Critics call water quality bill moving through Pa. legislature a back door to privatization

The bill requires some public water systems to create an asset management plan, a mandate that municipal leaders and environmental groups are questioning.

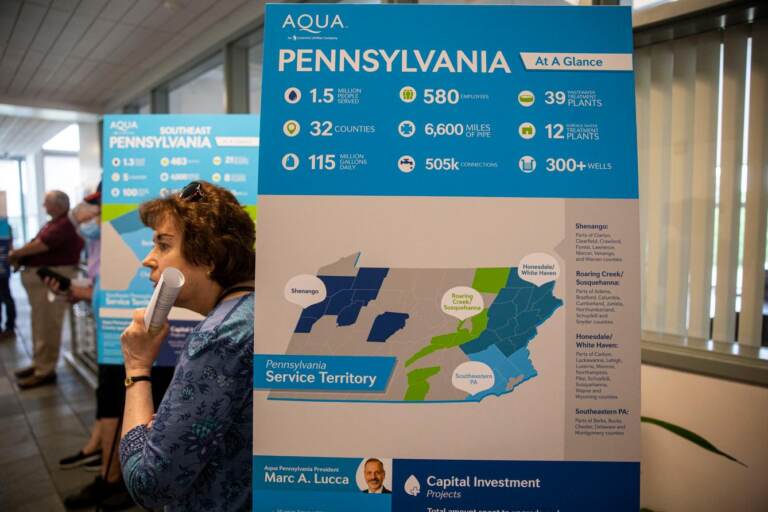

Aqua America — a supporter of the bill — is in talks to buy the Bucks County sewer system for more than $1 billion. (Tyger Williams/The Philadelphia Inquirer)

This story originally appeared on Spotlight PA.

Pennsylvania lawmakers are weighing legislation that would make it easier for private water companies to target municipal authorities for acquisition, purchases that new research shows can lead to higher bills for consumers.

The proposal — sponsored by state Sen. Pat Stefano (R., Fayette) and backed by two large, influential private utility companies — is billed by supporters as a way to increase the reliability, quality, and security of Pennsylvania’s water supplies.

It would require public water systems with more than 750 customers to develop and give to the state an asset management plan that includes a schedule for identifying and replacing infrastructure like old pipes and meters, as well as the estimated cost of such projects and the projected rate increases needed to afford them.

Municipal leaders and environmental groups are lining up against the bill, arguing it’s a solution in search of a problem. They said it would create ratepayer-funded market research for private businesses searching for their next deal under the guise of consumer protection.

“Legislators in Harrisburg come up with many, many different types of proposed regulations on our industry,” said Anthony Bellitto Jr., executive director of the North Penn Water Authority, which serves about 70,000 people in Montgomery County. “And unfortunately, most of those legislators have no idea what they’re talking about.”

The bill passed the state Senate 27-23 in June and is now awaiting further action in the state House.

The lower chamber’s Environmental Resources and Energy Committee held a hearing on the bill, known as the Water Quality Accountability Act, this week, and executives from two private water companies — Bryn Mawr-based Essential Utilities, the parent company of Aqua America, and New Jersey-based American Water Works Company — gave supportive testimony.

Combined, the two companies already serve at least 1.1 million households and businesses across the state and are eyeing expansion — for instance, Aqua America is in talks to buy the Bucks County sewer system for more than $1 billion.

At the hearing, Aqua America President Marc Lucca argued that asset management plans, as required by the bill, encourage water providers to be proactive about inspecting, repairing, and replacing infrastructure like fire hydrants and lead pipes.

“People drink our water. They drink our product,” Lucca said. “And if a provider cannot meet the most basic requirements, would you feel safe, consuming their water, or giving it to your family, your children, or grandchildren?”

Public water authorities already have to comply with the federal Safe Drinking Water Act among dozens of other state and federal laws, and release yearly reports on water quality levels. The North Penn Water Authority’s 2022 report, for instance, was clear of any violations.

In addition to requiring asset management plans, the legislation would also require water authorities to develop a cybersecurity plan and an inspection plan for valves that connect to hospitals or prevent wastewater backflows, among others.

The state Department of Environmental Protection would be in charge of reviewing and enforcing the plans, and would establish the timeline for authorities to comply with the plan.

These layers of oversight, authorities argued, could result in systems misallocating dollars. For instance, the bill singles out water meter replacement as a priority. While that sounds good on paper, Bellitto said that a broken meter isn’t a top concern, as it won’t impact a customer’s service or artificially inflate their bill.

“Let us determine what is the best way to use our limited resources,” Bellitto said. “It’s probably much better for us to replace a water main that’s had three breaks in it over the past winter than putting that money into replacing meters.”

