Reawakening Pennsylvania’s forgotten whiskey history

During the 1800s, Pennsylvania was at the epicenter of the rye whiskey industry. Prohibition caused most of the distilleries to close, and the state’s legacy was forgotten.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

A pungent and sour scent reached every corner of Dad’s Hat whiskey distillery as rye and malt bubbled away in a fermenter.

Herman Mihalich poured amber-hued liquid from a tall silver tank into a ladle. He took a sip, smacked his lips gently and exhaled: “Delicious.”

After leaving the fragrance ingredients and chemical industries, Mihalich embarked on a mission to bring rye whiskey back to Pennsylvania.

He and his friend John Cooper opened their “farm-to-bottle” operation in 2011 inside a former textile mill in Bristol. They source grain from a local Bucks County farm to produce whiskey at their distillery, which sits near the Delaware River.

The name Dad’s Hat is a nod to Mihalich’s father, who styled himself with fedora hats and enjoyed drinking rye whiskey at the family-run bar.

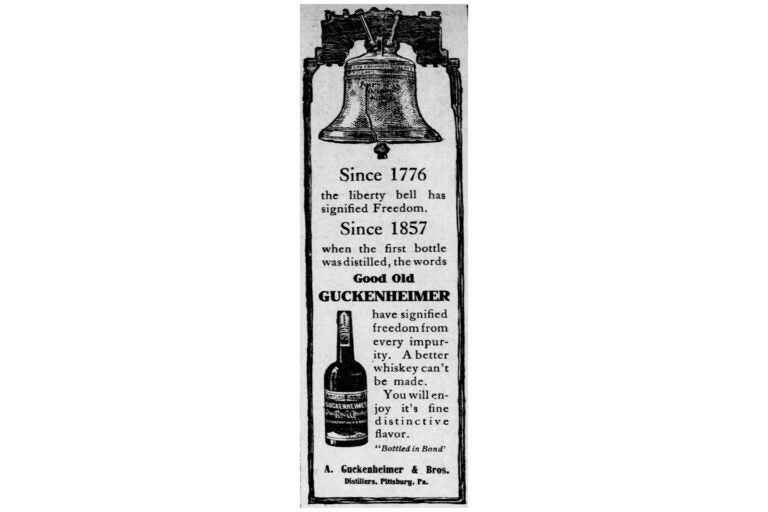

Rye whiskey was established in Pennsylvania in the 18th century, and by the 1800s there were hundreds of distilleries near the Monongahela River. The reddish spirit was so renowned, Herman Melville used Monongahela rye as a metaphor for the whale’s spurting blood in his novel “Moby Dick.”

