Philly activists who burglarized Hoover’s FBI call for more whistleblowers

If all went according to plan, Raines and fellow anti-war activists would pull off a burglary that would go down in history as exposing J. Edgar Hoover’s secret surveillance of groups demonstrating the war in Vietnam.

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV.

It was Bonnie Raines’ job to case the joint.

Her target: the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania. If all went according to plan, Raines and fellow anti-war activists would pull off a burglary that would go down in history as exposing J. Edgar Hoover’s secret surveillance of groups demonstrating the war in Vietnam.

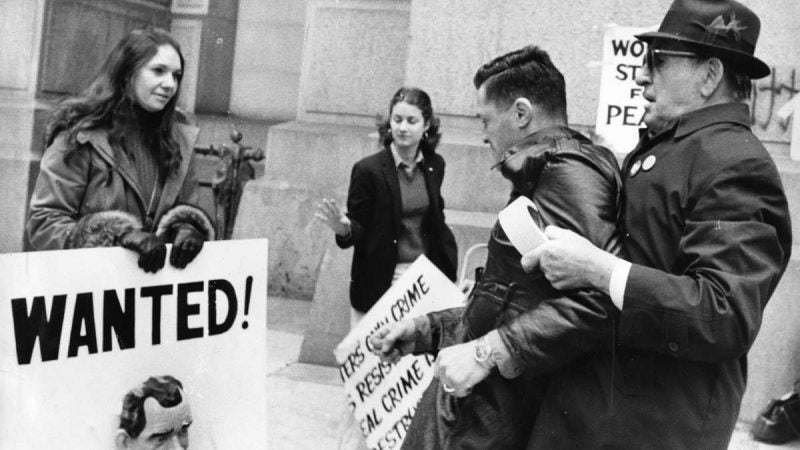

Raines tucked her long brown hair under a knit cap, donned a pair of fake glasses and posed as a nearby Swarthmore College student doing research on the FBI.

She was pretty and the male agents were accommodating. She made a mental checklist: where the doors were, how many had locks, how many windows the office had.

“I don’t think I was scared,” Raines said. “I think a little bit of the actress came out in me. I realized that I had a significant small role to play that was going to lead to our success and I was into that role … I was very flirty.”

And so, on March 8, 1971, when most Americans were glued to their radios listening to Philadelphia’s hometown hero Joe Frazier take on Muhammad Ali for the world heavyweight boxing crown, Bonnie Raines, her husband John, and six other ordinary Philadelphians pulled off an extraordinary burglary that would change the way the FBI conducted future investigations.

