Penn ramps up addiction research that could help doctors tailor treatments

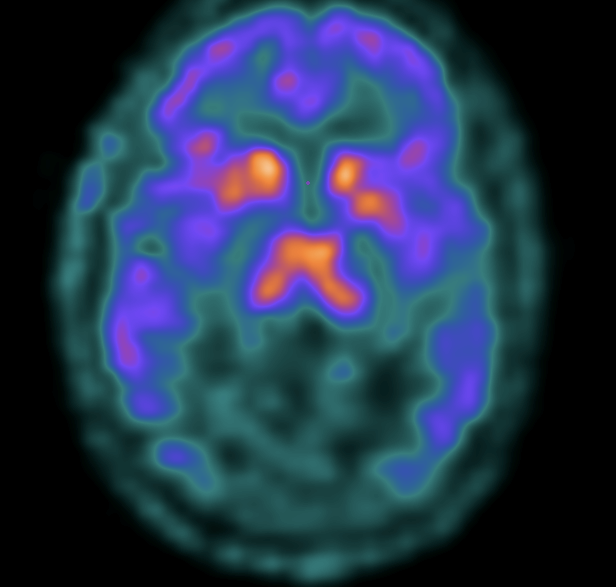

The PET Addiction Center of Excellence will use PET scans to peer inside the brain, allowing for the study of opioid receptors’ function in different individuals.

PET brain imaging of an opioid receptor binding. (Penn Medicine)

The University of Pennsylvania is opening a new research center that could help doctors figure out which treatments will work best for people suffering from opioid addiction.

The Penn PET Addiction Center of Excellence (PACE) will use PET scans to peer inside the brains of these patients, allowing scientists to home in on the opioid receptors to see how they function in different individuals. Using this molecular picture, the Penn researchers say, they’ll be able to conduct studies that could one day help doctors predict how well someone might respond to different medications to treat opioid addiction, such as methadone or Suboxone.

“The more we understand the biology of opioid dependence and opioid effects in the brain, the better able we are to identify new medications that have perhaps fewer adverse effects, and the better we will be able to identify specifically for whom each medication might be optimal — a precision medicine approach,” said Henry Kranzler, director of Penn’s Center for Studies of Addiction and co-principal investigator at the new center.

With opioid overdoses having killed nearly 50,000 people nationwide in 2018, he said there was a critical need for coming up with better treatment approaches.

For example, he said, some people have genes that have been shown to predict how well they will respond to treatment with buprenorphine, the active ingredient in Suboxone. One research proposal would study the biological mechanism that may be responsible.

“It would enable us to validate the genetic biomarker that could be used clinically to identify people who are most likely to be good responders to buprenorphine,” Kranzler said.

PACE is the first research center dedicated to using positron emission tomography scans to study opioid addiction. While brain imaging is now a common tool used by scientists to study addiction, very little of it is done using PET scans, said Jon-Kar Zubieta, a professor of psychiatry at Stony Brook University who is not affiliated with the Penn center.

Zubieta, who has been using PET scans in his research for two decades, said the vast majority of neuroimaging studies of addiction use another technique, functional MRI, that is less expensive and easier to use. But those images don’t allow scientists to observe the receptors, neurotransmitters, and proteins in the brain that are involved in addiction, he said.

“That’s very important,” Zubieta said, because it can help researchers understand variations among individuals, such as “why one individual may be prone to develop an addiction and another one may not.”

Zubieta said this kind of molecular research has been key to advancing treatments for other deadly diseases.

“A lot of money has been spent doing that, and the result has been that cancer, of all things, has the capacity of being treated in a personalized fashion. That has never happened in the field of addictions,” he said.

There are only about four academic centers in the world using this technique that could help personalize addiction medicine, he noted.

Kranzler said that the five-year, $8.9 million grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse funding PACE will allow Penn to quadruple its capacity for PET-based addiction research. Some of the money will also go to researchers at Yale University, which is collaborating on the new center.

Researchers would study common co-occurring conditions in people with opioid use disorder, such as high suicide risk and HIV.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.