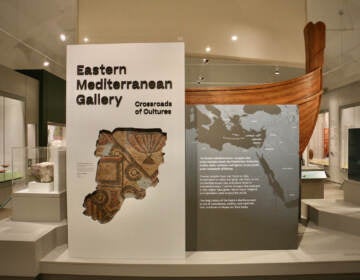

Penn Museum shows what ancient worlds tasted like

“Ancient Food and Flavor” features rare artifacts of food to show what people ate millenia ago, and how it tasted.

"Ancient Food and Flavor" at the Penn Museum features outdoor raised beds with plantings of the types of foods that would have been in ancient Peru, Switzerland, and Jordan. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

Llama jerky, burned raisins, 6,000 year-old dried apples, and ancient blackthorn berries.

Food, glorious food!

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology often shows objects that were used to store food, tools for preparing food, and ceramics of consuming food, but rarely does it show visitors actual foodstuff — the things ancient people would eat.

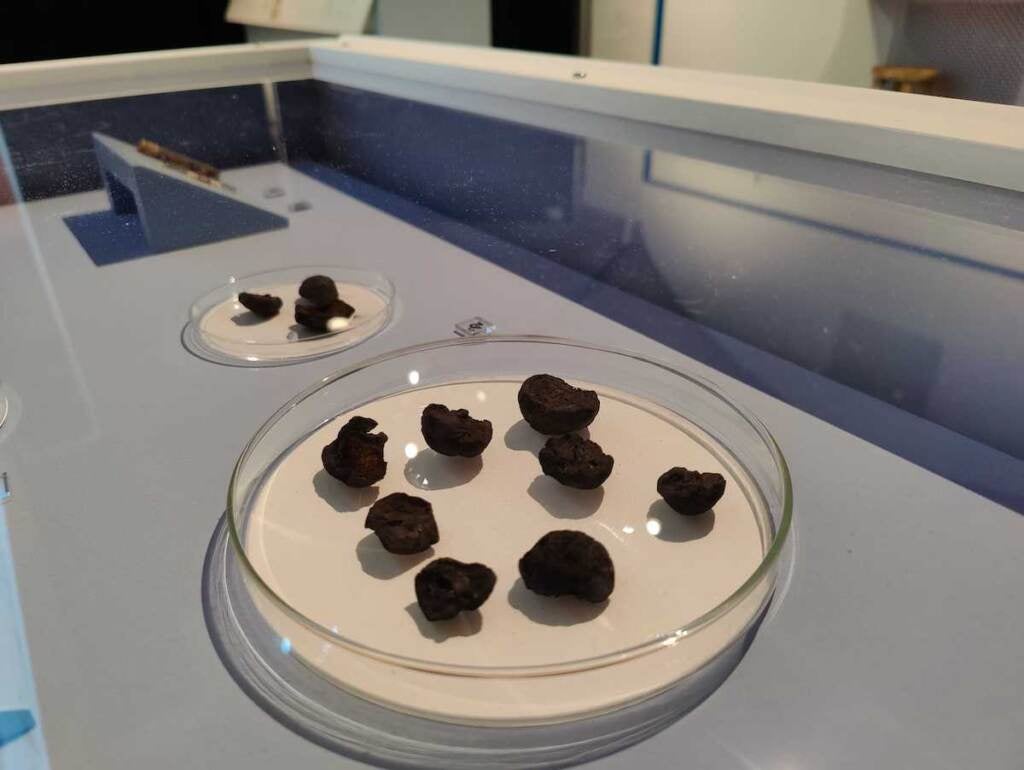

That’s largely for two reasons: Unlike artifacts of ceramic, stone, and bone, food generally does not survive millennia. Also, food that is able to survive hundreds or thousands of years does not make for showstopping museum objects: It’s hard for a handful of seeds and a few pellets of burned fruit to compete with, for example, a gilded funeral headdress.

Nevertheless, the Penn Museum has been collecting and cataloging food for more than a century.

“Just the fact that we took food remains from those sites and saved them, is a triumph of museum practice,” said Co-curator Katherine Moore, a teaching specialist for zooarchaeology and Penn’s undergraduate chair of anthropology. “They’re non-elite. There’s no golden headdress. Just the intrinsic interest of thinking about how those people stayed alive was enough for people to collect and maintain those records.”

