Philly’s Mutter Museum sharpens focus on the Civil War’s slain and wounded

“Future years will never know the seething hell and the black infernal background of countless minor scenes and interiors,” wrote the poet Walt Whitman about the Civil War. “It is best they should not — the real war will never get in the books.”

Whitman saw the war not from the vantage point of Little Round Top, or Seminary Ridge, but as a nurse tending to the soldiers whose lives and bodies were ripped apart by the conflict. Some of those bodies — what remains of them — are on display at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia.

“This exhibit is really the history of the body,” said museum director Robert Hicks. “The battle comes. The battle leaves. Somebody wins. Somebody loses. The medical dimension of the war is still happening.”

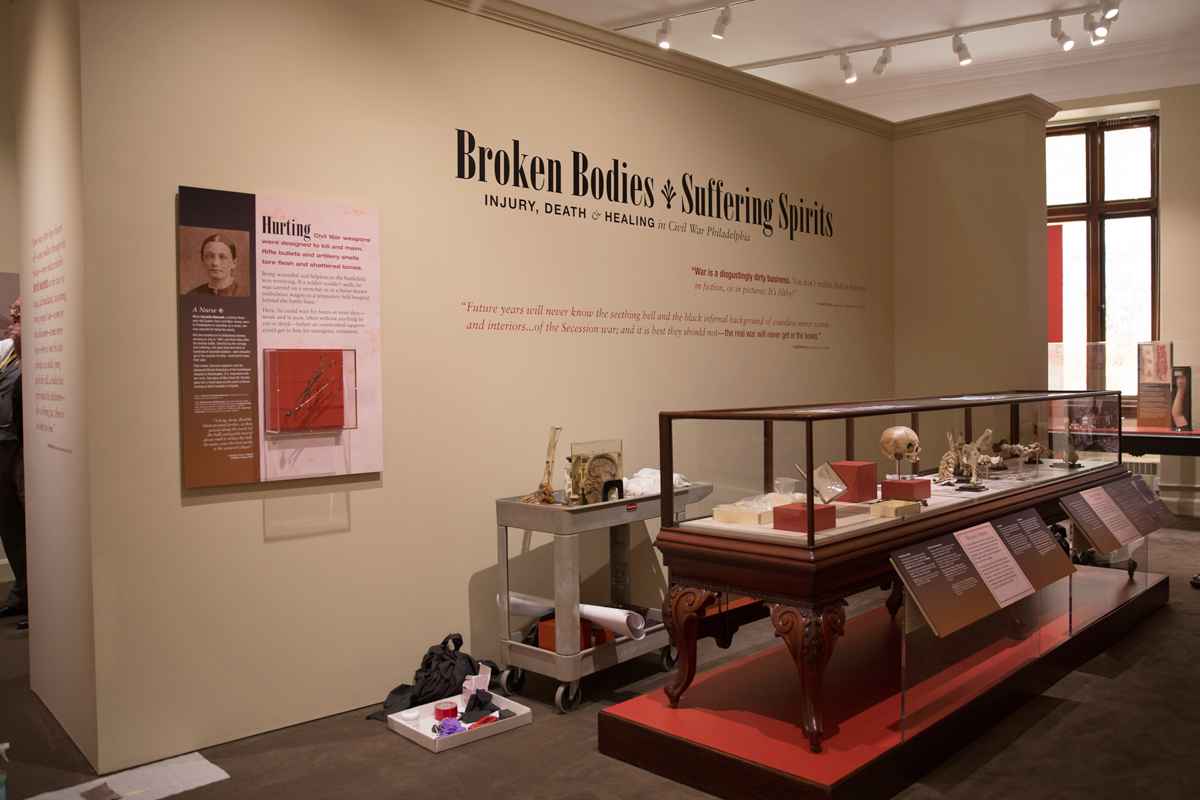

The museum, part of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, is famous for its gruesome medical abnormalities and pathologies in jars. Its new permanent exhibition, “Broken Bodies, Suffering Spirits: Injury, Death, and Healing in the Civil War,” is on par with the rest of the collection.

