Philly to start tracking doctors to target opioid overprescribers

Roughly 1% of the doctors write a quarter of all opioid prescriptions, and another 10% write half of them. Half of the doctors don’t ever prescribe opioids.

(Toby Talbot/AP Photo)

Despite their yearslong effort to urge doctors to prescribe fewer opioids, Philadelphia health officials say there are still too many pills being dispensed in the region. They know from state data, provided by the Pennsylvania prescription drug monitoring database, that a very small number of physicians in the area are responsible for most of the overprescribing. But because the state data does not include identifying information, local officials have no way of knowing who to go after.

Thanks to new legislation passed during Philadelphia’s last 2019 City Council session, that’s about to change.

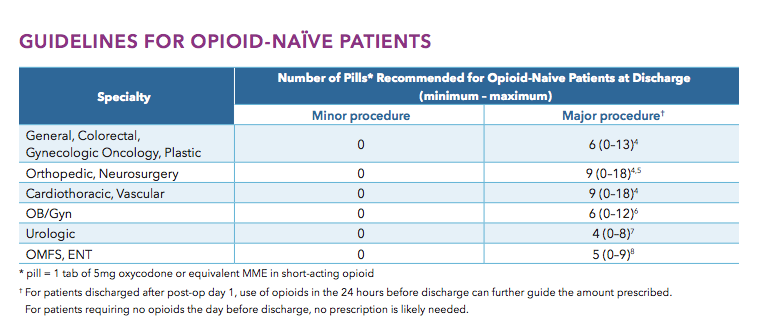

In 2018, health officials issued new prescribing guidance to more than 15,000 doctors in the Philadelphia region. Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said his department sent staff into more than 1,000 offices to work directly with doctors to curb prescriptions and come up with alternative approaches to pain management. By most accounts, it’s working: According to city data, the number of opioid prescriptions decreased by 30% between early 2017 and early 2019.

Even so, Farley said, there are still too many prescription drugs floating around.

“We find that, despite the large amounts of publicity, there are still some doctors out there that don’t understand that their prescribing practices really aren’t good for their patients in the long run,” he said. “They were taught for years to prescribe more opioids.”

Farley said he can tell from the regular reports he gets from the state’s prescription drug monitoring program that most of the city’s opioids are coming from just a few doctors. Roughly 1% of the doctors write a quarter of all opioid prescriptions, and another 10% write half of them. Half of the doctors don’t ever prescribe opioids.

The only problem is, the city knows this from a consolidated report issued by the state that doesn’t include the physicians’ names.

“We can use that for statistics, but we can’t use that for educating individual physicians,” said Farley.

The new law will require pharmacies to send regular dispatches to the city Health Department for all controlled-substance prescriptions. The report will include the name of the prescribing doctor, the type of drug, how much is being prescribed, and how often. Pharmacies will also have to create a unique identification number for each patient, protecting that patient’s anonymity but still tracking patterns.

If health officials notice a pattern of overprescribing, a physician will be flagged and receive education from the Health Department. The city will then be able to track whether the doctor’s prescriptions went down over the next reporting period. If they don’t, Farley said, the Health Department will work with law enforcement to come up with appropriate consequences.

Prescription data-monitoring databases have been criticized for their potential to serve as a direct line between vulnerable patients and law enforcement. While the Philadelphia version won’t identify individual patients, critics have also expressed concern that if doctors know they are being closely monitored, they might be hesitant to prescribe a controlled substance even if it is the best option for the patient. If patients who have become dependent on opioids are tapered off too quickly, research has shown they may turn to less-regulated, illicit opioids such as heroin and fentanyl where the risk of overdose is higher.

Farley stressed that because the effort is specifically to target that subsection of high prescribers, he did not anticipate this being an issue.

Eva Gladstein, the city’s deputy managing director of health and human services, said they wouldn’t have gone the legislative route if they didn’t have to. But the state regulations are narrowly written, she said, and while state officials can see prescribers by name, they interpreted the law as not permitting them to share that information with municipal departments.

“I would say we spent two years working with the state to see if we could get the data so we didn’t need to do this,” Gladstein said.

Farley said the new program was still a few months away from rolling out because they still have to come up with the exact reporting regulations. He said one pharmacy chain was dragging its feet about adopting the new law, but declined to say which.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.