Philadelphia residents are tracking air quality and pollution from their rowhouses in real time

With the fate of EPA regulations uncertain, advocates say local environmental protection efforts, like a community air monitoring network, are increasingly important.

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

At Tina Alishia Brown’s rowhouse in Southwest Philadelphia, Clean Air Council organizer Russell Zerbo ties a small white device to a post on the porch.

“You want it to be 5, 6 feet off the ground — an average person’s height,” he said.

Zerbo makes sure the device sits at “nose level,” because it’s measuring the air people breathe.

It’s one of 60 PurpleAir monitors the Clean Air Council installed this spring at homes and churches in Delaware County and South and Southwest Philadelphia, along the I-95 corridor.

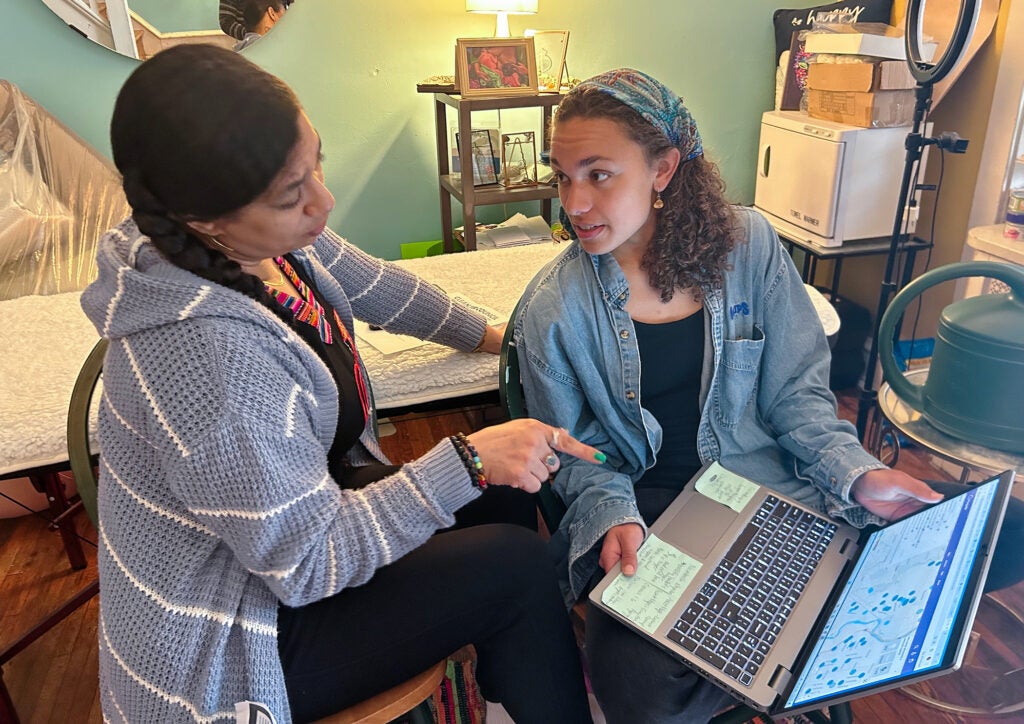

These monitors let residents track pollution coming from traffic, industrial facilities and construction sites in real time, said Jendaiya Hill, Clean Air Council community organizer. Then, neighbors can make decisions about how to protect their health — for example, by wearing a mask or postponing outdoor gatherings.

“Literally just like checking the weather,” Hill said.

Brown, the homeowner, has a 12-year-old son with asthma. She’s hoping the air monitor will help her keep him safe.

“I can just check it periodically to see how the air quality is and decide whether or not to keep my windows open or closed — or should my little one stay in for the day?” she said.

Filling in the gaps

Federal law already requires a network of thousands of government-run air quality monitors across the country. But Amanda Northcross, a professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering at the University of North Carolina’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, said this network is not dense enough to capture air quality on a block-by-block basis.

“It won’t tell you exactly what air pollution looks like within your neighborhood,” Northcross said. “If you live near a very high polluting source such as a freeway or a power plant, for example, looking at the closest [government] monitor near you commonly won’t give you much information about the kind of small-scale changes in air pollution that could be happening where you live.”

Northcross said community networks using PurpleAir monitors, like the one Clean Air Council installed, tend to be less accurate than the government monitors. But they’re good for filling in the gaps.

The Clean Air Council project is funded by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The agency terminated another grant the organization received to launch a similar air monitoring network near the Delaware City Refinery.

As the EPA plans to reconsider dozens of environmental regulations, Hill said local efforts like this one are increasingly important.

“No matter what’s happening on a federal level, in this area that we’re in, we can grow awareness and advocacy efforts around protecting our air — even if the structure of the EPA is not functioning in the ways that it previously was,” she said.

The PurpleAir monitors, like the one on Brown’s porch, measure fine particulate matter, a pollutant that can make symptoms worse for people with respiratory conditions, like Brown’s son. High levels can even trigger heart attacks for people with cardiovascular disease.

Community monitor data is publicly accessible

The monitors feed data to a publicly accessible, color-coded online map of similar monitors nationwide.

“If you go on there and all the dots are green, we’re having a great air quality day,” Hill said. “If you go on there and it starts being orange, anyone who has sensitive conditions — asthma, COPD, any kind of lung cancer or underlying health issues — may start to experience symptoms. Once you get into the red … that’s when it’s unhealthy for anyone.”

Brown is well aware of the ties between air quality and health, because she works as a doula — supporting pregnant people, who can be particularly sensitive to air pollution, through pregnancy, birth and the post-partum period.

Now that her air monitor is up and running, she plans to share information about the air on her block with her neighbors, as well.

“Some of us are so busy working and raising families that we don’t even think about air quality, until [an alert] flashes on the TV,” Brown said. “I’d love to be that person to just share — not to instill fear in anybody — just to inform and educate, just so we all can be aware.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.