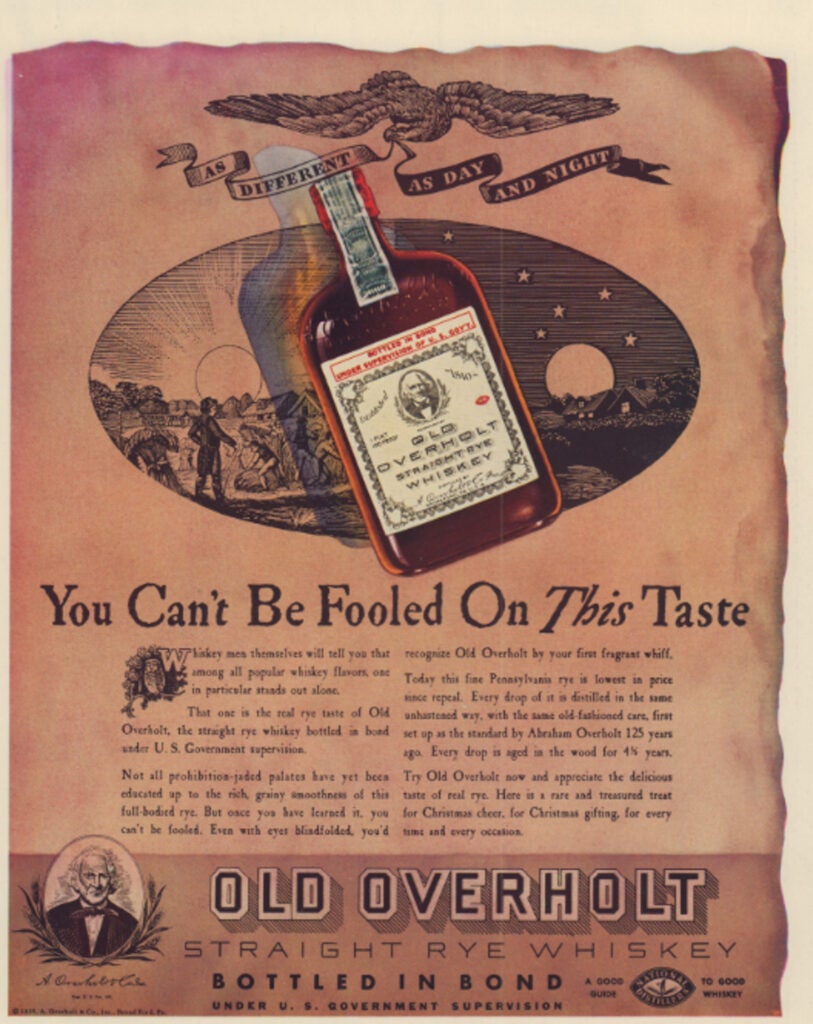

But Pennsylvania’s whiskey industry did not survive prohibition, and its former glory was forgotten in time. The state’s once famous rye whiskey brands Old Overholt and Michter’s, historically known as Bomberger’s, are now made in Kentucky.

However, the style of Pennsylvania whiskey is going through a renaissance, and distillers like Dad’s Hat hope to put the state back on the map.

“It’s hearkening back to the heyday of Pennsylvania rye whiskies,” Mihalich said. “We’re practicing that old recipe, the 80% grain and 20% malt. We’re doing it in an updated way with a still from a company who’s been making stills for 150 years.”

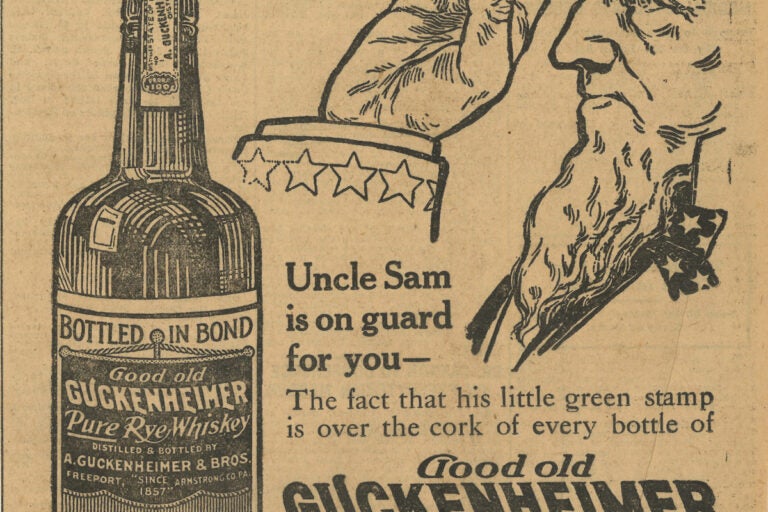

A ‘patriotic’ drink

European settlers introduced rye to North America, where the hardy grain was established as a cultivated crop.

In the late 1700s, Pennsylvania farmers used their excess rye to make whiskey, which was a more dense and valuable product than grain. Rye whiskey was primarily used as a bartering tool, and was traded for livestock, goods and services like blacksmithing.

“You can carry eight mule loads of grain, or you can carry one mule load of whiskey,” said Lew Bryson, a local whiskey writer and historian.

As the United States distanced itself from British identity following the American Revolution, rye whiskey became a national beverage.

“Post-Revolutionary War, you had this rejection of rum and molasses, and British products. American made products, namely rye whiskey, stood out as almost a patriotic thing to drink,” said Laura Fields, a local historian known for her American Whiskey History Facebook page.

In 1790, Alexander Hamilton, then the U.S. treasury secretary, proposed a whiskey tax to help pay off the nation’s war debt. Under the new law, larger whiskey producers in eastern Pennsylvania could pay the tax annually at a lower rate per gallon and were rewarded with tax breaks for higher volumes. Meanwhile, smaller producers in the west were left paying higher taxes. The law also required the taxes to be paid in coins, which were sparse on the frontier. Farmers in western Pennsylvania believed the tax unfairly targeted them, while making them less competitive with wealthier eastern grain producers.

