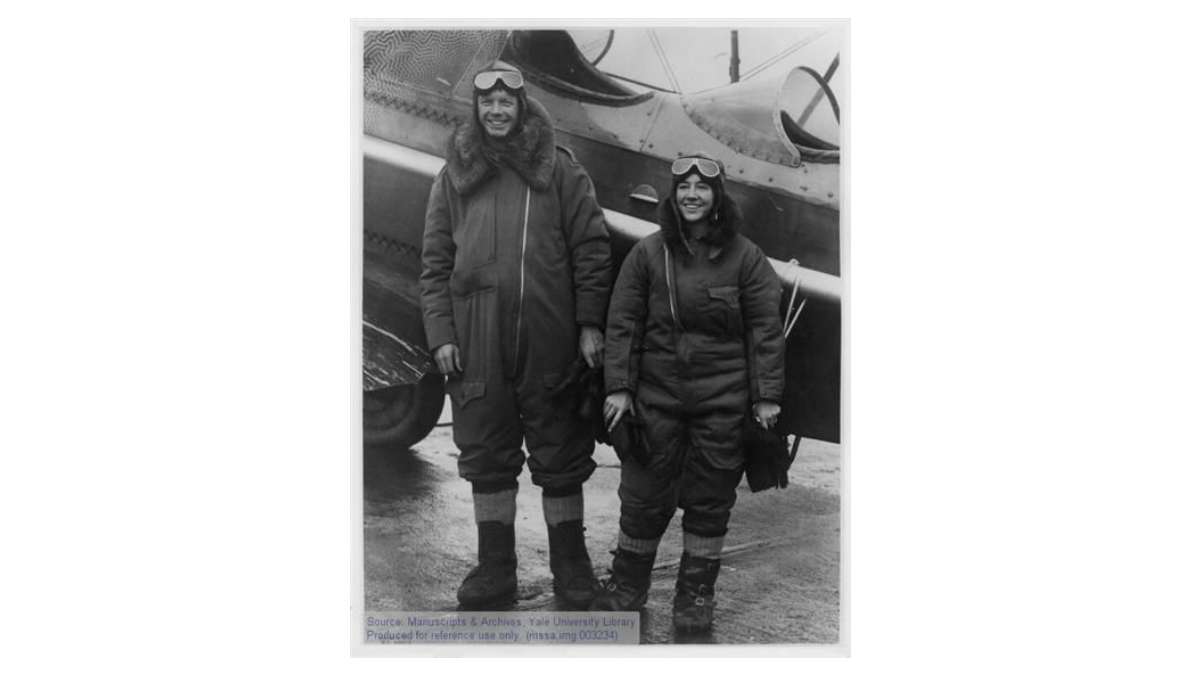

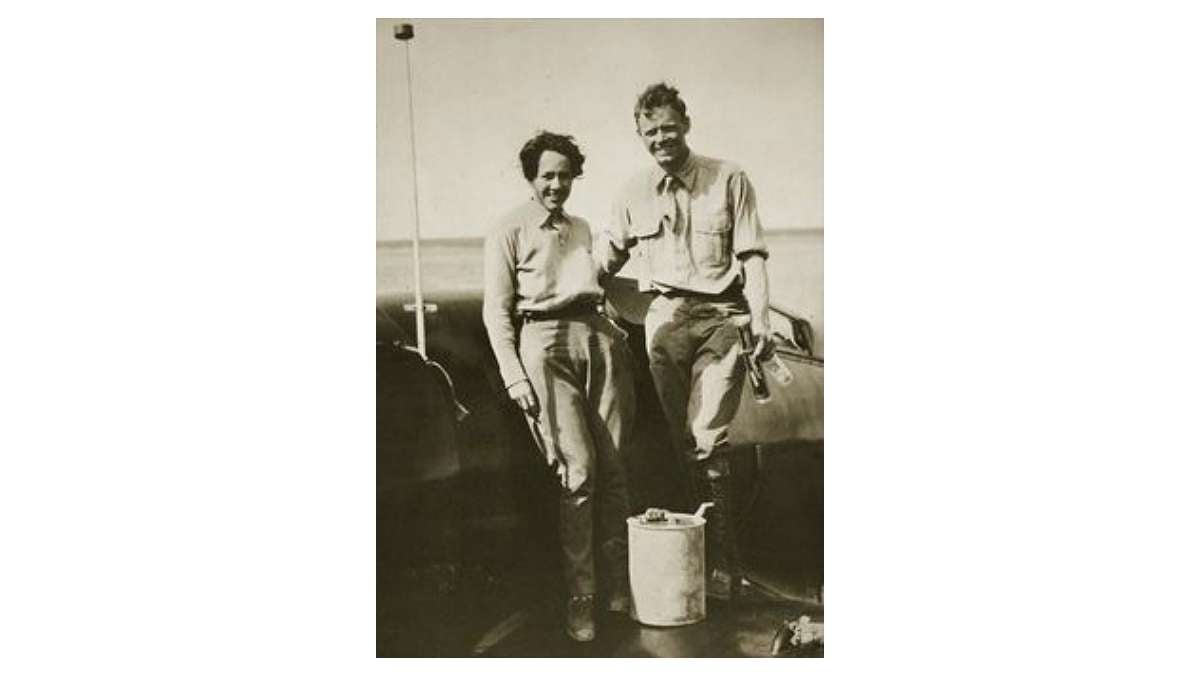

The life, and mind, of Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) and his author/aviator wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh (1906-2001), have fascinated filmmakers, biographers, novelists, TV producers, children’s book authors, musicians, postage stamp collectors and building namers for nearly a century. Woody Guthrie wrote a song about him, a dance—the Lindy—is named for “Lucky Lindy,” and of course Anne and Charles wrote their own books about their great adventures. Now comes the exhibit: Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Couple of an Age, on view at Morven Museum & Garden through Oct. 23, 2016.

