Lenape chiefs, Indian scholar reflect on Penn Treaty history

March 5, 2010

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

Two hundred years ago today, at what is now Fishtown’s Penn Treaty Park, a storm felled a huge tree that witnessed a promise of peace and friendship between leaders of two governments: one ancient, one newly born.

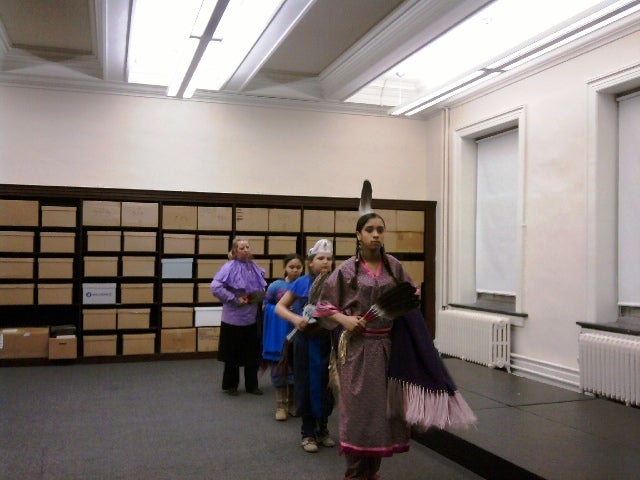

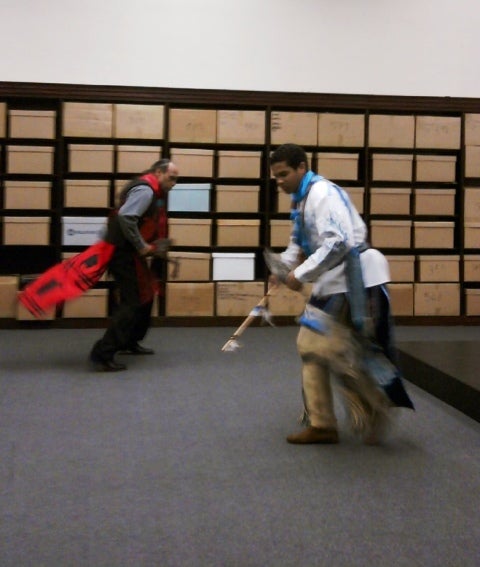

Thursday evening at the Pennsylvania Historical Society, descendents of Lenni-Lenape Chief Tamenend opened a multi-day commemoration of the fall of the Great Elm with drum beats and traditional dances, a swirl of colorful clothing and a message:

“We’re still here, and we are moving forward,” said Lenape Tribe of Delaware Chief Dennis Coker.

It’s been anything but easy, Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Chief Mark Gould told the crowd of about 200 who crowded the upstairs Center City lecture hall to learn more about the pact made by Tamenend and William Penn.

Gould, 68, said that when he was growing up, “it was not alright to be an Indian. The punishment that we went through, just for self declaration, it was horrendous.” He recalled his childhood in New Jersey, when his mother and other women would chase the children outdoors so they could speak of tribal ways that were then kept hidden, and of the wonder he felt seeing a photograph of his grandmother wearing a traditional headband.

“In about, I guess 1972, us young upstarts said that we’ve had enough of this,” Gould said. “We know our history. It’s been passed down. Why is it disallowed?” As they organized, the state government told them they would have to document their history to become a nonprofit organization. The large-scale history of the people was easy, Gould said. “It had been handed down to us.”

‘Where’s the gold?’

Personal histories were not as well known. “The most generous thing that the governor did to us was to make us do our genealogy,” he said. And so the making of families – often by cross-river marriages between Gould’s portion of the Lenape and Coker’s – was traced.

Native American history expert Gregory Schaaf, director of the Center for Indigenous Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and himself part Cherokee, called it an “act of the Creator” – a miracle – which the Lenni-Lenape people are still here. The 1682 treaty of friendship between Lenape Tamenend and Penn (then the colonial governor as well as a Quaker) was broken, and the Lenape and other native people were displaced, exploited, and worse.

But the message of the treaty still resonates, said Schaaf, the evening’s keynote speaker. He said that Penn and the Quakers respected the Lenape as a people. Other colonial American people would do unspeakable things, like kidnapping Native American children and taking them to Europe, he said. Largely, Schaaf said, they wanted to teach the children Spanish or French or English, so they could act as translators to ask their tribes a golden question: “Where’s the gold?”

Schaaf surmised that part of the Quaker’s respect and desire to understand the Lenape came from the fact that they, too, had been persecuted for being different.

‘Holy Grail’

Although Thursday night’s events, and those that continue through the weekend, are focused on history, organizers hope the discussion of the Treaty of Friendship will inspire people who hear it to embrace and fight for its principles: fairness, peace and social justice.