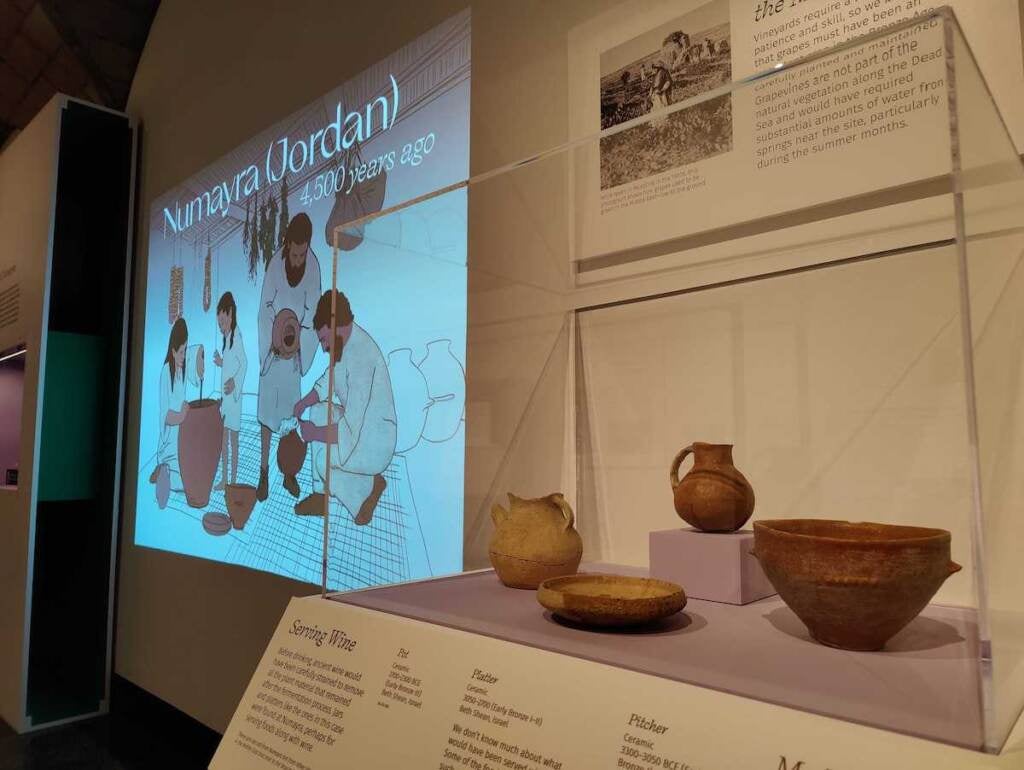

The new exhibition “Ancient Food and Flavor” is a banquet of less sexy objects that played a huge role in ancient societies. It focuses on three archeological sites that gave up unusual amounts of food artifacts: Robenhausen in Switzerland, a 6,000 year-old former wetland where water preserved food such as flax and apples; Pachacámac in Peru, about 600 years ago, where the dry climate acted as a preserving agent; and Numayra in Jordan, destroyed by a sudden fire 4,500 years ago that scorched everything into a state of preservation.

The exhibition features what looks like dried pellets which, on closer inspection, turn out to be tiny apples that were cut in half to be dried and stored for future meals. There’s also flat rinds of the lucuma fruit of the Andes mountains, and grape seeds likely leftover from winemaking in Jordan.

The objects may not be mouthwatering to look at — a vial of goat dung is among the artifacts — but with some archeological research and a little imagination the flavor profiles of these ancient people can whet the appetite.

Moore combines what archeologists know about the spice routes of ancient global trade with the physical record of foodstuff artifacts to come up with tastes.

“We know where every peppercorn was dropped from Indonesian to Holland over the course of 500 years,” she said.

In Switzerland, for example, apples were abundant and likely combined with meat to lend sweetness and tartness to savory dishes.

The food in Peru was probably not like Peruvian cuisine as it is known today, because things like onions and garlic — the basis of many savory dishes — would not have been available at the time.

“And, of course, pre-Columbian societies of all kinds had no dairy foods,” Moore said. “Forget cream and cheese. So you’re left with fruit and chili peppers, and the tanginess of some of the root foods — ones you’re probably less familiar with like yuca and ulluco and ñame.”

The ancient foods of Jordan were likely somewhat similar to the Mediterranean flavors familiar today. Ancient Jordan had barley, grapes, figs, coriander, and mint. The presence of chickpeas and sesame seeds in the ancient record suggest hummus has been a staple of the Middle East for a very long time.

But there weren’t any lemons in Jordan 4,000 years ago. Tomatoes did not appear in Europe or the Middle East until they were brought back from the Americas by explorers.

“I’ve spent a lot of time, as many culinary historians have, trying to figure out what the food of the Mediterranean and the Middle East would have tasted like without tomatoes,” Moore said. “Archeological records suggest that a lot of that tang and sweetness would have come from apricots, which is a tree that grows in a wide variety of warm and dry environments.”

Visitors to “Ancient Food and Flavor” can take home recipes to explore these flavor profiles at home, although the recipes are derived from modern sources that suggest ancient dishes rather than recreate them. From Jordan is a farro grain pudding recipe made with pistachios and honey, for example, and apples baked with a hazelnut marzipan from Switzerland.

From Peru, the exhibition offers a recipe for a Peruvian shrimp chowder made with native corn and peppers, but also with onion and cream which was unknown in the Andes two millennia ago.

“Ancient Food and Flavor” opens with food-related activities on Saturday June 3, and will remain on view until fall 2024.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.