Pa. says 2 gas drilling companies committed environmental crimes. Here’s why corporations, not people, are usually charged

Even though corporations are made up of people who make daily decisions, environmental attorneys say it’s very difficult to target workers who may commit a crime.

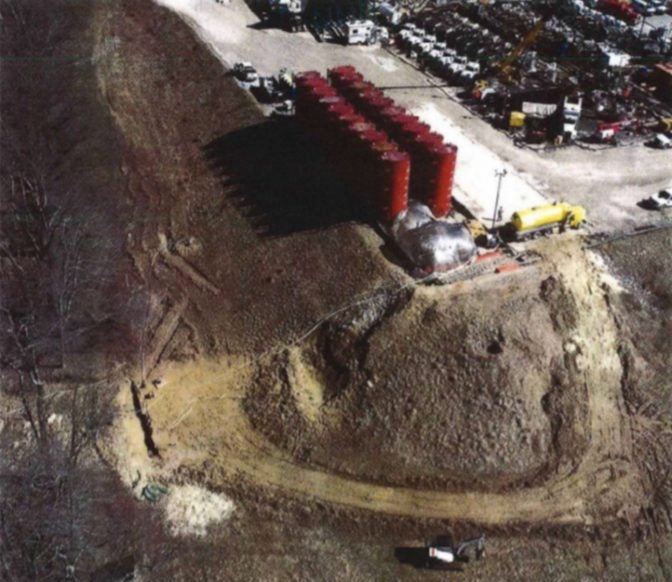

A worker operates valves at a frack water recycling plant used by Cabot Oil and Gas. (StateImpact Pennsylvania)

This article originally appeared on StateImpact Pennsylvania.

—

Following two years of investigations and evidence presented to a grand jury, the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office has filed criminal charges against two major gas drillers, Range Resources and Cabot Oil and Gas, within the past week. Missing from those charges, however, are individual names attached to the alleged criminal acts that caused water pollution.

A spokesman for the Attorney General’s office, Mark Shade, said the grand jury concluded the crimes stem from “corporate decisions.”

“When a crime is committed because of how a company does business, rather than an individual’s actions, we charge the company,” Shade wrote in an email.

Even though corporations are made up of people who make daily decisions, environmental attorneys say it’s very difficult to target workers who may commit a crime, or executives who sanction or even encourage it.

“The problem with going after individuals for environmental prosecutions is that it’s hard to pin down who is the exact person who caused it, ordered it, told about it and ignored it when they had a duty to act,” retired assistant U.S. attorney Seth Weber said. “That’s tough. Charging Cabot Oil and Gas? That’s easy. And nobody goes to jail.”

Weber spent several decades prosecuting environmental crimes in Pennsylvania, including a number of cases in which people did do jail time.

He said environmental regulations and enforcement are built around compliance — urging a company to follow the law based on violations, fines, consent decrees, and, if that doesn’t work, using civil litigation.

But Weber said all too often, companies see that process as simply the cost of doing business.

“There’s nothing like the deterrence of taking an apparently good upstanding corporate person and putting them in jail,” he said. “That will get you your compliance. You want to fine them a million dollars? They’ll reach into their pocket and give you a million dollars.”

Both Range Resources and Cabot Oil and Gas have paid multiple fines, as well as settlements to landowners, since the start of Pennsylvania’s gas rush more than 10 years ago.

Environmental attorney Steven Miano said the Attorney General’s office has a lot of discretion when it comes to who and what entity to charge.

“Sometimes it’s just politics,” said Miano, a former EPA attorney who now works in private practice. “Going after a big company, rather than a John Doe, makes a bigger splash.”

In California this week, PG&E pleaded guilty to manslaughter for the deaths of 84 people in the 2018 Camp Fire caused by the utility’s faulty equipment. While the CEO stood in court and said “guilty” to each charge, he himself is not going to jail.

“It is very unusual for a company to be charged with murder, let alone plead guilty to it,” Miano said. “Heads will roll. They just won’t roll into prison in that case.”

Range Resources was charged with negligent oversight of well sites in Washington County. Cabot was charged with violating pollution-related laws, including regulations on the discharge of industrial waste.

Range pleaded no contest — an acknowledgment that prosecutors have the evidence to prove a defendant’s guilt. But Cabot has gone in the opposite direction. In a statement released in its newsletter “Well Said Weekly,” Cabot denied responsibility for contaminating Dimock residents’ water with methane, questioning the scientific evidence and touting its positive relationship with the community.

“Cabot categorically denies assertions that the company acted with indifference toward the community where we live and operate,” the statement read. “These studies have failed to find evidence of systemic impacts to drinking water resources related to hydraulic fracturing. It is a well-known fact that methane is naturally occurring in many of the water resources of NEPA. Much of the narrative is a restatement of long discredited claims.”

The charges against Cabot relate to activities that date back to 2008 in Susquehanna County. The studies didn’t find fault with their fracking operations per se, but with the well construction that occurred before any fracking took place. And while biogenic methane, which does exist in some surface water sources in Northeast Pennsylvania, is naturally occurring, the scientific analysis conducted by DEP identified the methane that polluted water systems was thermogenic. It originated deep below the earth’s surface and was forced upward into the aquifer via Cabot’s faulty well construction. The gas found in area drinking water after Cabot’s drilling matches the gas the company had produced from its wells.

Miano said the difference between the response of Range and Cabot could come down to the people in charge.

“There are corporate cultures where they just don’t [plead guilty],” he said. “The CEO says, ‘I’ll be damned before I plead to anything.’ I’ve represented companies and individuals where you look at the case and you say, ‘We’re dead and we better plead and get the best deal we can.’ In Cabot’s case it’s more likely the CEO than anything else.”

Cabot is known for its aggressive tactics against residents who oppose the company’s practices. It took legal action against activist Vera Scroggins, and a court permanently barred her from coming within 25 to 100 feet from each of Cabot’s oil and gas sites. Cabot also had residents sign non-disparagement clauses when settling lawsuits over the water contamination, and has sued one of those residents, Ray Kemble, for $5 million for “spouting lies.” The Houston-based company’s CEO Dan Dinges made almost $14 million in 2019, according to salary.com, which cites company financial filings provided to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Miano said the AG’s office could still go after individuals if they find incriminating evidence.

When announcing the charges Attorney General Josh Shapiro said he’s just begun.

“We are in the first quarter of a long process that will result in more criminal charges,” he said.

But it’s unclear if those charges will target additional corporations or people.

Weber said it takes time and resources to target an individual with an environmental crime.

“And you’ve got to show intent,” he said. “And how do you show it? Memos, emails, texts, documents, and interviews with other employees. There aren’t a lot of those memos, emails or texts.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.