At least one Quaker leader has already been inspired.

Thomas Swain, clerk of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Quakers, said in a telephone interview Friday morning that he felt honored and inspired to meet Gould. He hopes the two of them can use the tenets of the 300-year-old treaty to work together on a very contemporary problem.

“When I see him, I’m going to ask the chief if there is anything about the care of the earth in the treaty,” he said. “I’d like to see if he and I can use the Treaty as a launch pad for some cooperative things, like keeping the concern of climate change at the forefront.”

Swain hopes to see Gould at a Saturday afternoon ceremony at Penn Treaty Park. There will also be a special Quaker meeting earlier in the day. Friday afternoon, a lecture at the Philadelphia Flower Show was to include discussion of the Great Elm itself. For a full schedule of events, visit the Penn Treaty Museum web site, http://www.penntreatymuseum.org/.

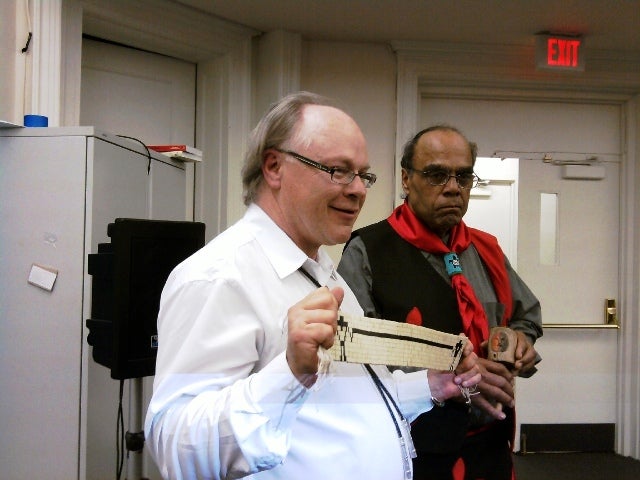

On Thursday evening, Schaaf’s lecture was as much show as tell.

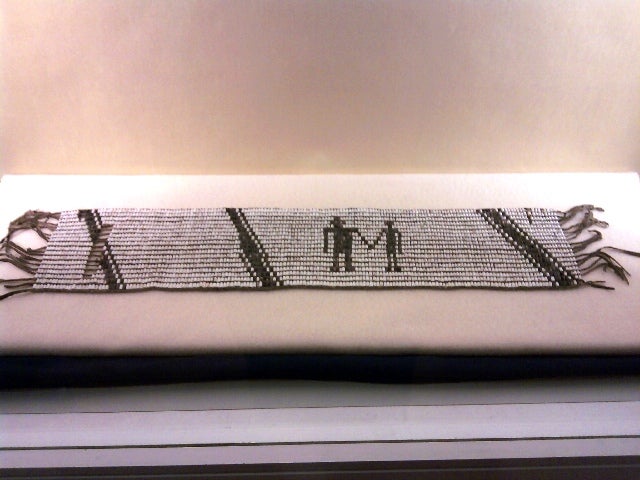

He passed around photographs of Indian artifacts and replicas of wampum belts, including one given to George Washington.

He spoke reverently of the wampum belt Tamenend gave to Penn, calling it “the Holy Grail for the original people of this land.” It is usually housed at the Atwater Kent Museum, but was brought to the Historical Society for Thursday’s event.

“It’s like the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution – the original – is for we the people of the United States,” he said.

‘Our future, our hope’

Schaaf described meetings he had with Lenape elders who were still fluent in their original language, but told him in English of the history of their tribe. Way, way back in this history is a story of the Great Flood, similar in ways to the Judeo-Christian story of Noah. But here, the ark is a giant turtle. And it is the heroics of a muskrat that allow the earth to be reborn. The elders told him of 100 generations before the coming of the Europeans, he said.

Schaaf also spoke of the influence Native American systems of government had on establishing the United States government. He helped prove this to Congress, which passed legislation recognizing the impact. But much more work needs to be done, he said. Most school children are still not learning this history in school, he said.

From his satchel, Schaaf removed an object and unwrapped it. It was a carved wooden rattle, used in a ceremony in which Lenape sung their dreams. He asked a young girl from the audience to come take a closer look. “She is our future. She is our hope,” he said.

If that little girl learned the teachings of Gould and the Lenape, her descendents would have respect for Gould’s descendents, Schaaf said. And the message of the treaty reached at the place Native Americans called Shackamaxon would continue with future generations.

View more dancing and the entire lecture via the following links:

Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape dancers perform.

Lenape Duncan Munson demonstrates a grass dance.

Tanya Norwood introduces Chief Mark Gould, who speaks about fighting to have his culture recognized.

Chief Gould and Delaware Lenape Chief Dennis Coker.

Native American scholar Gregory Schaaf on the treaty, wampum belts, and Native American history.

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.