For some wheelchair users, navigating Grays Ferry is a scene out of ‘Mad Max’

Illegally parked cars and crumbling sidewalks make for dangerous conditions for Philadelphians with limited mobility.

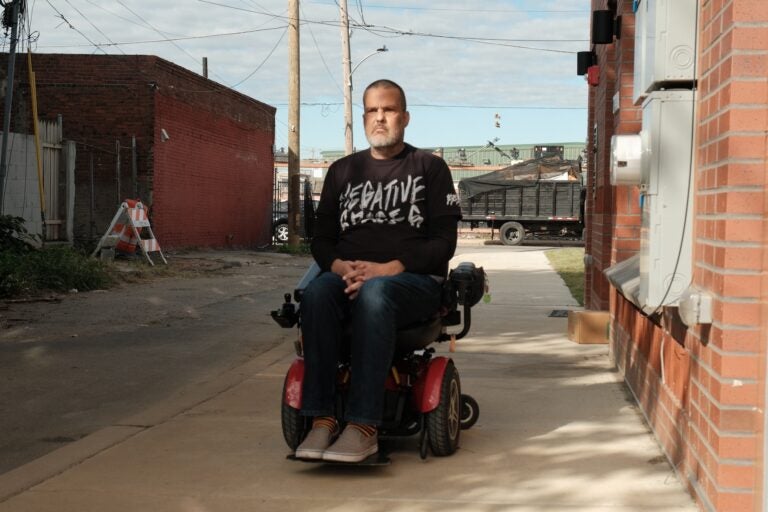

William Keiper lives in Grays Ferry. He says navigating Philly's neighborhoods in a wheelchair has "too much of a Mad Max feel." (Ben Bennett/WHYY)

Have a question about Philly’s neighborhoods or the systems that shape them? PlanPhilly reporters want to hear from you! Ask us a question or send us a story idea you think we should cover.

William Keiper sometimes can’t leave his apartment. The 48-year-old wheelchair user lives in housing designed for people with accessibility needs, a seven-unit complex on a small side street in Grays Ferry. Due to construction on the left side of the building, there’s only access to one curb cut.

When cars park and block the ramp, he has no way of getting from the sidewalk to the street. He has to call the police and wait for a tow truck.

“I’m held prisoner in my own home,” Keiper said.

Navigating Philadelphia’s neighborhoods poses a challenge for wheelchair users in the city. Illegally parked cars and crumbling sidewalks create a dangerous obstacle course for people with limited mobility.

Anywhere outside Center City, traversing sidewalks as a person with limited mobility is an arduous task, Keiper said. In South Philly, it’s common to see cars park practically anywhere — on corners, crosswalks, even sidewalks.

If a vehicle is blocking one of these pathways, wheelchair users like Keiper are left “defenseless.” To get around a blockade of cars, he frequently ends up in the street, which can create what he calls a funny situation.

“They seem to think they’re owed the sidewalks, but then they’re stuck behind me on the street,” Keiper said. “You like to block the sidewalk and force me into the street and now you have to be stuck behind me.”

How is Philadelphia helping wheelchair users?

It’s “unacceptable” for wheelchair users to be forced into the streets, said Nico Meyering, the chairman of Mayor Cherelle Parker’s Commission on People with Disabilities. He explained that earlier this year, the commission successfully worked to tow and ticket cars parking in South Philly.

In 2024, the Philadelphia Parking Authority announced a new campaign to ticket drivers that parked on sidewalks or blocked curb ramps. While the city saw a 500% increase in sidewalk parking citations, advocates still ask for more vigilance from the parking authority.

“We know that if we want people’s behavior to change, especially long term, then we need to keep up those long-term responses,” Meyering said.

Tess Galen said she “can’t imagine what it’s like for wheelchair users” who travel on city sidewalks. The Brewerytown resident has struggled to push her child in his stroller, often crossing the street to avoid obstacles like trash, cones and illegally parked cars.

Galen added that sometimes it’s not even an obstacle in her way that’s the problem — it’s the sidewalk itself.

“There are some places I walk where the sidewalk in front of someone’s home is completely torn up or missing,” Galen said. “Who’s responsible for that?”

When Philadelphia settled an Americans with Disabilities Act lawsuit in 2022, the city promised to build 10,000 curb ramps over the next 15 years. However, the city did not agree to do anything about the deteriorating state of the walkways. In fact, according to its definitions, Philly is not responsible for any sidewalk maintenance. Sidewalks in the city are private property and owners are held responsible “to maintain them in safe and sanitary conditions,” according to the city’s website.

“The city seems to be taking a position that not many other municipalities are,” said Rocco J. Iacullo, staff attorney at Disability Rights Pennsylvania. “Essentially, it’s all private responsibility for the sidewalks.”

By claiming that all sidewalks are private property, passing on the obligation of sidewalk and curb maintenance to building owners, Philly is trying to claim it’s “never their responsibility” to fix these walkways, even if they’re not ADA-compliant, Iacullo said.

“The city is trying to have their cake and eat it too,” Iacullo said.

The city of Denver had a similar situation with property owners being responsible for sidewalk maintenance. That is, until this year. In January, the onus of walkway repair was given to the city. In a new program, Denver will now repair and be liable for broken sidewalks, collecting a yearly $150 fee to fix them.

Philadelphia could follow Denver’s example and publicly fund sidewalk repair. Advocacy groups like Clean Air Council and Feet First Philly have campaigned for this kind of funding, but the city has yet to make any moves to do so.

Preparing for the U.S. semiquincentennial

With the 2026 World Cup and a host of other events set to bring millions of people to Philadelphia, disability rights advocates have demanded increased accessibility. The city is not only looking to make improvements to infrastructure around Lincoln Financial Field, but in neighborhoods, as well, according to Department of Streets Commissioner Kristin Del Rossi.

“Hopefully it leaks over here,” Keiper said when discussing the upgrades the 2026 happenings could bring. He said Philly’s neighborhoods seem to be an afterthought when it comes to accessibility issues.

“People in South Philly make it like a joke a lot of times, it’s just a South Philly thing,” Keiper said. “If they had to deal with it, they would lose their mind.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.