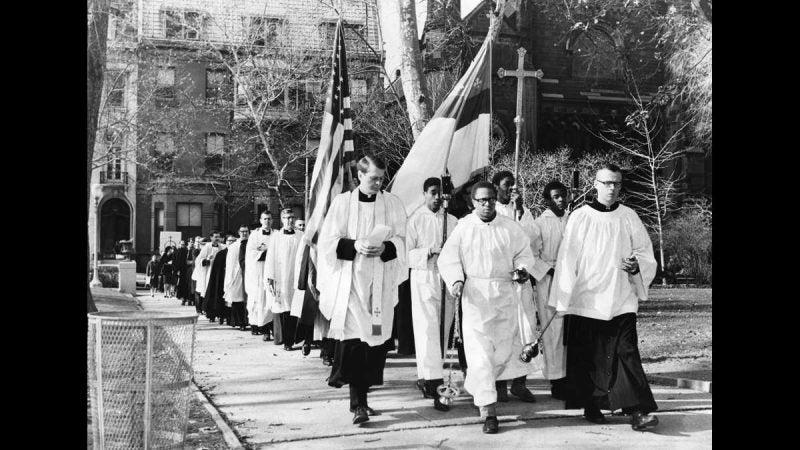

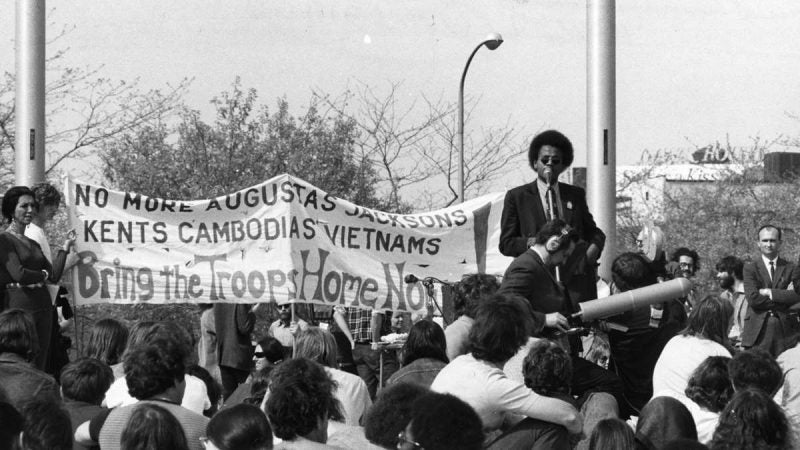

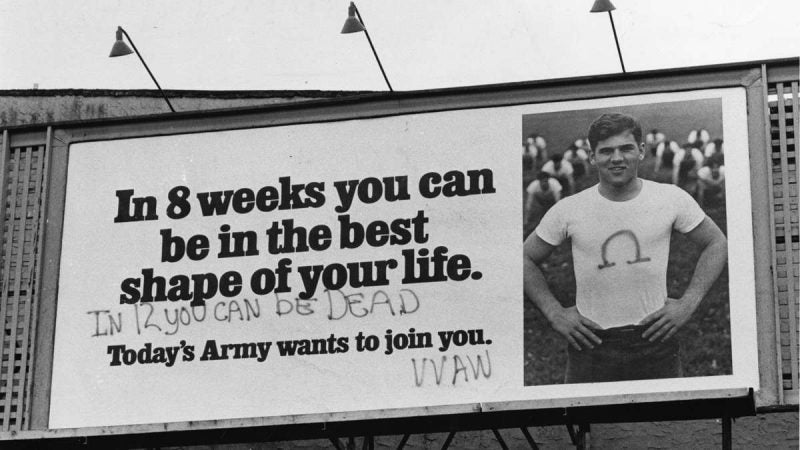

While 40,000 young men were drafted into the military every month during the height of the Vietnam War, John and Bonnie Raines had become increasingly frustrated. They had demonstrated against the war for more than two years with little result. Then, in 1969, President Richard Nixon called for secret bombings in Cambodia, escalating the war, not ending it.

“Our country had gone off the track morally,” said John Raines, a retired professor of religion at Temple. “The country got involved in a war that we never should have gotten involved in. The people in Washington who had the responsibility to guide the nation weren’t doing their jobs. So when things in Washington go haywire, we the people have to engage in resistance.”

Led by late Haverford professor and peace activist Bill Davidon, the John and Bonnie Raines joined a group of eight who planned an act of civil disobedience that would be considered radical by today’s standards. Their intention was to steal key FBI files, send them to the press and blow the whistle on Hoover’s secret agency. The group called itself the “Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI.”

John Raines wanted to expose Hoover. Raines had been arrested and jailed during the Freedom Rides in Little Rock, Arkansas a decade earlier. He’d heard how Hoover wiretapped Martin Luther King Jr.’s phones and used illegal surveillance to monitor the civil right leader. He said he knew the FBI director was employing the same tactics against peace activists.

The trick was to prove it.

“We knew Hoover had informants and was tapping phones and was attempting to suppress dissent,” Bonnie Raines said. “So that was the challenge, to get the documents and the evidence to the public.”