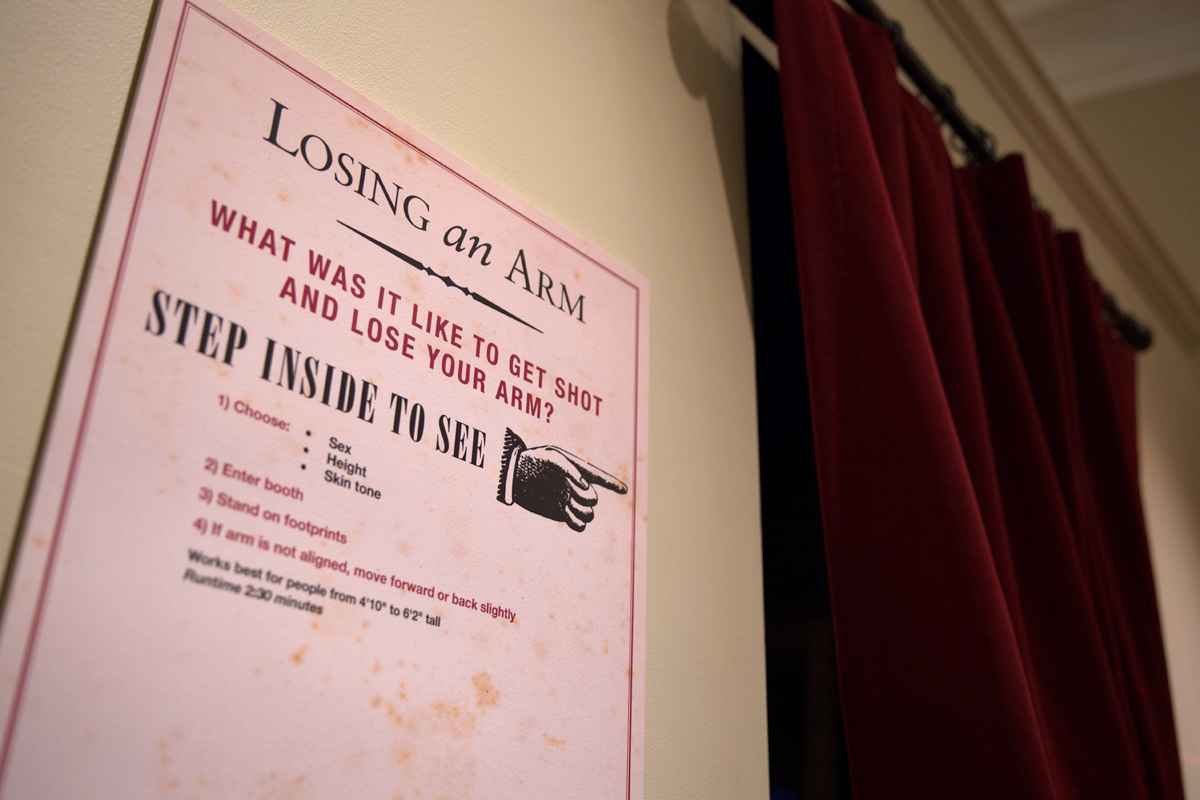

Upon entering a newly renovated room of the Mutter Museum at the College of Physicians, the first thing you see is a case of human bones that have been damaged by rifle-musket bullets. They all had been amputated from bodies of soldiers 150 years ago. Some of the bones are still embedded with the lead bullets fired by the enemy — called Minie balls, named after the Frenchman who invented the grooved, pointed shape that gave them deadly accuracy.