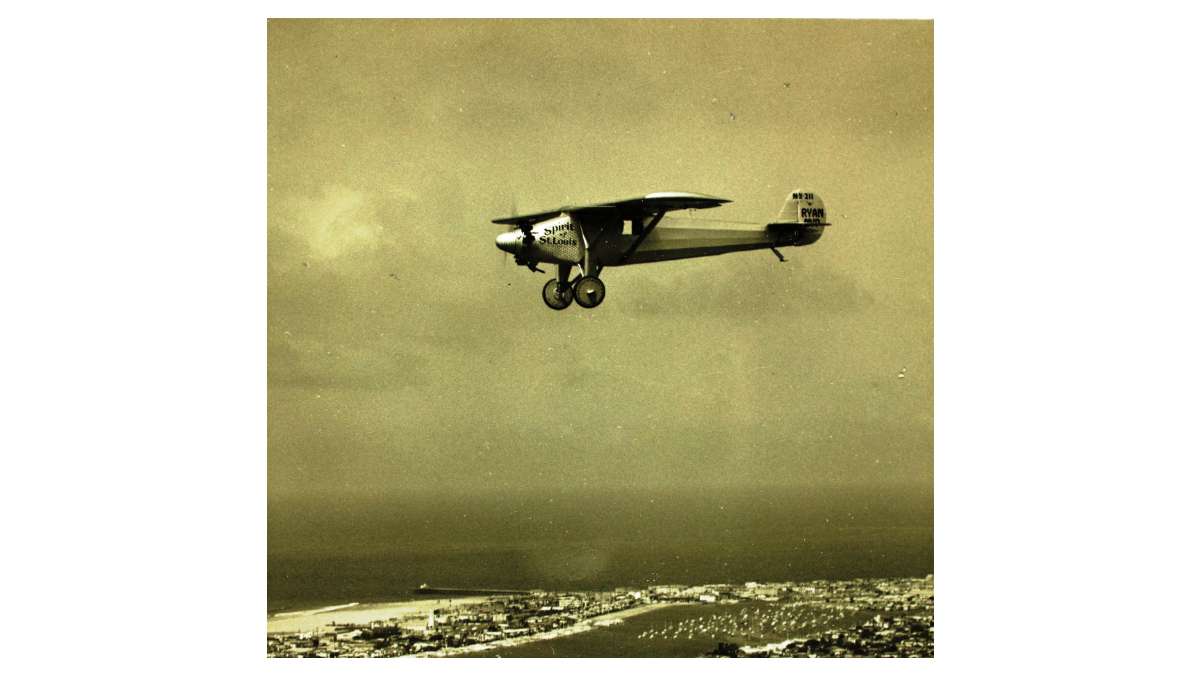

Welcoming visitors on the front lawn of Morven is a life-size replica of The Spirit of St. Louis, constructed by a crew from Baxter Construction and Morven volunteers (the original flies over the lobby of the Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.). Lindbergh’s plane was named to thank the St. Louis businessmen who provided financial backing for his transatlantic flight, making him the first person to wake up in the U.S. one day and in Europe the next.

The Lindberghs lived in Hopewell at the time of the infamous kidnapping and murder of their 20-month-old son. “The Trial of the Century,” which took place in the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington, ended in the conviction of Bronx carpenter Bruno Hauptman. He was electrocuted at Trenton State Prison, but theories continue to prevail about the kidnapping and the murderer.