Resistance to the tax ultimately led to violent protests known as the Whiskey Rebellion, and in 1794, George Washington sent a militia to stop the rebels. The whiskey tax was repealed under President Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

During the 19th century, rye whiskey was no longer a product of small farmers supplementing their incomes — it became an industry, and Pennsylvania was at the epicenter.

“This was a big industry because there was a lot of money-making potential in it, and it was actually a very simple industry,” said whiskey historian Sam Komlenic.

‘A nectar fit for the gods’

Growing up near an abandoned distillery southeast of Pittsburgh, Komlenic became fascinated with Pennsylvania’s forgotten whiskey history. He has researched the topic extensively, and has collected more than 200 historic whiskey bottles by scouring eBay.

Komlenic has donated most of his collection to West Overton Village and Museum, the birthplace of Henry Clay Frick, who owned Old Overholt, widely recognized as America’s oldest rye whiskey.

Komlenic lights up as he shows off his at-home collection of 19th-century bottles. Whiskey labels depict images of prominent Pennsylvania distilleries and their tall smokestacks. One label simply describes the bottle’s ingredients: “Monongahela Rye Whiskey.”

“That’s all you needed to know,” said Komlenic, a former board member at West Overton Village. “It didn’t matter what distillery it came from. The fact that you were getting Monongahela rye whiskey, much like you’re getting Kentucky straight bourbon, was an important thing.”

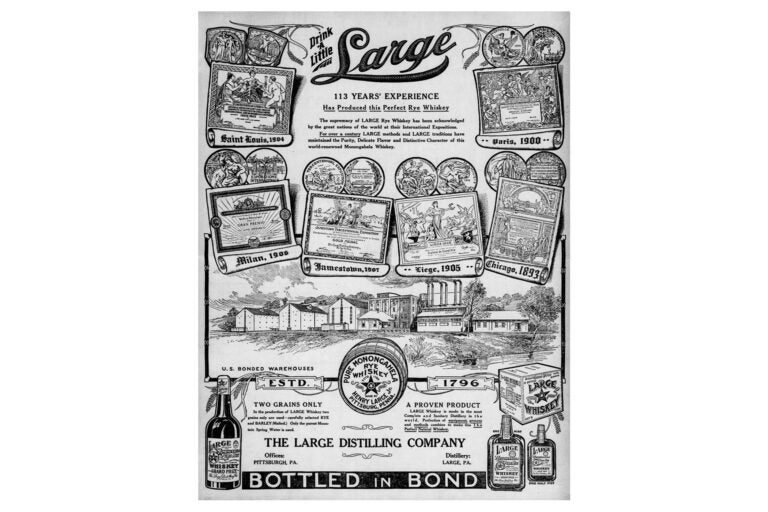

Monongahela rye was produced in southwestern Pennsylvania along the Monongahela River and its tributaries. The style, which historically was often produced using three-chamber stills, is notable for its rye and malted barley ingredients, and a sweet mash process as opposed to a sour mash. The result is a drink with a rich and full-bodied flavor profile.

In 1892, the Pittsburgh Dispatch described the Monongahela Valley as the “Mecca of Distillers.” A few years later in 1899, the Ligonier Echo informed readers that there was no other place in the world from which “as much whiskey is shipped in one week as is sent out of Western Pennsylvania.”

Among Pennsylvania’s popular distilleries were Samuel Thompson, which, according to family legend, was won in a poker game — or because of a debt by other accounts — and Gibson’s distillery, then one of the most prominent whiskey distilleries along with Old Overholt.

There was also Phillip Hamburger’s distillery, which produced Old Bridgeport. In a 1914 article for a trade publication, Hamburger’s business partner Albert Hanauer romanticized what he described as “a nectar fit for the gods.”

“Inhale its exquisite aroma; enjoy its superb bouquet; it brings to the mind’s eye the smiling rye fields, the rye waving joyously in the sun, and the troop of happy children passing through,” Hanauer wrote. “Look again, and the liquid amber, coupled with the word Monongahela, bring remembrances of George Washington and the stirring days of the whisky insurrection.”

But prohibition halted production, and distilleries closed down. Their equipment was removed and sold for scrap value, and many of the buildings began to decay.

The rye whiskey industry in Pennsylvania could not survive the impacts of prohibition. Laura Fields partly attributes this to significant consolidation efforts that shut out independent distillers, a lack of corporate support and an inability to protect assets. Some local distillers also died by the end of prohibition, and there were no apprenticeships during that time, she said.