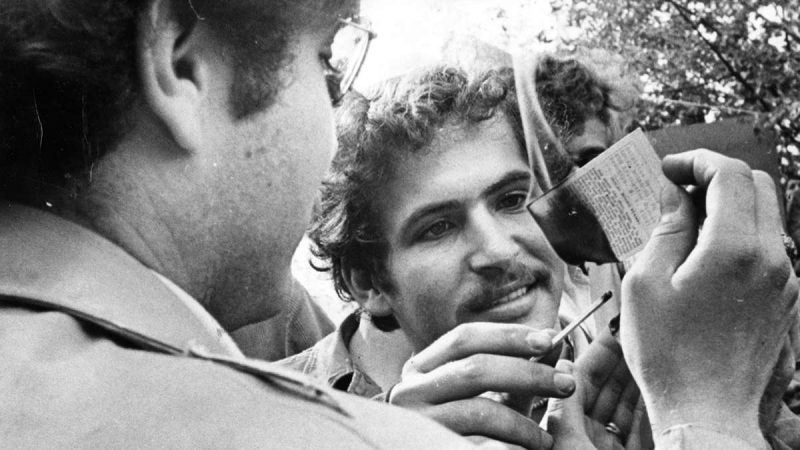

Davidon tapped Keith Forsyth, days shy of his 21st birthday, to conduct the break-in. Forsyth had hitchhiked to Philadelphia from Ohio months before to become more involved in the peace movement, and built a reputation as a solid lock-picker.

Forsyth dressed for the part in a thrift shop Brooks Brothers jacket, a tie and a law enforcement haircut. Everything went according to plan, except for one thing: an unexpected lock on the front office door.

“I went from nervous to freaking out,” Forsyth said. “It wasn’t just any old lock. It was a high security design that is much harder to pick then a regular lock. I was like, ‘Arrgh! What am I going to do now?’ ”

From Bonnie’s casing, Forsyth knew there was a side entrance. He picked the lock and broke the deadbolt, only to discover a file cabinet blocking the entry into the office. He went back to his car and got a jack out of the trunk he used to pry the file cabinet away.

“It probably didn’t take that long, but it seemed like a really, really, long time to me,” said Forsyth, now 66, his lanky frame sprawled on the couch in the Manayunk home he shares with his wife.

“If somebody came along, I could hear them wondering, ‘Why are you laying in the hall outside the FBI office with a jack in your hand?’ ”

John Raines drove the getaway station wagon to a Quaker farmhouse in Bucks County. Wearing gloves, the eight went through suitcases full of files and sent the most egregious ones to the press — including documents that exposed COINTELPRO, Hoover’s secret counter-intelligence operation aimed at disrupting dissent movements nationwide.

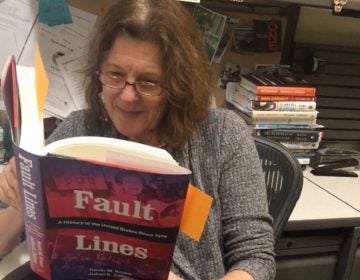

Betty Medsger, then a reporter at the Washington Post, wrote a front-page story. A furious Hoover dispatched an army of 200 agents to track down the culprits.

Yet, they all managed to get away with it, while hiding in plain sight in their Germantown neighborhood.

“The peace movement wasn’t just eight people in a room someplace,” Forsyth explained. “It was thousands and thousands and thousands of people in Philadelphia. So there were an awful lot of suspects.”

It was at a dinner party 43 years later, decades after the expiration of the crime’s statute of limitations and Hoover’s death, that John Raines let slip to Medsger that they were indeed the burglars. By then the five-year statute of limitations for their crime had long since passed. Hoover was long gone too, dying of a heart attack in 1972.

Their action led to Medsger’s book “The Burglary” and a Netflix documentary, “1971.” But more importantly, it forever changed the way the FBI would operate as a law enforcement agency.

An FBI spokesman told the New York Times in 2014 the action prompted changes in the agency’s “intelligence policies and practices and the creation of investigative guidelines by the Department of Justice.”

John, now 83, and Bonnie, 75, say they understood the enormous risk they took as young parents with three children under the age of 10 at the time. They had arranged with family members to care for their kids if they were sent to prison. But they say they would do it all again to preserve a democracy they consider precious — especially now under President Donald Trump, an administration they see as repressive.

“There’s many opportunities for people to be whistleblowers like we were,” Bonnie said. “There’s so much going on that is nefarious and illegal and undermining our Constitution. It’s a dangerous time and people are beginning to realize that the reversal of policies calls for some real activism.”

John Raines has always seen dissent as having a rightful place in history. But with the benefit of hindsight, he sees it even more clearly.

“Looking back on it from 50 years later,” he said, “we discovered that being on the streets finally won the future.”

To learn more, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War” running Sunday, Sept. 17 at 8 p.m. through Thursday, Sept. 28 on WHYY-TV. WHYY Members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.