One teacher, one lesson: Common Core in Delaware up close [GALLERY]

ListenNormally, Sherry Geesaman wouldn’t be nervous.

Normally, she’d flip open a plan book or a textbook and start riffing.

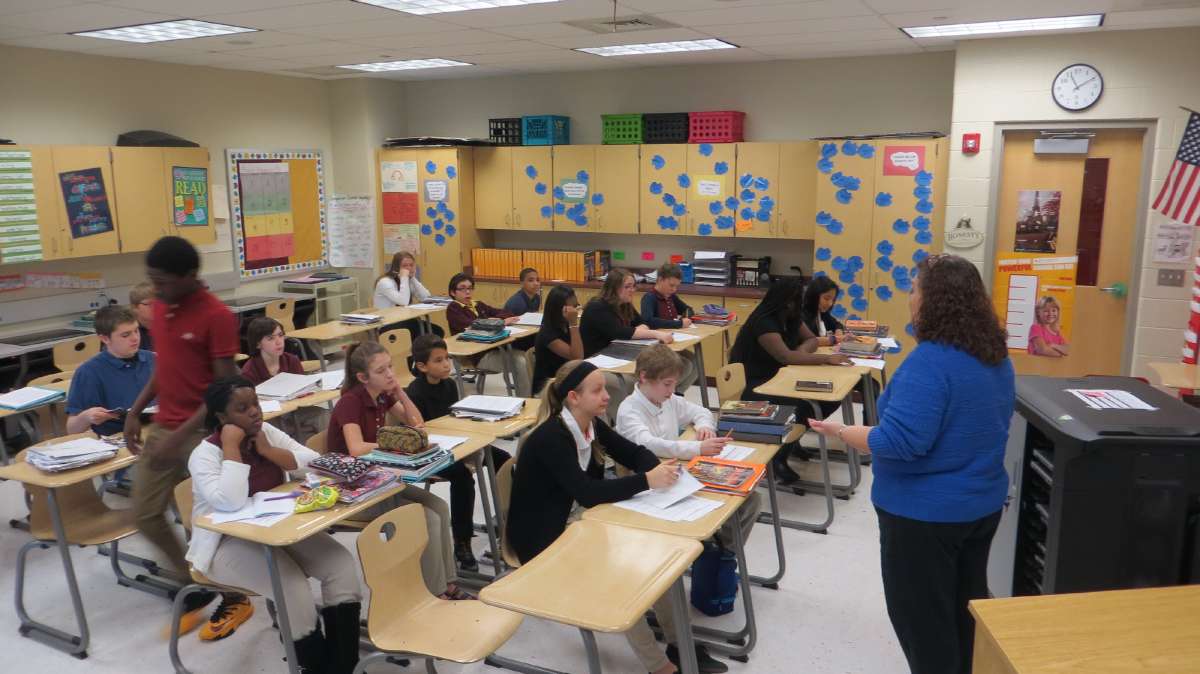

That is, after all, what veteran educators do. And Geesaman’s been teaching for 20 years, most of them as a middle school English teacher. Today, though, feels different–like starting over.

“I have taught this lesson before, but I haven’t taught it this way before,” she tells the giggly gaggle of seventh graders before her. “So it’s gonna be different. So I don’t really know what to expect. I don’t know what to expect from you guys. I don’t know how it’s gonna go. It might be a great success. It might be a big flop.”

She pauses.

“I don’t know.”

A time for doing

The lesson she’s about to teach is intently and painstakingly aligned with the Common Core State Standards, a set of educational benchmarks that outline what students should learn in each grade. Delaware officially adopted Common Core in 2010, but it’s still filtering into actual classroom instruction.

“First year you learn about them it’s like, oh here comes the new thing down the road,” says Geesaman. “They’re just pushing something else on us, so we’ll see where this goes and we’ll just sit back and wait and see until they make us do it.”

The time for doing has arrived.