Only a few distilleries reopened in Pennsylvania after prohibition ended, Komlenic said.

“We did this to protect our families. Women were being beaten by their drunken husbands. Women were a huge factor in prohibition, as was the Methodist Church,” he said. “They all had lofty goals in mind, but they did not realize the draw of an illicit product.”

Michter’s was the last remaining Pennsylvania distillery until it closed in 1990. A print image of the distillery now hangs above a cabinet in Komlenic’s home office.

The rebirth of Pennsylvania rye whiskey

In the past decade, Pennsylvania rye whiskey has made a comeback. There are now about 150 distilleries in the state and 21 of those specialize in Pennsylvania rye.

“We’re truly living in some of rye whiskey’s headiest glory days right now,” Komlenic said. “We’re not making nearly as much of it as we used to, but it’s much more a part of the national consciousness than it has been for decades.”

At the Stoll & Wolfe distillery in Lititz, co-founder Erik Wolfe uses rye and malt from a farm that has been in his family since 1741. The farm is so close to the cozy distillery that the grain is delivered by tractor and wagon. Bricks from a nearby 18th-century distillery hold up the stills inside Stoll & Wolfe.

Wolfe, a self-described history and whiskey geek, said he feels a great deal of responsibility to uphold the legacy of the past while producing a product for the modern palate.

He opened the business in 2017 with the late Dick Stoll, who in the 1970s and ‘80s was a master distiller at Michter’s. Stoll & Wolfe emulates the distilling techniques used at Michter’s, including using a wooden vat for an open fermentation process.

The distillery’s use of technology — using both a column still and a pot still — is more modern than colonial distilling. However, the same scientific principles for making whiskey still apply, Wolfe said. The distiller has even produced rye whiskey based on a written recipe from a journal kept by a colonial distiller in Pennsylvania.

“For us it’s really about just creating flavors that are spanning that 300-year legacy and giving modern consumers a chance to appreciate something that’s historic, but also is produced in such a way with modern production that it’s still appealing to modern consumers as well,” Wolfe said.

Similarly, at Dad’s Hat in Bristol, Herman Mihalich also has a passion for authentic Pennsylvania rye whiskey. The distillery sits along the Delaware River where limestone quarries are a source of calcium and magnesium. The minerals contribute to the drinking water’s hardness and are important for yeast health during alcohol production.

“It’s as good as any mineral water you’ve ever had because when we first started, we actually tested the local water and found it to be excellent in terms of its hardness,” Mihalich said. “So that limestone and the rock formations we’re standing over contribute in a really positive way to the quality of the water we’re using.”

At least three gallons of water is used to make every gallon of whiskey. Following a grinding process, grain is mixed and cooked with hot water in a large tank. The enzymes in the malt break down the starch into sugar, which along with yeast, is converted into alcohol.

Kentucky bourbon distillers also boast their use of limestone water, but it’s not essential. In fact, most Scottish distillers use soft water to make their whisky.

As for Pennsylvania rye, what makes it stand out is its spicy and herbal character, with whiskey writer Lew Bryson describing its taste as clove-like in nature, depending on the yeast.

“It usually comes out with some grassy notes, might be minty. But it’s a much more herbal, spicy character than most bourbons,” he said.

While it’s making a comeback, the spirit hasn’t reached the same following it achieved in the 1800s. Locally-produced rye whiskey is one of the least ordered items on the menu at Bank & Bourbon restaurant and whiskey bar in Philadelphia, despite efforts to promote it, said Daniel Rivas, director of food and beverage.

“A good part of that is education, and a lot of these brands don’t have recognition across the general consumer,” he said. “People associate whiskey with bourbon and Kentucky, and that’s just been the buildup of marketing campaigns over decades where people are gravitating towards the larger brand names.”

The Pennsylvania Distillers Guild wants to create standards that would define Pennsylvania rye’s ingredients and proof, as well as how it’s made. Distillers and whiskey lovers say if implemented fairly, that could help the state reclaim its heritage, in the way Kentucky has with its bourbon.

“I think residents of Pennsylvania should be juiced up about the role of Pennsylvania in American whiskey history, the quality of whiskey being produced here in Pennsylvania,” said connoisseur Michael Krancer. “We have such a rich tradition of whiskey coming out of Pennsylvania that we as Pennsylvanians should be having some Pa. bottles on our shelf.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.