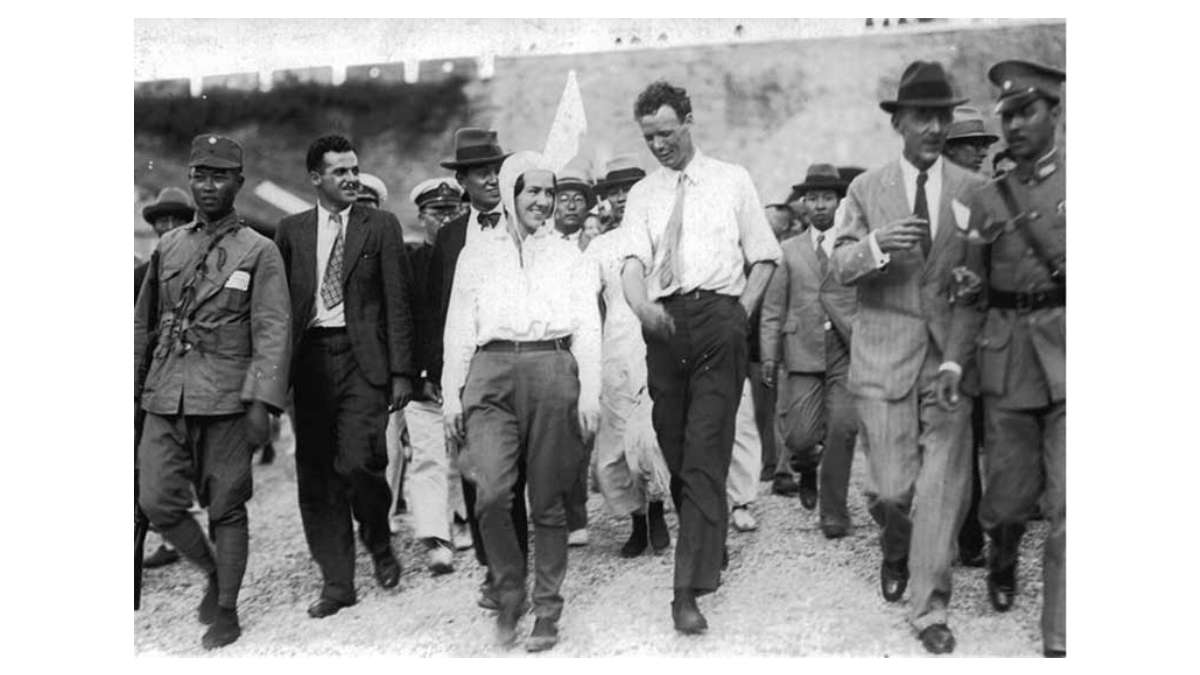

The Lindbergh story is a complicated subject. Lindbergh was a man who went from hero to victim, Nazi sympathizer and polygamist. “He went from being one of the most famous—and certainly the most photographed—Americans to one of the most reviled,” says Morven’s Director of Development Barbara Webb. Among the many objects on display is the Nazi medal given to Lindbergh by Nazi General Hermann Goering, on loan from the Missouri History Museum.

But before he fell from grace, Lindbergh was a rock star. “Modern man realized nobody had ever subjected himself to such an extreme test of human courage and capability,” wrote biographer A. Scott Berg. “Not even Columbus sailed alone.”

“I first considered the possibility of the New York-Paris flight while flying the mail one night in the fall of 1926,” Lindbergh wrote. “Several facts were outstanding. The foremost was that with modern radial air-cooled motor, high lift airfoils and lightened construction, it would not only be possible to reach Paris but, under normal conditions, to land with a large reserve of fuel and have a high factor of safety throughout the entire trip.”

While most pilots flew with a second navigator, in a second cockpit, Lindbergh preferred to use the space for extra gasoline. He needed 425 gallons weighing 2,600 pounds. To cut surplus weight he cut margins off of charts and left behind his parachute.

“In many ways Charles Lindbergh’s greatest achievement in 1927 was not flying over the Atlantic but getting a plane built with which to fly over the Atlantic,” wrote author Bill Bryson.

In the fall of 1930, after a year of living on the road or as guests, Anne and Charles began planning a private home life and bought a secluded tract of land in Hopewell. When Charles Jr. was born it became necessary to post a guard. Footage of him as a blond cherubic toddler screens on a loop.

After the kidnapping and trial, Anne and Charles moved to Kent, England, surrounded by walled gardens, and had two more children. From there they moved to a remote island off the coast of Brittany, and at the request of the American Ambassador to Germany Charles was invited to inspect the German air force.