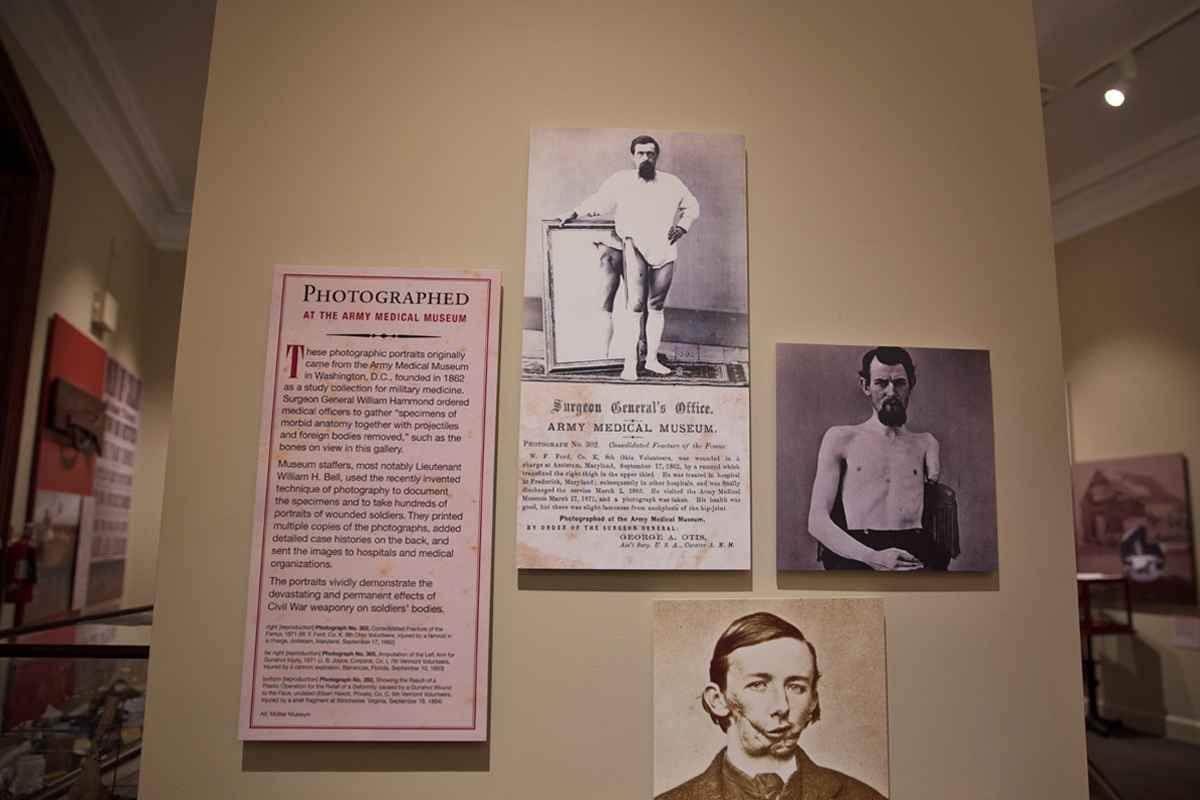

“Most physicians before the war had never seen gunshot wounds,” said Hicks. “So the Army created the Army Medical Museum during the war, in Washington. There was a standing order for physicans in the field — when they see something of pathological interest, they had to package it up and send it to Washington. And I mean severed limbs.”

Widespread death gave birth to medical advances

The idea of systematic hospital treatment for large numbers of patients did not exist before the Civil War. Huge hospitals were quickly erected in West Philadelphia and Chestnut Hill to care for the tens of thousand of soldiers evacuated from battlefields. Photos on display in the exhibition show hospitals so large, that they were outfitted with their own internal trolley systems.

Ideas as basic as the ambulance, and as nuanced as phantom limb syndrome — wherein patients feel physical sensations where a limb no longer exists — developed during the Civil War.

The most gruesome irony is that the wounds suffered by Civil War soldiers from crude Minie balls — which would flatten and shatter upon impact — are being seen again, now, as a result of terrorist explosives of homemade shrapnel.

“The improvised weapons — the roadside bombs that have disabled so many of our soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan — have a direct connection to the Civil War,” said Hicks. “After the Civil War, weapons changed, they got more sophisticated. But back to these improvised weapons that we now experience, they resemble in their consequences what Minie ball and musket balls did during the war.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.