Penn, Jefferson expand at-home cancer treatments during COVID-19 pandemic

People are trying to follow social distancing guidelines, so health systems are trying out bringing cancer treatments to their patients’ homes.

(MKrivonos/BigStock)

Every month for the past five years, Desiree Harmon would go to the hospital for an injection to treat her breast cancer.

“This every-four-week appointment was my calendar-killer, because everything else had to revolve around myself going in … every four weeks for this very important treatment.”

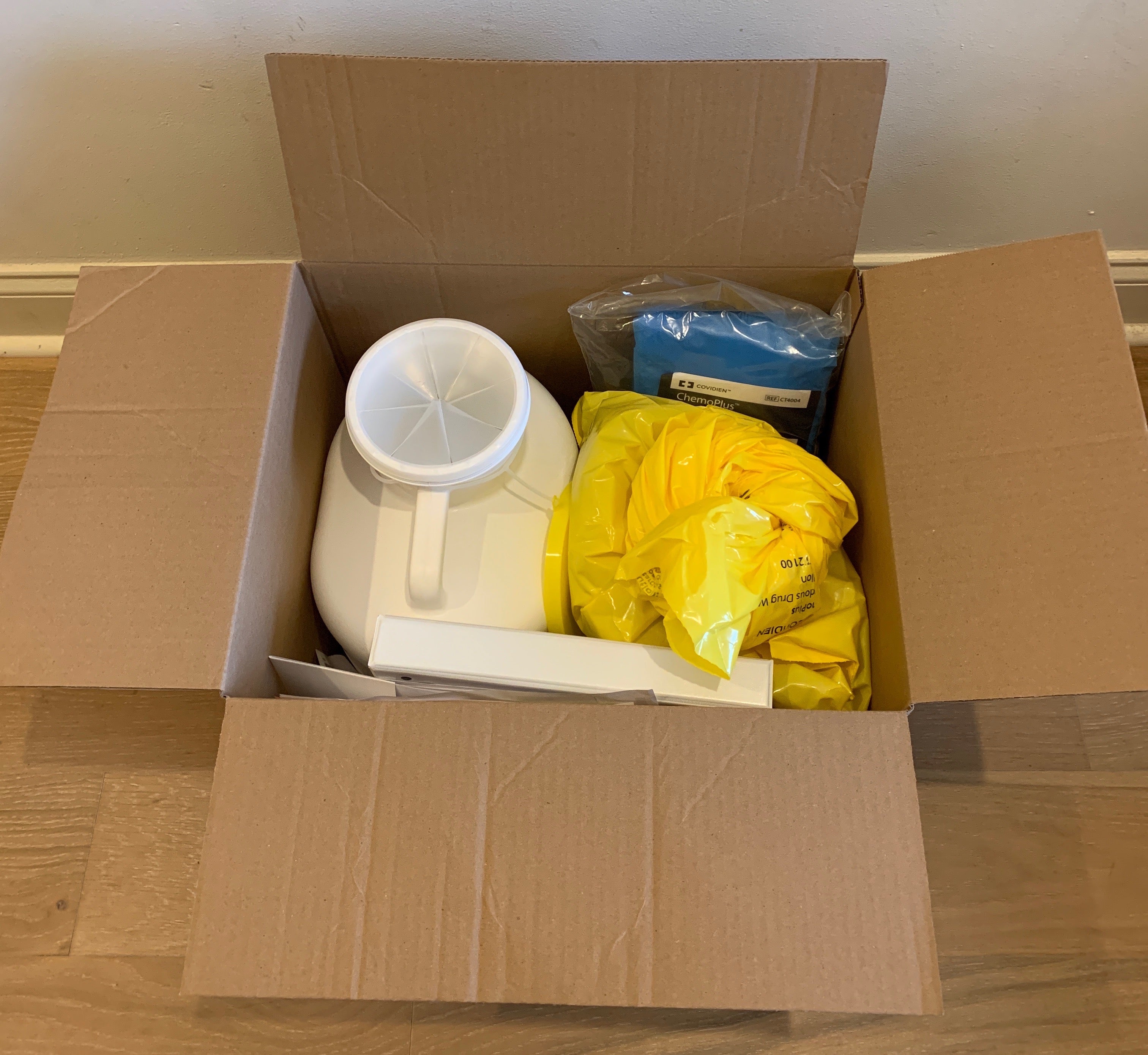

Last month, she joined a pilot program, in which medical staff would send over the medicine and all the necessary equipment — such as a sharps container, gloves, and a binder of patient information — and then a nurse would come to Harmon at home or work to deliver the injection.

To Harmon, that seems especially prescient now because she, like many other people, has been staying home and not going outside unless absolutely necessary.

Penn Medicine and Jefferson Health had already started pilot programs to treat cancer patients at home, and they are expanding those programs now that patients are following social distancing guidelines.

Some cancer patients, as well as patients with other conditions, get their medicine by infusion, which means it goes into their veins through needles. Before the current COVID-19 pandemic, about 1,850 patients were getting their infusions at home per day, and that number is up to almost 2,000, according to Joan Doyle, executive director of Penn Medicine’s home care and hospice service.

More specifically for cancer, around 100 patients at Penn already get the treatments at home, and the number is expected to increase several-fold in the coming weeks, said Justin Bekelman, director of the Penn Center for Cancer Care Innovation. He said the pandemic has had the side effect of accelerating innovation in this particular area.

“Cancer care can’t just stop,” Bekelman said. “We have to think about ways to either move ahead with treatment in alternative locations, bring patients into the hospital in a safe way … or in certain circumstances … delay if appropriate.”

Adam Binder, assistant professor of medical oncology at Thomas Jefferson University, said his team has also been expanding its home-based chemotherapy program since the pandemic, because more patients have asked for it.

“Patients are calling up wondering if they really have to come in. Some patients are … cancelling even if their providers are encouraging them to come in for their treatments, and so there’s a real need to meet the patients where they’re at and provide care in their homes,” Binder said.

However, not all cancer treatments can be given at a patient’s home, and medical teams have to figure out logistical issues as well.

For example, the pilot programs thus far have involved drugs that are relatively safe, well-understood, and easy to deliver. Binder said some other chemotherapy drugs are highly regulated, and normally medical staff would do two independent checks to make sure the right patient is getting the right drug in the right dose. Without sending two different nurses to each patient’s home, how would that check work?

If a home infusion service does not use the same kind of electronic medical record as the patient’s health care provider, is there an easy way to track how much of a particular drug a patient has gotten over time? For example, Binder said, some cancers are treated with the drug doxorubicin, but doctors have to track how much of it a patient has gotten over a lifetime because it can lead to life-threatening heart problems.

In a way, home cancer treatment is an outgrowth of a program from Johns Hopkins University called Hospital at Home, which doctors first tried in the 1990s. Bruce Leff, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, led some of the early research on this idea. He said he has also been getting a lot more calls from interested health systems these days.

“Even before this pandemic, I was taking between three and half a dozen calls a week just from health systems wanting to learn more about Hospital at Home,” he said. “In the context of the pandemic, that interest has gone up even a bit more.”

Leff said he could see such programs being useful in taking people who don’t have COVID-19 out of hospitals when appropriate to free up much needed space. Research has shown that patients can still get hospital-level care at home: A study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine last December found that a home hospital program reduced cost, health care use, and readmission rates compared to patients who stayed in a hospital.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)