This spring, Delaware students in grades 3 through 8 and grade 11 are taking Smarter Balanced, the state’s first standardized test fully aligned with Common Core principles. The results from Smarter Balanced will provide an early statistical indicator on how Delaware students are taking to the new standards. For teachers, the impending test has forced many to integrate Common Core more deeply and completely than in past years. And it means many, like Geesaman, are getting up in front of their classes and trying something new.

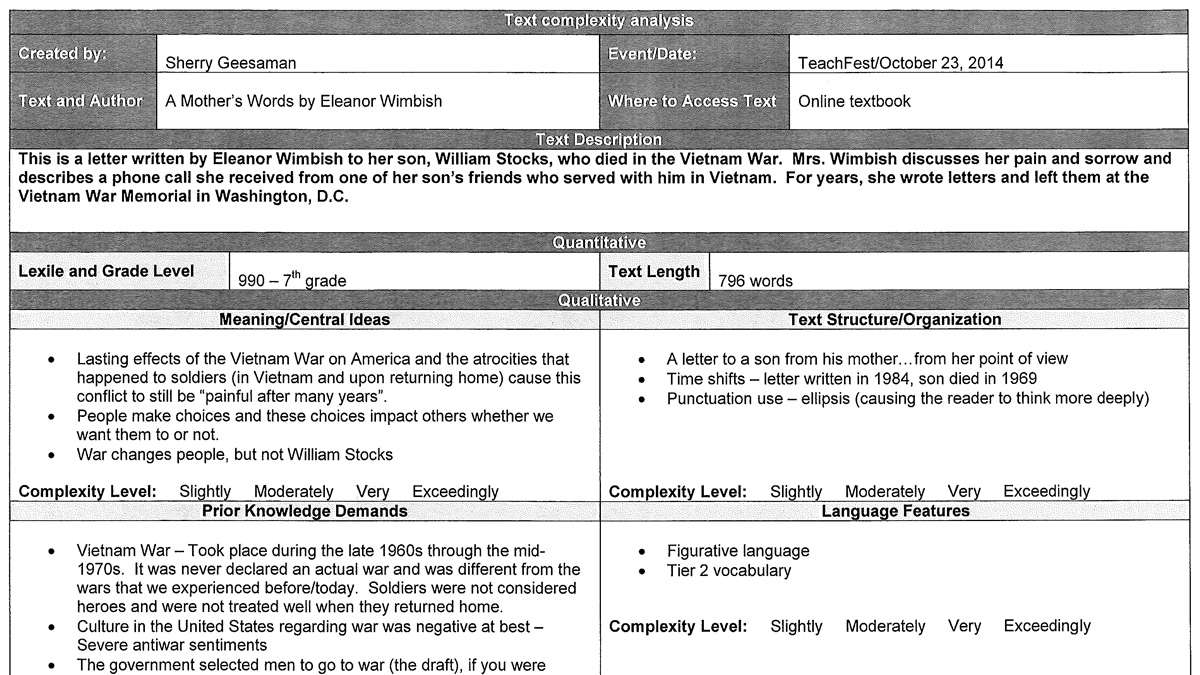

The Dream Team

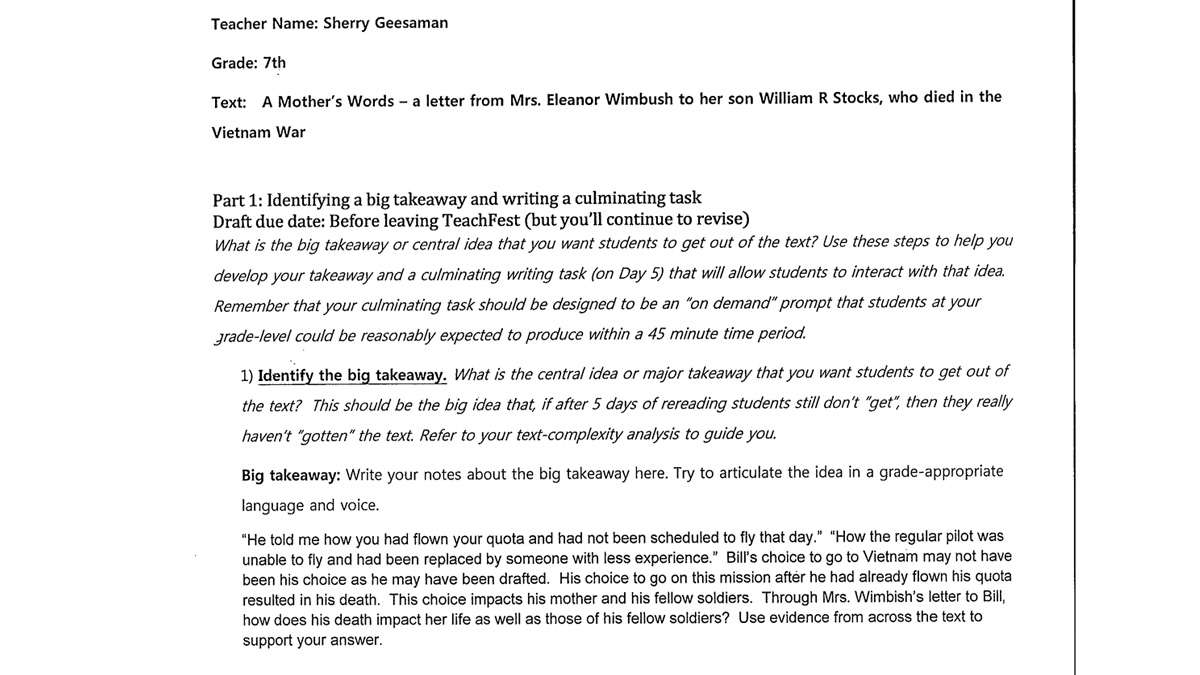

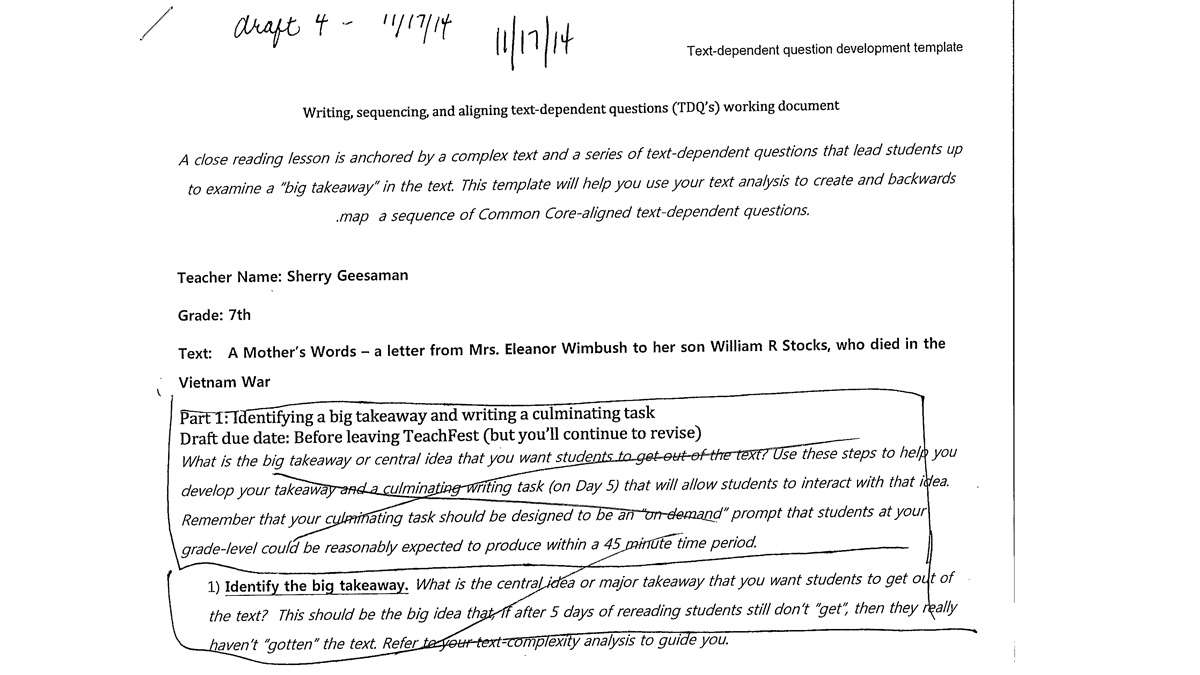

