Praxis Dialogues: Does this place matter? Philadelphia’s preservation paradox

On February 28, PennPraxis and PlanPhilly will host the next Praxis Dialogues, the third in a series of public conversations about the notion of “the public good” in design practice. This time we’re focused on historic preservation and our panelists are sharing essays each week leading up to the event. So far we’ve heard from PennPraxis’ Executive Director Randy Mason on preservation and the public good, Penn Law professor and urban scholar (and WHYY board member) Wendell Pritchett on preservation for a changing city, and PIDC’s Prema Katari Gupta on preservation as an anchor for the Navy Yard’s redevelopment. Today we hear PennDesign professor Aaron Wunsch’s take on Philadelphia’s current preservation climate and what’s at stake.

Since the middle of the 20th century, historic preservation has attempted to re-justify itself to the American public every ten years or so. Patriotic connections to the Great and the Good (usually male and white) ceded to narrow aesthetic considerations by 1960s, only to give way, at least partially, to psychological arguments (a counterweight to dislocation) and environmental ones (the “embodied energy” of existing buildings). Around the year 2000, a loose consensus began to gather around the concept of place – thus the rise of “This Place Matters” as the slogan of the National Trust. That move felt good to some of us, at least in the academy, but it was always a bit problematic. Matters to whom? Why? And so what? And here we are again.

Self-examination is a healthy impulse, and in academia it’s what we do. Things our society holds sacred shouldn’t be immune to scrutiny (even capitalist democracy seems to have a few blemishes at the moment). What’s worrisome, at least to a practicing preservationist like me, is the tendency to veer from one credo or manifesto to the next without remembering what the last one achieved. It’s this kind of manic or Manichean amnesia that demands we choose between “tangible and intangible heritage” or, in blunter parlance, between “buildings and people.”

Sixty years ago, local architect Edwin Brumbaugh, who specialized in restoration, observed: “Old buildings acquire something from their contact with people and events, something which enables them to dramatize the facts of history, to make its actors real people, as nothing else can do.” The language sounds creaky but Brumbaugh gets it right: buildings (or the built environment) matter enormously, mostly because of their peculiar ability to communicate palpably — a process that is both subjective and objective, and thus fraught with any number of interpretive pitfalls. The latter might tempt us to retreat into a haze of “critical” doubt, but that would be silly and also lonely. Ordinary people would still want to preserve things, with or without our blessing.

