Paying homage to a great tree

Feb. 3, 2010

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

An elm tree that served as backdrop for the promise of peace and survived a war-time wood shortage continues to grow in significance – even though it fell in a storm 200 years ago.

Over a four-day span in early March, Native Americans and Quakers, historians and a horticulturist will celebrate what that Great Elm at Shackamaxon – also known as the Penn Treaty Elm – still stands for: Fairness, peace and social justice.

This was the heritage tree under which William Penn and Lenape Chief Tamanend made a treaty of friendship in 1682. Tamanend gave Penn a wampum belt, now kept safe at the Atwater Kent Museum. The two men, representing their two societies, made a pact to live in peace and friendship.

“The treaty that took place there was one that represented the hope of mutually beneficial co-existence in peace,” said Pastor John Norwood, a Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape council member and a board member of the Penn Treaty Museum, sponsor of the Tree Celebration. (To learn more and see a full schedule of events, visit the museum’s website, http://www.penntreatymuseum.org)

William Penn’s sons broke that promise – notably through the trickery of the Walking Purchase (http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/things/4280/walking_purchase/478692) – but Norwood said his people believe it is not too late to honor the treaty. For example, school children could learn more about the alive-and-well culture of his people, he said. Some elements of that culture will be demonstrated with singing, dancing and drumming during the tree celebration.

The treaty that was signed beneath the Great Elm and other examples of American Indian governance were a source of inspiration to those who crafted American democracy, said Gregory Schaaf, director of the Center for Indigenous Arts and Culture in Santa Fe.

“When I went to college, they said our Founding Father’s ideas came from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. But if you spoke out against the leaders of Rome, they put you in the coliseum and let the lions eat you. That doesn’t sound very democratic to me,” said Schaaf, who will talk about wampum belts, peace trees and the Treaty of Friendship in a talk at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on March 4.

Schaaf, who is part Cherokee, said that chiefs who came after Tamanend became friends and advisors to people like James Madison, Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin – who wrote a book on the history of American Indian treaties. Native Americans gave John Hancock a name – Karanduwan, which means The Great Tree of Liberty, he said. The Founding Fathers learned how the Native American systems of government worked, Schaaf said. One striking difference between early American democracy and that used by the Native Americans is that Native American women had a huge role in governance. For example, women had a role in important tribal decisions, including whether or not to go to war, Schaaf said.

In 1987, Schaaf, along with Iroquois chiefs and representatives of other American Indian nations testified about these particulars before the U.S. Senate’s Select Committee of Indian Affairs. Both the Senate and the House passed a resolution recognizing that American Indian people directly influenced the U.S. Constitution, he said.

In 1983, Schaff was invited to speak at the United Nations in New York City. Beforehand, he sought the advice of elders from six different Indian Nations. They suggested the creation of a world-wide program through which people would plant one billion trees as symbols of peace. The elders were thinking about the Great Elm at Shackamaxon when they suggested the tree as a peace symbol, said Schaaf, co-founder of the Tree of Peace Society.

A tree is a great symbol for peace because “the tree symbolizes the gift from the Creator,” Schaaf said. And also because if people plant and care for trees, they receive so many gifts in return, including shade and clean air, he said. “We haven’t reached our goal yet, but over 200 million trees have been planted by many environmental and peace organizations,” he said. “I just received word from the government of India that they are committed to planting 100 million trees in their country.” For more information on peace trees, see www.treeofpeacesociety.info.

On the exact date of the 200th anniversary of the fall of the tree, March 5, Temple University’s Eva Monheim, senior horticultural lecturer, will speak about the Penn Treaty Tree and the American Elm in general at the Philadelphia Flower Show.

Penn and Tamanend reached their friendship treaty at what was then called Shackamaxon, which translates to “a place where chiefs are made,” Monheim said. This place along the Delaware, in current-day Fishtown – was where leaders from many tribes frequently met. Elm trees like to grow near water, so the Great Elm was in its element there. It is estimated to have been 155 years old in 1682, when the treaty was reached beneath it. It was surely a beautiful place, Monheim said. The huge trunk would have been covered with deeply furrowed bark. Penn and Tamanend would have looked upward at “arching branches that look like the beams in a cathedral,” Monheim said.

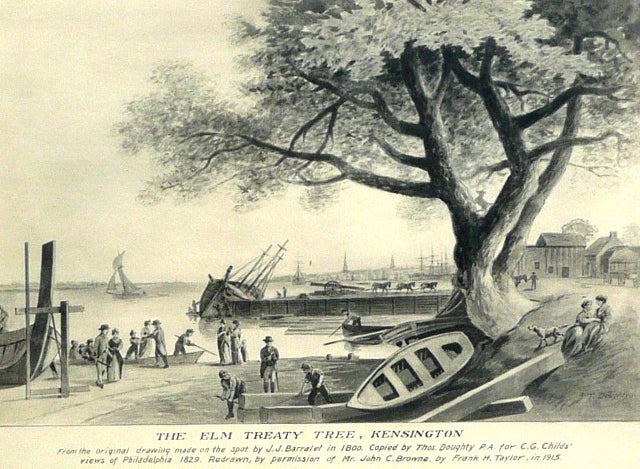

Even before the United States became an independent nation, the Great Elm appeared in art and literature. In 1771, Benjamin West painted Penn’s Treaty with the Indians at Shackamaxon. (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Treaty_of_Penn_with_Indians_by_Benjamin_West.jpg)

Many prints of this painting circulated in Europe. This is how the tree was recognized by Lt. John Graves Simcoe, who commanded the Queen’s Rangers during the Revolutionary War. The British had built a fort near the treaty tree, which put it in danger. Soldiers frequently cut down trees, both because they needed firewood and the Americans would hide behind them, and then shoot at the British soldiers.

Once Simcoe recognized the large elm as The Great Elm, Simcoe assigned guards to protect it.

The tree continued to show up in art after it fell in 1810, when it was 283 years old and had a limb that was 150 feet long.

Wood from the tree was treasured, and boxes and other items were made from it. A section was given to President Abraham Lincoln. A few items made of the wood will be on display at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

When the Great Elm fell, a shoot from it was planted in Wilkes Barre, Pa. Scions and seeds from that shoot have grown into living descendants of the Great Elm, and several can be seen in the Philadelphia region, including a great-grandchild of the Penn Treaty Elm that stands at Haverford College. In October 1982, another descendant was planted at Penn Treaty Park, a public space that preserves the site of the peace treaty, as part of the city’s Tercentenary celebration.

Gail Sweet, a board member of Penn Treaty Museum, said the falling of the tree only strengthened its symbolism. “When it fell, it hit the newspapers that this wonderful tree under which this treaty had taken place was no longer with us,” she said.

A new round of artists started using the tree in their work, perhaps most notably Edward Hicks. In his 1848 work, Peaceable Kingdom. Behind the peaceful gathering of lions and lambs, wolves and people, one can see Penn and the Native Americans talking beneath the elm. Sweet, who is director of the Burlington County Library System, has a print of Hick’s painting hanging on her office wall.

So why is it important to commemorate the falling of a tree? “It’s a good reminder of what happened 200 years ago, and a chance to look at how diverse people can come together,” Sweet said. She hopes those attending the events will learn more about Native Americans and Quakers and American history.

Norwood, the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Council member, said everyone can still learn from the tree. “The message of peace and mutual respect and sharing of resouces, of behaving as though one people, perhaps abiding under two governments, is a lesson for the entire world today,” he said. “A lot of strife that exists around the planet, between people, could be addressed by that Treaty.”

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.