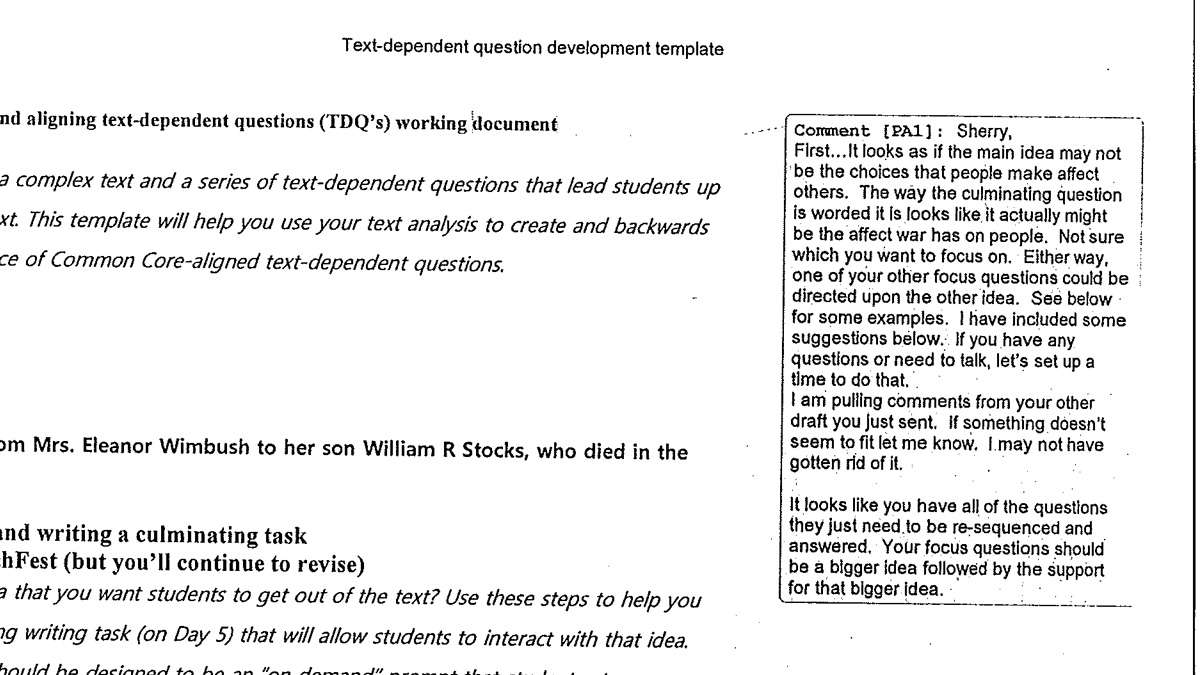

Last fall, Geesaman joined the second cohort of Delaware’s Dream Team. Together with about 40 teachers from around the state, Geesaman was asked to come up with an intensely detailed lesson plan that corresponded to some aspect of the Common Core. She spent about five months mapping that lesson, complete with takeaway questions for each of the lesson’s five days and daily schedules that detailed exactly how many minutes each portion of the lesson should take. During that time she corresponded with a coach provided by LearnZillion, a for-profit contractor that helps teachers devise Common Core lesson plans and share them with one another on an internet platform. She and the coach swapped draft after draft–at least five formal ones–until the lesson was deemed ready. Then, she prepared to teach it.

The Dream Team is just one of many ways Delaware’s Department of Education wants to implement or “roll out” Common Core. Sometimes that roll out takes the form of formal presentations at professional development meetings. Other times it looks more like a school buying new textbooks that are labeled “Common Core aligned” and telling teachers to make do. The Dream Team model is harder to scale than either of those two, but it’s far more intentional–and hopefully more meaningful for those that participate.