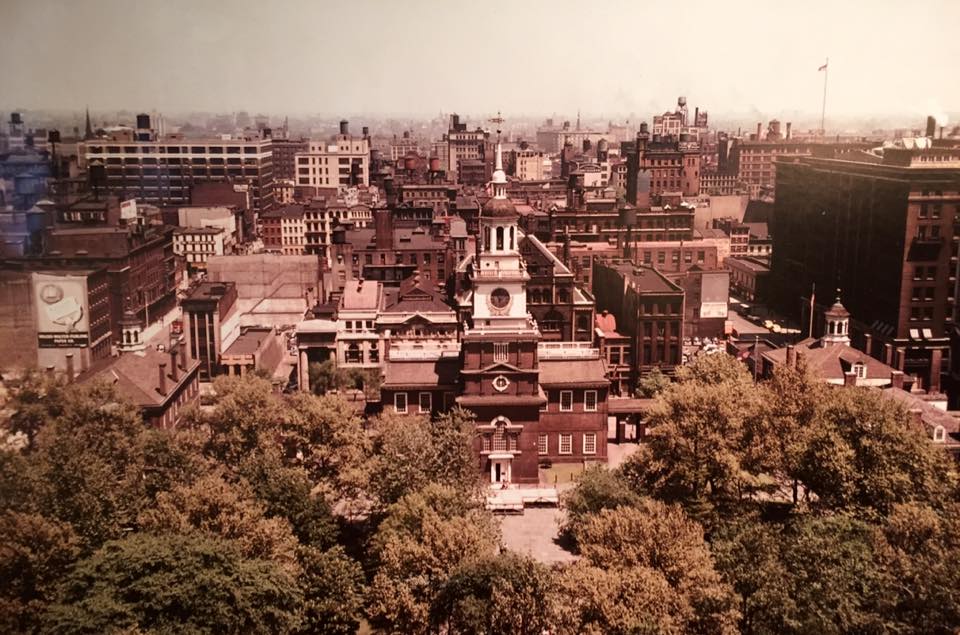

Brumbaugh was thinking of the then-intact area around Independence Hall—the same totemic zone mentioned by Wendell Pritchett in his recent Praxis Dialogues essay. That district was our equivalent of New York’s Penn Station – lost, lamented, a call to action. Its fate still has much to teach us, as does the present-day demolition of the Sharswood neighborhood and promises of the same for Jewelers Row. How much have we actually learned? Whatever lip-service we accord Jane Jacobs – or even Ed Bacon – our default impulses as a city still hew closer to Robert Moses (whom most readers have heard of) and Boies Penrose (whom most readers haven’t).

Why do we get stuck in this rut? How to explain the odd paradox that Philadelphia, despite its storied obsession with “heritage” (now deployed as global marketing tool), still treats preservation as a joke by virtually any substantive measure (funding, staffing levels, policies)? Surely there’s no single answer to that question. Still, it’s hard to ignore what might be termed the Fear-of-Detroit Syndrome in which we’re encouraged to believe that even the slightest curtailment of developer perks and prerogatives will lead directly to our economic downfall. Among other things, this means we really can’t have candid discussions about the impact of current zoning, housing, and tax policy on preservation because those policies are considered sacred, indeed almost natural rather than man-made. Instead of talking about how these tools could be adjusted to work in preservation’s favor, we’re reflexively reminded how much good they’ve done. It’s hard to have a productive conversation when the opener is: “Don’t you know how much better things are now?” It reminds me of the old saw about shutting down your opponent with the opener: “So, Mr. So-and-So, when did you stop beating your wife?”

Interestingly, though, local officials will almost always declare themselves in favor of preservation – at least until the moment they have skin in the game. To hear them tell it, it’s not that preservation is unimportant, it’s just so much less important than everything else at a given moment. Maybe we can afford to think about preservation when the city’s economy is strong. Now the city’s economy is strong? Why would anyone want to kill that with preservation? Other variants include: Sure, preservation is nice, but its value pales in comparison to such and such social good (which happens to be embodied in its purest form by whatever is currently being proposed and couldn’t possibly be achieved elsewhere, including on the adjacent vacant lot). After years of accepting this argument in different venues, we end up where we are today, with an impoverished and enfeebled preservation system whose own operators can’t or won’t articulate why preservation is a public good.

Allow me to restate another wife-beater question: Why do you care more about buildings than people? My answer is that I care about both, sometimes for similar reasons, and that the dichotomy between the two is often exaggerated, even demagogued. Sometimes it is entirely fictional. Are there cases in which private or social needs genuinely require the complete obliteration of a particular building or landscape? Of course there are. But as long as removal remains the default rather than a last resort, we will continue to fill landfills with good materials, waste untold amounts of fossil fuel, destroy social capital, and impoverish our sense of place and with it our sense of ourselves. We will lose our city’s soul and maybe bits of our own. We may even impoverish city coffers in the long run by replacing sturdy, character-rich fabric with the flimsy, generic boxes that mushroom under the 10-year tax abatement and current zoning. There’s a reason people are flocking to old cities, especially to their oldest parts, and it isn’t because they can find exactly the same thing in these places as they can find in any other part of the country. Unfortunately, the sobering reality is that preservation has been an afterthought in Philadelphia for a generation and now it’s very hard to play catch-up. Boom-town zoning and tax breaks have left property owners and developers with the conviction that they are being robbed if these government-supplied perks are taken away.

When we gather on February 28th to discuss these issues, I hope we can address them forthrightly. And, following Randy Mason’s lead, I hope we can situate them in a broader intellectual framework. Toward that end, I’d like to offer three specific themes (with examples to follow) that might lend focus to some of our discussion. These are: Tokenism, Connoisseurship, and Gentrification. I’d also like to offer hope. As Rebecca Solnit reminds us, those of us who are unhappy with the status quo have an obligation to be courageous and persistent. Preservation is strongest when its grass roots are thriving. “If you don’t like the news…go out and make some of your own.” See you, I hope, at the Philadelphia History Museum.

Praxis Dialogues: Preservation and the Public Good will be held at the Philadelphia History Museum on February 28 at 6:30pm. Register here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.