New Jersey passed its own version of the law in 2017. Since then, local water services have had to deploy staffing and dollars in places where they aren’t needed, leaving untouched some tasks that are more urgent, said Peggy Gallos, executive director of the state’s Association of Environmental Authorities, a trade group.

Pennsylvania’s new budget allocated $320 million in federal stimulus money to water and sewer systems, and the systems also have access to billions more in aid approved in the 2021 federal infrastructure bill. That puts them in a stronger financial position.

But this sudden windfall comes after decades of underinvestment in water. The additional requirements of the proposal, Bellitto said, will continue to force authorities to choose between their own plans or those mandated by state law.

Gov. Tom Wolf, a Democrat, opposes the legislation in its current form, his spokesperson said in an email, as it would “impose significant new obligations on municipally owned water systems without a clear demonstration that the cost of those obligations are justified by the expected benefits to public health and safety.”

A path to privatization — and higher bills?

In public remarks, water executives have acknowledged a motive beyond safety for the legislation — helping to pave the way for more acquisitions.

In a February 2021 call with investors, American Water Works executive Walter Lynch was asked about “emerging legislation that would also help facilitate” mergers and acquisitions. Lynch immediately named the Water Quality Accountability Act as an example.

Forcing water authorities to take stock of their systems could be a “wake-up call for many municipalities to say ‘maybe we should talk to American Water about selling the system,’” Lynch said.

Lucca addressed concerns about privatization during this week’s state House hearing, saying it “may be a result” of the bill.

The utility industry is already a powerful political force in the General Assembly. Companies spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on lobbying and political donations every year, and a number of former legislators and staffers either work directly for, or are under contract with, the industry.

Among the most notable is former state House Speaker Mike Turzai (R., Allegheny), who is counsel for Peoples Gas, a subsidiary of Essential Utilities. As speaker, Turzai threw his support behind an ultimately unsuccessful effort by Peoples to “partner” with the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority.

Allegheny Strategy Partners, a lobbying firm in which former state Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati (R., Jefferson) is a partner, lobbies for Aqua America, according to Department of State records.

This influence, experts say, can be seen in two laws the legislature passed in the past decade. One, enacted in 2012, allows private utility companies to place surcharges on water bills outside of regular rate increases to pay for infrastructure projects.

Another law, enacted in 2016, allows for the sale of water infrastructure at market price, rather than at book value. This allows companies to inflate their purchasing price of water systems, wowing local officials with a big, one-time windfall, said Cornell University professor Mildred Warner.

The proposed water quality bill, Warner said, amounts to intimidating local governments with new requirements before private companies swoop in and offer a big check.

At first, local officials may not see much to dislike in an offer of millions of dollars to get rid of some troublesome assets.

But water services are typically a monopoly, Warner added, so it’s hard to find an accurate sale price. And the costs of maintaining the water system, whether it’s patching a leaky water main or replacing lead pipes, don’t disappear after a sale.

Instead, rate increases to fix these issues will be decided by a private company seeking profit, instead of by a public board accountable to ratepayers.

“What’s not to like?” Warner said, “Well, what’s not to like is if you’re the resident in the community, you just lost control over your water.”

In March, Warner released a study with Food and Water Watch — an environmental group that opposes water privatization — examining the 500 largest water systems in the U.S.

The study found that customers of privately owned systems paid $144 more every year on average for water than customers of publicly owned systems, and that in communities with privately owned water systems, low-income households spent 1.55% more of their income on their water bills.

The pro-industry policies already passed in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, the study added, cost ratepayers an additional $89 each year on average.

It’s unclear whether the bill will advance in the state House, as influential environmental groups have come out strongly against it.

“We are taking a much closer look across the board at bills that deal with privatization and corporate regulations because they create loopholes for companies to ignore environmental quality,” said Katie Blume, political and legislative director for the Conservation Voters of PA, an environmental advocacy group.

At least one conservative lawmaker is also skeptical. Speaking during the public hearing this week, state Rep. Daryl Metcalfe (R., Butler), who chairs the environmental committee, said that given the testimony the committee heard, he expected “additional work” on the bill.

“I’m normally against government regulating more than they already are, and I am for rolling back regulations and not imposing new ones,” Metcalfe said. “So what are we fixing?”

Spotlight PA is an independent, non-partisan newsroom powered by The Philadelphia Inquirer in partnership with PennLive/The Patriot-News, TribLIVE/Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and WITF Public Media.

Spotlight PA is an independent, non-partisan newsroom powered by The Philadelphia Inquirer in partnership with PennLive/The Patriot-News, TribLIVE/Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and WITF Public Media.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.