So far, about 80 Delaware teachers have been selected for the Dream Team. In addition to creating their lesson plans, the teachers are expected to share what they’ve created with other teachers. Those teachers share with still more teachers, and the lessons filter outward in concentric circles. This May, for example, Dream Team alum will sit down with other educators from around the state at an event hosted by LearnZillion to talk about implementing Common Core in the classroom.

Many of the Dream Team teachers are unabashed Common Core cheerleaders. In fact, LearnZillion encourages its dream teamers to rally support for the core by chatting up other teachers. The company even screens inspirational video clips where educators extol the virtues of these new, tougher standards.

“It’s what we have to do”

Sherry Geesaman, however, is no cheerleader.

She likes Common Core. She thinks the higher standards will help her seventh graders at Milford Central Academy in central Delaware become better critical thinkers and eventually more desirable job applicants.

But after two decades in the classroom, Geesaman has seen enough educational trends come and go to think this one is a silver bullet.

“There’s always gonna be standards,” she says. “We always have to teach by standards. It’s just [that] what they’re called changes.” Sometimes, Geesaman says, the changes can feel forced. “But in the end it’s what we have to do,” she explains. “So we do it.”

Geesaman’s ho-hum pragmatism may feel at odds with kinetic public debate around Common Core, but it reflects how a lot of teachers approach the standards. While teacher affinity for the Common Core standards has dropped steeply in recent years, roughly half still support them according to two recent polls. One of those polls, conducted by Gallup, suggests that educators overwhelmingly support the ideas behind Common Core. And even among those who feel negatively about the standards, most are “resigned to” their presence.

In other words, there are a lot more teachers like Sherry Geesaman than the larger Common Core narrative would lead you to believe.

“When you’ve taught for 20 years you’ve seen the changes go through and there’s no sense getting upset about it because they’re here,” says Geesaman. “You just have to go with the flow. I mean there’s plenty of things to get upset about in education. Teaching kids shouldn’t be one of them.”

Geesaman’s reasons for joining the Dream Team are similarly straightforward. If her student are expected to know something new, she wants to make sure she can teach it.

