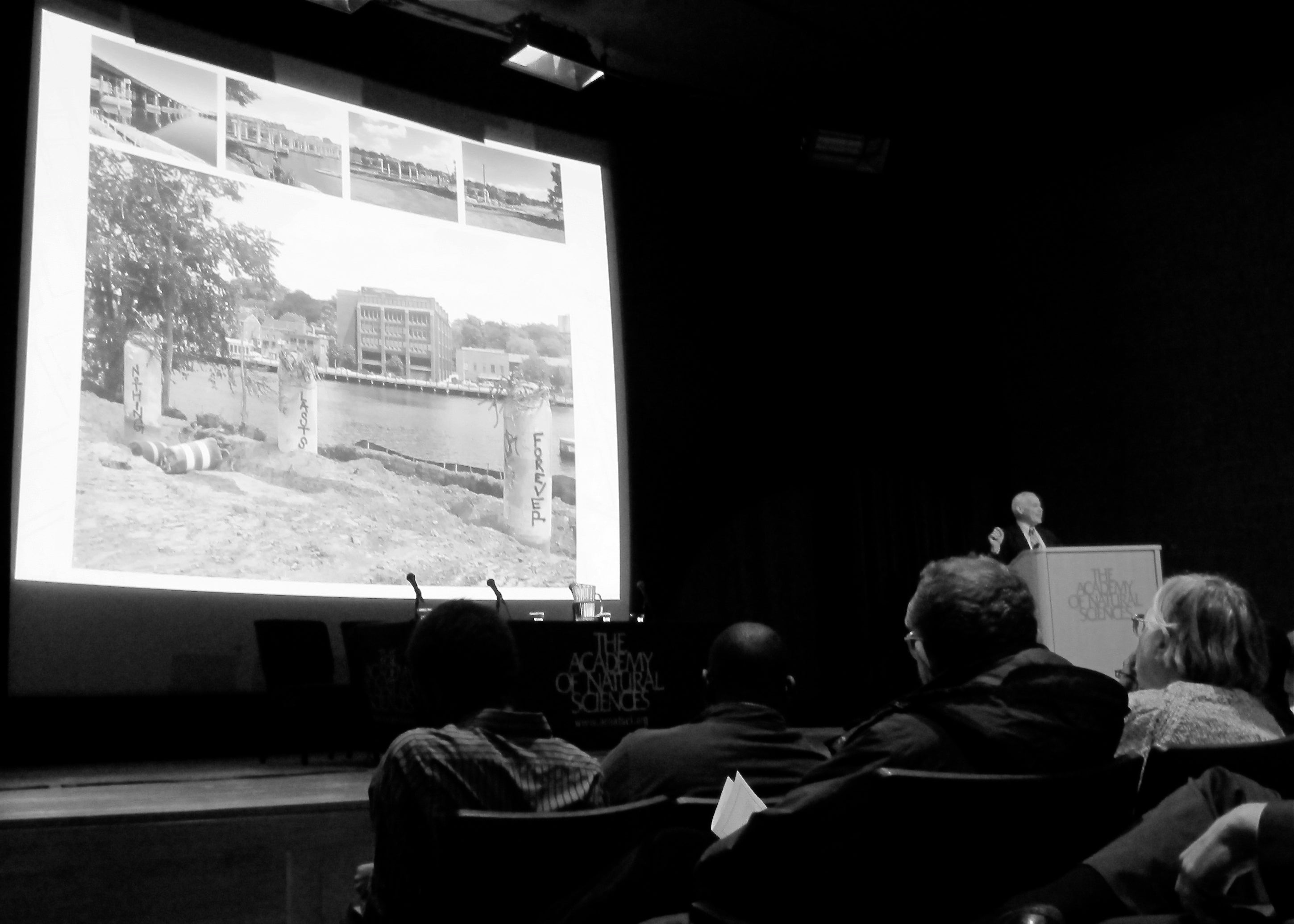

On Beyond I-95: Nothing lasts forever

The panel at Thursday night’s forum on urban highway removal may have been preaching to the converted, but the fact that Philadelphia is starting to have a public conversation about altering a portion of I-95 is a step in the right direction.

