Photographers reinterpret the landscape at Rider University

When we think of the landscape, the first thing that pops to mind may be a J.M.W. Turner painting, a romantic vista of the world 300 years ago, with dramatic skies and weather, possibly light breaking through a cloud, brilliantly illuminated trees, water frothing and foaming between rocks.

There are many painters and photographers today who seek to create, in the name of landscape, a pastoral beauty, and yet our world is not like that anymore.

The landscape, seen through the windows of the vehicles that dominate, often is made of crumbling factory buildings, railroad cars, cell phone towers and high tension wires, modular housing and gas stations.

Landscape: Social, Political, Traditional, on view at Rider University Art Gallery through Oct. 12, shows a provocative landscape. “In putting forth the idea of landscape photography, one need only look at its history to see a vision of portraying beauty as an answer to painting,” said Curator Aubrey J. Kauffman. “Creative possibilities arise in interpreting the artist’s relationship to the environment that is seen through the lens but initially through an idea.”

The choice of subject, viewpoint, lens, framing and timing determines what the image will convey, Kauffman said.

“In exploring the relationship between people and place, social landscape photography is informed by aspects of our everyday interactions,” he said. The four artists exhibited here “diverge in their interpretations and vision of a social and political aspect that serves as an overlay to their art.”

Wendel A. White, Distinguished Professor of Art at Richard Stockton College, explores “Schools for the Colored” in his series of black-and-white photo montages. “It is a continuation of my journey through the African American landscape,” said the Newark native. “In ‘Schools for the Colored’ I pay attention to the many structures and sites that operated as segregated schools.”