One letter, five days

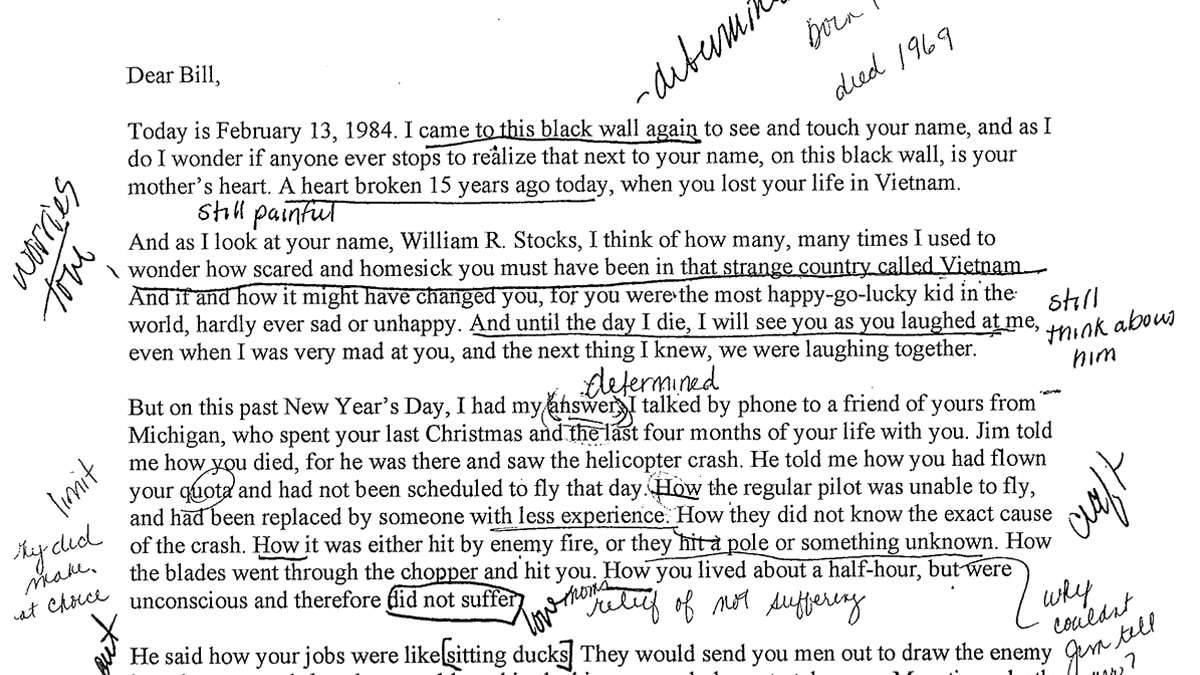

For her Dream Team lesson, Geesaman picked a letter written by the mother of a soldier who died in Vietnam. The letter is just under 800 words long. For the past four years, she’s spent part of one class teaching this text.

“We would introduce it to kids, but we may not go as in depth,” says Geesaman. “This is a five-day lesson plan that I’ve developed around this letter.”

That’s right–five days, 800 words.

One day the students will look at figurative language in the text. One day they’ll dissect sentence structure. By the time the lesson ends, they’ll have picked over every sentence and syllable.

“The new buzzword now [is] close reading,” Geesaman says. “Kids actually read and re-read and re-read more than once. You know they’re gonna read this letter probably–over the days–six, seven, eight times to actually interact more deeply with the letter rather than just reading it and saying oh yeah that was a nice letter.”

