Philadelphia working with Penn microbiologists to check for coronavirus variant

Whole genome sequencing checks for coronavirus variants. The city and the university are working out the details of a partnership going forward.

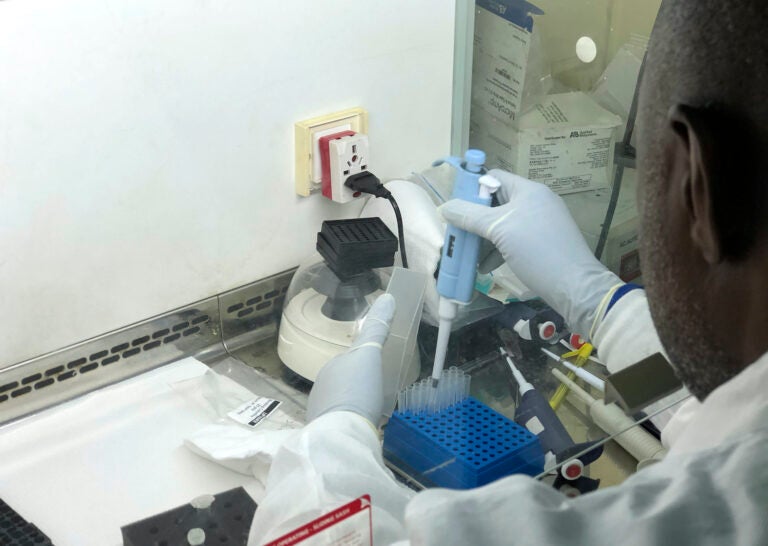

In this photo taken on Friday Dec. 25, 2020, Virologist Sunday Omilabu in a lab, during an interview with The Associated Press in Lagos, Nigeria. A Nigerian scientist spent the holiday season in his laboratory doing genetic sequencing to learn more about the country’s COVID-19 variant. (AP Photo/Lekan Oyekanmi)

Ask us about COVID-19: What questions do you have about the current surge?

Pennsylvania confirmed its first case of COVID-19 from the B.1.1.7 variant of the virus on Jan. 7.

That’s a version that emerged in the U.K. and seems to spread more quickly, according to preliminary data. The person infected with the variant was exposed while traveling outside the United States.

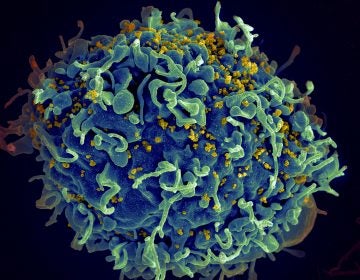

One of the ways to check whether someone has been infected with the B.1.1.7. variant, or other variants, is called viral whole genome sequencing. That means looking at all the genetic material of a virus to see how it compares to another one. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that right now there is no evidence that the variants lead to more severe illness or a high risk of death from COVID-19.

But it’s hard to tell if there are more of these cases in this country because the U.S. is not doing enough of the sequencing to check for the variant. A July report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine said current sources of coronavirus genome sequence data in the U.S. and efforts to integrate that with clinical and epidemiological data are “patchy, typically passive, reactive, uncoordinated, and underfunded.” The Washington Post looked at several databases along with their reporting and in December ranked the U.S. 43rd in the world when it comes to the percentage of coronavirus cases that were sequenced.

Scientists in Philadelphia have started doing lab work to see whether people are getting infected by this variant. Microbiologists at the University of Pennsylvania have already started sequencing samples from patients at Penn Medicine hospitals.

The city has also sent a sample to the university for sequencing, and they are working out the details of a partnership going forward, according to James Garrow, director of communications for Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health. He added that the city is working with the Association of Public Health Laboratories and the CDC on either doing more sequencing in the city, or sending samples to the CDC.

The CDC has been sequencing samples from state health departments and public health agencies since November, and the system is being scaled to process 750 samples nationally per week, according to a Jan. 3 update from the agency.

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is the other organization that can do this kind of sequencing, city Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said at a press conference on Jan. 5. A hospital spokesperson said all they can say right now is that they are “ramping up efforts to test for the new strain.”

Frederic Bushman, a professor of microbiology at Penn, said his lab group can process more samples.

“It’s fairly straightforward with a lot of software written to analyze each new batch and output … digestible visual summaries and stuff like that,” he said.

Collecting, labeling, and sending the samples is what takes time, and limits them from doing more quickly.

It’s normal for viruses to mutate. When a virus makes copies of itself, it has to copy all its genetic material, and mutations come out of copying errors.

Bushman said sequencing samples of the viruses that infected people also helps us learn more about how a disease spreads. For instance, his group will soon publish a paper showing that they learned the virus most likely came to Philadelphia from New York because the strains here most resemble the common ones in New York. Back in April of last year, researchers who sequenced coronavirus samples from New York cases in March showed the virus spread there from Europe, not from Asia.

He added that as of now there is no reason to think that the current vaccines will not work against the new variants of the coronavirus, but it is something to keep studying.

If needed, vaccines can adjust to address variants of the same virus, such as how the flu vaccine changes every year. But Bushman explained that unlike flu viruses, scientists do not expect the coronavirus to mutate as often.

First of all, the part of the coronavirus that makes new copies of genetic material has some built-in proofreading function that leads to fewer errors or mutations. Also, the genetic material for the flu virus comes in eight pieces, and someone infected with two different strains of the virus can have copies that combine parts of both strains, leading to more possible changes. The coronavirus genetic material comes in one piece, Bushman said.

“That’s a good thing,” he said. “It may mean that vaccines are much easier to make and deploy and that antiviral agents work, and there isn’t the same rate of development of resistance.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)