Lindbergh cautioned “the greatest danger” posed by the Jews “lies in their large ownership and influence on our motion pictures, press, radio and government,” and made anti Semitic speeches. Denying anti Semitism, he wrote in his journal: “Whenever the Jewish percentage of the total populations becomes high, a reaction seems to invariably occur. It is too bad because a few Jews of the right type are, I believe, an asset to the country…”

FDR said to Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau in 1940, “if I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this, I am absolutely convinced Lindbergh is a Nazi.”

Lindbergh was attracted to the military efficiency of the Third Reich and may have moved to Germany but Kristallnacht made him reconsider. As the war began, Anne and Charles returned to the United States, to Darien, Conn., with their five children.

Charles also supported ideas about eugenics. In a recent book, “The Case That Never Dies,” Rutgers University historian Lloyd Gardner postulates that the Lindbergh baby had health defects and Lindbergh may have been involved in the kidnapping. Lindbergh may have wanted to quietly move his son into an institution, but the move backfired calamitously.

By the 1950s, Anne and Charles were living separate lives. Charles had relations with three German women—two of them were sisters and one was his personal assistant—and had seven additional children with them. Those children only knew their father as “Careu Kent,” and he visited them four times a year. The story came to light in 2003. Lindbergh daughter Reeve was shocked, but has since embraced her extended family. “I remember my father as a deeply intelligent and incredibly energetic man, a man of warmth and humor and charm,” she says in “Forward From Here.” “I also remember my father as the most infuriatingly impossible human being I have ever known.”

“He saw the world differently, and what compelled him to make the flight is what also compelled him to do everything he did,” says Webb. “He lived by his own rules, he thought it was OK to have four families.”

Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Couple of an Age, on view at Morven Museum & Garden through Oct. 23, 2016.

__________________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.