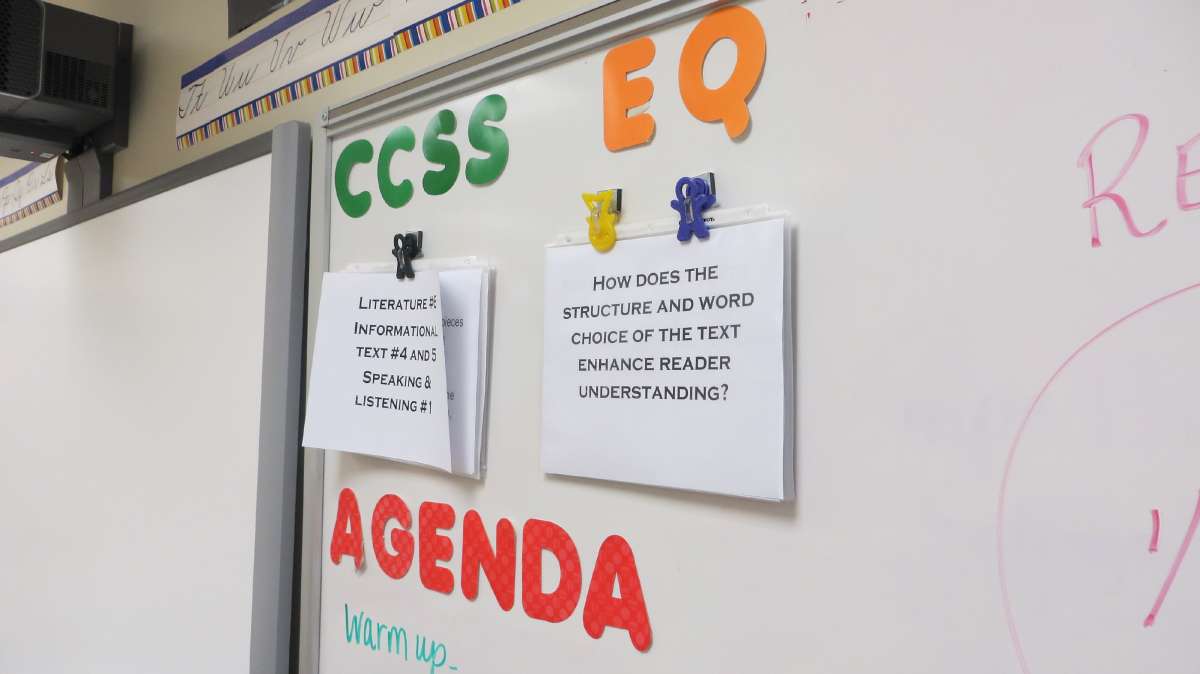

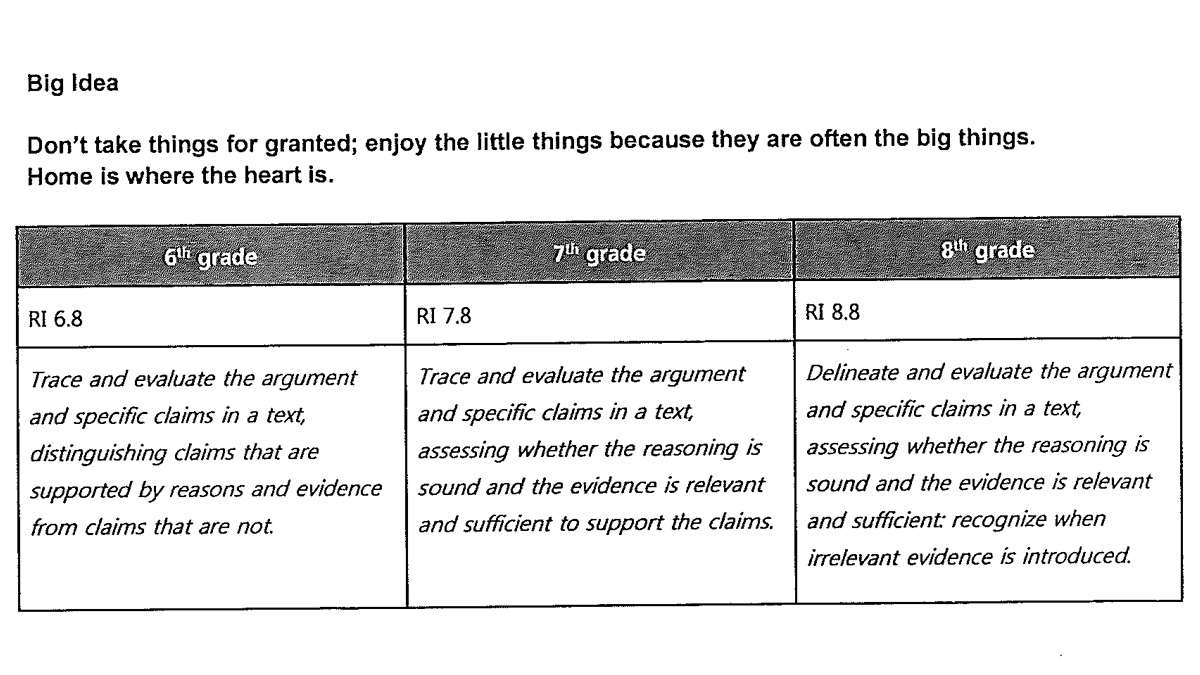

The Common Core State Standards cover every grade and and all sorts of subject matter. In 7th-grade English alone, there are standards for speaking and listening, reading literature, writing, and language usage.

The first day

Today’s lesson focuses on reading informational text, or nonfiction. Within that focus, Geesaman wants the students to master one of three key ideas, namely the ability to “cite several pieces of textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly.”

Before she can get there, though, Geesaman begins her carefully choreographed class period with a warm-up question.

“Would you rather have someone for a short time rather than to never have had them at all,” Geesaman asks the class.

It’s just the type of provocative question middle schoolers eat up, and soon a debate emerges. One student says you should enjoy love ones while you can. Another says the pain of losing someone close is too much to bear.

After a few minutes of chatter, Geesaman pivots to the letter. “So we’re going to do what we’ve talked about before. We’re going to do this close read,” Geesaman announces.

First time through, the students read the letter aloud. Once that finishes, Geesaman tells her charges to read the letter again to themselves and scribble notes in the margin.

