Philly Ethics Board 1, dark money 0

Philadelphia Board of Ethics regulations require that the group behind this ad -- an attack on mayoral candidate Jim Kenney (left) and union leader John Dougherty -- disclose who paid for it next month. The city regulation holds even groups formed as nonprofits to a strict standard of transparency.

Behold, a principle is established: There will be no anonymous stink bombs in Philadelphia elections.

In a development I find remarkable, the city Board of Ethics seems to have set a standard of disclosure in political advertising that is tougher and more effective than anything happening in federal campaigns.

And, come June 18, we should know the names of the donors who funded a late-inning attack ad in the mayor’s race, despite efforts to keep them secret.

“It’s unusual, it’s bold, and I think it’s really a strong move for the people of Philadelphia,” said John Dunbar of the Center for Public Integrity in Washington, a national expert on campaign finance issues.

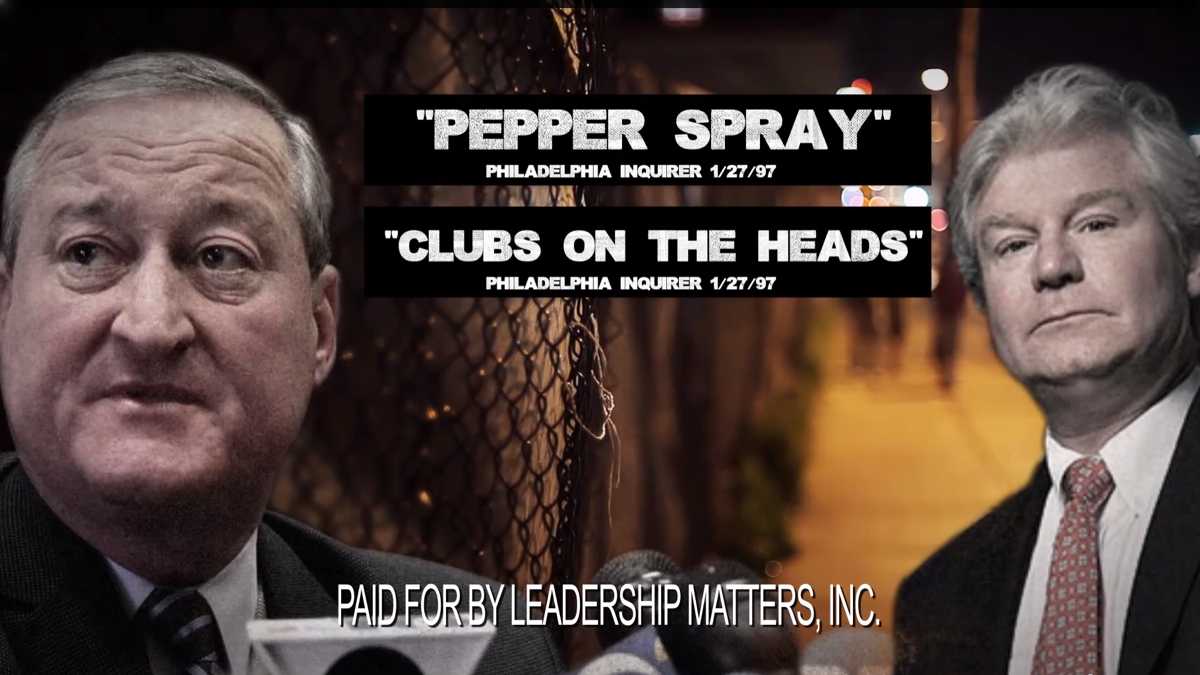

To recap: In the waning days of the Democratic mayoral primary, a hard-hitting TV ad appeared attacking former City Councilman Jim Kenney, the eventual winner.

The group behind the ad, called Leadership Matters, had recently formed as a nonprofit corporation, a move national groups use to keep their donors secret. You’ve no doubt read about this. They register as charitable organizations, then act like political committees but refuse to file the campaign finance reports required of candidates and committees, including independent expenditure committees, so-called super PACs.

And because the Federal Election Commission is paralyzed by partisan deadlock and can’t make anybody do anything, these nonprofits get away with it. Millions and millions are contributed in secret.

“It’s an affront to anyone who cares about transparency in government,” Dunbar said.

Philly draws a line

The Philadelphia Board of Ethics decided that anyone or any group spending serious money to affect a Philadelphia election has to file campaign reports the same as anybody, even if you call yourself a nonprofit corporation.

So when Leadership Matters emerged with its ad, the question was hanging: Would it comply with the board’s requirement and file a report of its late-campaign expenditure? It didn’t at first, but after I called the group’s executive director and noted that the group appeared to be in violation of the city’s campaign finance laws, he called the group’s lawyer and they filed the report, albeit a few days late.

That report didn’t reveal the group’s donors, just the size of its spending on the ad’s production and placement — $93,000.

But the fact that the group complied with the expenditure report requirement means that, unless they reverse field and say they’re somehow exempt, they’ll file a post-election report disclosing their donors, along with the donors’ addresses, occupations and employers.

You might say it stinks that they don’t have to reveal those names until after the campaign is over, and you’d be right. But the reporting schedule is the same one candidates and other committees are governed by, and by the next election it’s likely City Council will impose more frequent reporting requirements.

Revolt against dark moneyDunbar tells me that while the Federal Election Commission continues to let nonprofits keep their donors in the shadows, a number of states and cities like Philadelphia are insisting that they come into the light.

“It is absolutely within the rights of state and local jurisdictions to pass disclosure laws that are more restrictive, and we’re seeing that happen more and more,” Dunbar said. “I think what they’re doing in Philadelphia is a tremendous step in the right direction.”

So go figure: Philadelphia, the land of machine politics, so often called corrupt and contented, turns out to be a leader in a key index of political ethics.

It’s kind of revolting to think that, by next year, we’ll see a presidential campaign awash in dark money, while state and local governments at least make big donors reveal themselves.

But it’s a start, and I like the idea that the Cradle of Liberty could become the cradle of political transparency, even if it doesn’t have quite the same ring.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.