Penn Museum’s new Native North America exhibition collaborates with Indigenous curators

Eight curators from eight Indigenous nations redesigned Penn Museum’s Native North America display.

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Jeremy Johnson worked for more than two years to help Penn Museum rethink its Native North American exhibition.

A member of the Delaware Tribe of Indians, also known as the Lenape, Johnson said that when he finally saw it come together, he got emotional.

“What you see on display are not just items,” Johnson said, then paused to compose himself. “They’re my relatives.”

Johnson is one of eight curators from eight Indigenous communities around the country who collaborated with Penn Museum. They represent the tribes of Delaware, Muscogee Creek, Eastern Band of Cherokee, San Ildefonso Pueblo, Zuni Pueblo, Santa Clara Pueblo, Ninilchik and Tlingit.

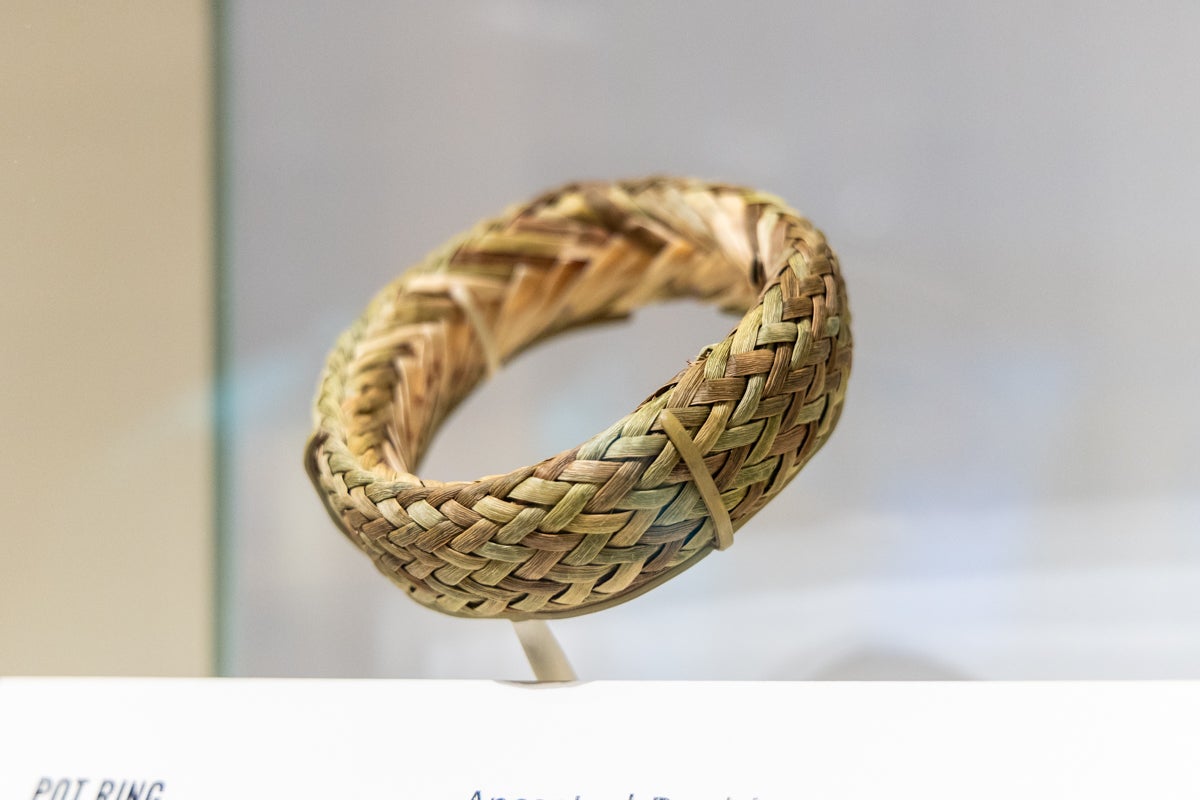

They worked closely with museum staff to decide which items were appropriate for display and which were not for public viewing. They decided how to put ancient objects alongside contemporary Indigenous objects. They decided what the stories the objects should tell.

Johnson wanted the exhibition to highlight that ancient objects, some of which are several thousand years old, represent people and customs that are present and alive today.

“They’re not artifacts,” he said. “They’re living items that have a life and have knowledge contained within. Eons of knowledge contained within them. To be able to express that in the way that we have here, I think it’s been a blessing.”

The cohort of curators were even consulted on details like the exhibition’s color palette and marketing materials. RaeLynn Butler, of the Muskogee Creek Nation, said no museum has ever asked this much of her.

“We would get a museum that will send a picture of an object and text, ‘This is what we’re going to put up. Do you approve? Checkmark, yes,’ and not even include our tribal name” she said. “This is going a step further than other exhibits have gone in the past with a level of collaboration.”

The four corners of the gallery correspond with the four corners of the country. The Northeast focuses mainly on the Lenape, the Southeast features Eastern Band Cherokee and Muscogee Creek, the Southwest has the Pueblo, and the Northwest is oriented around Alaska and the Tlingit and Alutiiq people.

All of the exhibits discuss the detrimental effects the arrival of Europeans caused on the tribes. The display of Cherokee and Muscogee, for example, describes the ethnic cleansing act known as the Trail of Tears when they were forcibly removed from the Southeast and relocated around the Mississippi Valley.

The Northwest section describes the acquisition of Alaska as a territory in 1912. Citizenship for native people, which allowed for things like education and land ownership, required them to give up all tribal customs and relationships.

“We have a section in the middle that talks about the moment of rupture, the moment of colonialism that each of these communities face. But what that says is dramatically different for each community,” said staff curator Megan Kassabaum, an associate professor of anthropology at Penn.

“The structure allows us to put those stories in parallel without homogenizing the story across North America,” she said.

Given pride of place in the exhibition on a wall panel visitors immediately face as they enter the room is a display that speaks loudly for being silent: A glass case holding nothing.

That conspicuous absence represents objects in the Penn collection that the curators decided are not appropriate for public view.

“There are certain things that are for our people that we share and we openly share,” Johnson said. “And there are things that we don’t want to share because they are just for us.”

In the exhibition of the Cherokee people, the wall text says Penn Museum repatriated many objects to the Cherokee in 2013 and 2018, but the two parties continue to be in disagreement over additional objects, per the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

In deference to the Cherokee, no items in disagreement are on public view. Instead, there are undisputed objects associated with Will West Long, a late 19th- to early 20th-century Cherokee who worked with institutions for the preservation of Cherokee culture.

The exhibition commissioned contemporary Indigenous artists and artisans to make original work for display. Among them is “I Am More Than Fluff,” a bronze figure in a glass bell jar stuffed with feathers. Artist Holly Wilson, of the Delaware Nation, describes the piece in opposition to the idea that Indigenous people are “lost to a romanticized ideal of who the Native Americans were.”

“I am more than the view that my people are frozen in time,” she said.

Another contributor to the exhibition, Bradley Hicks, of the Muscogee Creek, made stickball sticks. Unlike the sport once commonly played by urban kids in Philadelphia streets, the Muscogee stickball is more similar to lacrosse, going back thousands of years.

Hick’s hickory sticks are made in the traditional way, with strips of wood steam-bent into a small basket on the end and tied with leather straps. They are displayed next to remarkably similar sticks made 1,000 years earlier.

The game is played with each player holding two sticks, one in each hand.

“The object is to get the ball and throw it between these two goalposts. But it’s a pretty rough game,” Hicks said. “We tend to get hit with the sticks, whether it be in the hands or the head. But growing up playing from a baby, we just get used to it. It’s part of the game.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.