“I want you to re-read the letter to yourself closely, carefully, word-by-word, line-by-line,” Geesaman says.

The Common Core learning begins

Here, the Common Core learning begins. Over the next half hour, the students raise questions inspired by tidbits of text. When the youngsters stray, Geesaman nudges them back toward Common Core principles.

“Use the text-based evidence,” she says as they discuss how the culture of war changes people’s attitudes. “Write from the text.”

Again and again she hammers at the same phrases and concepts.

Text-based evidence.

Close reading.

In the letter, the mother talks about meeting a soldier who served with her son, and hearing from him about how Vietnam gave men a “mean streak.” Geesaman and her students dissect that phrase and what it means. They talk about what war does to people, and as they do Geesaman hews closely to the Common Core and its principles.

“What do you see in these two paragraphs,” she asks. “And use the text-based evidence. Write from the text. What do you see in there that reflects the culture or the climate of how it was over in Vietnam?”

At one point, Geesaman asks the students to cite direct textual evidence in the letter that proves the mother loves her deceased son. It is an absurd question on its face. But given the day’s objectives, the simplicity of the question matters less than how it is answered.

“The obvious answer is that she write letters to her son, which shows that she loves him,” Geesaman says aloud. “That’s obvious. But you have to go back into the text and pull information from the text in the letter that shows how she loves him.”

Improvising

At times, her directives serve as guidance. At other junctures, they feel regimented and forced. Still other times, they melt away as Geesaman follows some improvised line of questioning elicited by a student response.

Take, for example, the tender moment when Geesaman deviates from her script and talks about the time she kept a journal to deal with a difficult time in her son’s life.

“I needed somebody to talk to, so I wrote,” Geesaman tells the class. Then in a moment of exaggerated enlightenment she continues, “Ohhhh so do you think this is helping Mrs. Wimbish cope with her son’s death?”

The students answer in a chorus: “Yeah, yeah, yeah!”

A small voice from the back of the class interrupts, “My counselor tells me to do that.”

Another pipes up, “It’s kind of like your own therapy.”

This undeniably awesome and vulnerable moment does not correspond to a Common Core standard. It does, however, seem inspired by the intense energy Geesaman and the students are pouring into this one piece of text. And as the class period winds down, Geesaman seems satisfied with how her students responded to her well-planned experiment.

“I thought their answers were, like, spot on,” she says afterwards. “Several times I was like, they’re doing it, they’re doing it.”

The last day

Fast forward four class periods, and Geesaman’s lesson plan is finally winding down.

Her final class feels like her first. She’s still hounding the students about “text-based evidence” and her students are still surprisingly receptive to the prodding.

Geesaman considers the lesson a rousing success.

“It so works,” she says with a triumphant smile.

Geesaman is still sold on Common Core, perhaps with a bit more gusto than when she began this journey. She sees her students growing into more complete scholars, and believes deep text analysis breeds good intellectual instincts.

“We need to be able to go deeper and ask questions and wonder why things happen,” Geesaman says. “And if we don’t have the tools to do that then we’re developing a nation of non-thinkers.”

“Not for the weak”

Those tools, however, can themselves feel scripted. Perhaps this is to be expected. Big instructional change like Common Core doesn’t happen by osmosis. They happen when people think consciously about the change and struggle intently to enact it.

Indeed, the biggest shift in Sherry Geesaman’s 7th grade English class probably isn’t the substance of what she’s teaching or how she’s teaching it. Instead its the standards themselves–just how present them seem to be.

“I’ve always taught to standards,” Geesaman says. “The difference now is that I’m putting standards on the board. The kids see the standards. I mention the standards to the kids.”

Outside Geesaman’s classroom door, the debate rages on about whether Common Core works. But inside, there is no debate. Geesaman knows the standards. Her students know the standards. They are impossible to ignore.

“Teaching is not a close your door and do what you wanna do in your room [thing] anymore,” Geesaman says. “Teaching is…”

She take a long and deliberate pause, searching for the word.

“It’s not for the weak.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.