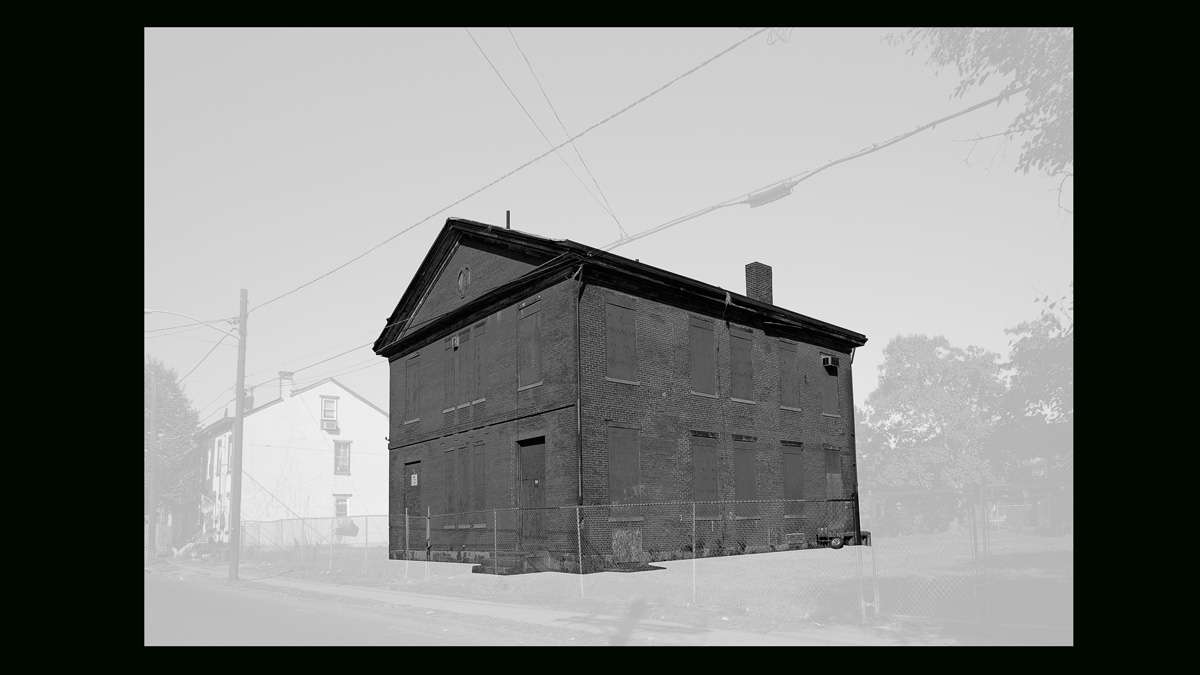

We see Indiana Avenue School in Atlantic City, the New Jersey Manual and Industrial Training School for Colored Youth in Bordentown, Manitou Park School in Berkeley, and Bellevue School for the Colored in Trenton, printed in a deep black and white pigment. They are surrounded by a veil – a digital imaging technique that obscures the surrounding landscape. White connects this veil to a description of an early school experience in W.E.B. Dubois’s “The Soul of Black Folk”: “I was different from the others; … in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world by a vast veil.”

The schools, of course, no longer exist, and in some cases the building is no longer there, so the artist uses silhouettes as placeholders.

“This area, sometimes referred to as ‘Up-South,’ encompasses the northern ‘free’ states that bordered the slave states,” writes White, who has received numerous awards including a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. “The architecture and geography of America’s education Apartheid, in the form of a system of ‘colored schools,’ within the landscape of southern New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, is the central concern of this project.”

Another school looks like a boarded up shack with peeling paint. The “veil” sets it against a snowy woods, looking quaint and New England-y – the ugly reality is made beautiful with digital magic. In Trenton, the brick structure – once a stately building – has its windows boarded up and is surrounded by a chain link fence.

Annie Hogan – an Australian photo media artist who studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago – is interested in former plantations in rural settings that are now tourist attractions. “I explore how these structures speak to the interdependency and uneven symbiotic historic relationship between the former enslaved and enslaver,” she said.

She uses a technique similar to White’s veils, creating a reflection of the outside over a stark white interior of a room or an architectural structure. The architecture and the built world folds into the world of trees and skies.

In order to set themselves apart from the hordes who document the details of daily life with cell phones, exhibiting artists tend to print their images as large as modern art canvases, but Hogan is able to make her large statements in small format. In one we see a woman from Colonial times, hair in a bun, outside a small wooden hut; in another, an antebellum mansion is reflected. We’re definitely in the Civil War-era South, and the overlay of painted colors on “Over a Blood Soiled Land” obscures the ugly reality. “I explore the spectacle of re-enactments as public performance… and reflect on the relationship of the Civil War to the end of slavery,” she said.

“Since its inception, the camera has been used as a tool to document tragedy,” said New Jersey native Josh Brilliant, who lives in Philadelphia. “Often considered a method for validation, the photograph serves as a replacement for memory whether positive or negative.”

His “I am the Night” series questions how a photograph can be made about tragedy without showing tragedy. The large gray-scale inkjet prints – which impart a negative quality – show lifeless trees, vines, branches and bales of hay. “Can a tree regrow after serving as an accessory to murder?” he asks. “This series… is about questioning the memory of a landscape.”

From these three artists, we see little color and no people. Joshua Lutz finds the color and the people in the Meadowlands, nevertheless evoking its loneliness and emptiness. We see a plane taking off next to a cell phone tower; the draped netting filtering the sky over Meadowlands Golf and Marina and Waterfront Café; a man in a turban with a long white beard, squatting in a chili pepper field adjacent to a Citgo station, where a semi has stopped for refueling.

At dusk, through the leaves of trees, we see the parking lot of the Delayed Cares Motel (air conditioned, promises the neon sign), with yellow concrete bumpers at the end of the lined parking spots.

A priest in black garb with white band at the neck stands in a field of dried goldenrod and aster. His hands splay out from his side. He’s waiting. Has he seen something too frightful to confront? The landscape can be a frightening place.

Landscape: Social, Political, Traditional is on view at the Rider University Art Gallery through Oct. 12. Discussion of the artists’ work Oct. 2 at 7 p.m. Admission is free.

___________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.