We’re bringing up highway removal again because I-95, our very own waterfront highway, will need to be rebuilt due to “structural obsolescence” over the coming decades. But what if the portion of I-95 between the Benjamin Franklin and Walt Whitman bridges was not rebuilt? Could we cap part of it? Shrink it? Erase it? Right now those alternatives are not on the table with PennDOT and the Nutter Administration sees them as a nonstarter. Still the question remains: Why would we recreate mid-20th century infrastructure to serve 21st century Philadelphia?

To help contextualize the conversation in Philly, Diana Lind from Next American City invited planners and highway removal experts from Minneapolis, Providence, and New York to share their experiences with an eye toward the challenges and opportunities presented by Philly’s stretch of I-95. Andrew Stober from the Mayor’s Office of Transportation and Utilities was a late addition to the program, and the forum was more interesting with his participation. [Head over to Next American City for video of the event.]

Here are a few things from last week’s conversation that I’m still chewing on:

- Analyze this: We know roughly how many vehicles travel on I-95 between the bridges every day. (Diana Lind said about 90,000 while Andrew Stober says it’s more like 140,000.) But we don’t know how any alteration or removal strategy will affect the city. As Inga Saffron mentioned in her post about the forum, a robust cost-benefit analysis of different scenarios for I-95 should be undertaken asap. Without better data for different scenarios, there is no real argument to be made for any solution. So much as I think highway removal advocates need a stronger case, PennDOT and the Nutter administration need to prove that the best option is to rebuild the highway as-is. And if the city won’t study the alternatives, an someone else should.

- Delaware waterfront destinations vs obstacles: Andrew Stober said he think’s the waterfront’s problem is that it lacks destinations, not because I-95 is in the way. The revitalization of the waterfront is off to a positive start, and its transformation is going to be a generational process. I think the city’s planners acknowledge that new life on the waterfront will happen despite I-95’s oppressive presence, but it might make the process even slower. Will the Connector Streets, meant to improve the dark and uninviting underpasses beneath I-95, actually be enough? I’m not convinced.

- Show me the money: The price tag for altering I-95 is often cited as something the city and state can’t justify given all of Philadelphia’s competing transportation needs. To Stober the days of large-scale federal transportation funding programs are long gone. When asked how anyone would justify the millions and millions of dollars to even rebuild I-95, Andrew Stober replied, “The reality that I see going forward is, we probably won’t. I don’t see the political will to maintain the infrastructure that we have.” Scary. But won’t the money have to come from somewhere. And if it doesn’t, then what? Partial collapse? (Or perhaps there’s a new viaduct park waiting to be born of I-95’s decrepit remains?)

- Too soon vs too late: Peter Park, who oversaw the highway removal project in Minneapolis, reminded the crowd that there are two phases for planning any DOT project: “too soon to tell” and “too late to change.” We’re in the former, but that window of opportunity is rapidly shrinking and these projects take a long time to plan. If there’s really no money to be spent on I-95 in the foreseeable future, we’re waiting for an accident. If I-95 has to be closed because of dangerous conditions, we’ll have no time to plan. So the time to plan is now.

- Nothing lasts forever or history repeating: Philadelphia’s Chinese Wall was torn down in the 1950s. And during the 1970s Philadelphians fought off a Crosstown Expressway that would have razed South Street. Philadelphia has removed hulking and divisive infrastructure before and regular folks changed the course of large-scale highway plans even though the wheels were already in motion. I appreciate the pragmatic talk, and can’t wait to hang some real data on the question of altering I-95s future through our city. But highway removal is also question of public and political vision and will. As with so many things, a different future is possible if we’re willing to work for it.

Want more?:

- Kicking around city’s future options for I-95 [PlanPhilly/Philadelphia Neighborhoods, February 24, 2012]

- Where’s the Data? [Changing Skyline, Inquirer, February 24, 2012]

- Could we actually get rid of I-95 downtown? [The Naked City, City Paper, February 24, 2012]

- Urban Highways as Land Banks [Car Free Baltimore, February 27, 2012]

- Knock down I-95? [Heard in the Hall, Inquirer, February 23, 2012]

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.