Officials change COVID testing advice, bewildering experts

The new guidance was posted earlier this week on the website of a federal agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

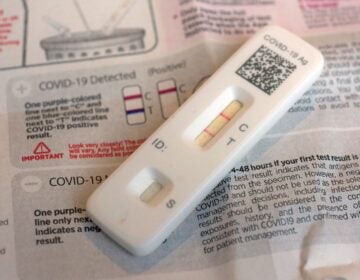

An antibody test for the coronavirus can indicate whether someone has been infected, but it's just one measure of immunity, researchers say. How robust that immunity is and how long it lasts are still open questions. (Simon Dawson/AP Photo)

Updated: 5:36 p.m.

U.S. health officials sparked criticism and confusion after posting guidelines on coronavirus testing from the White House task force that run counter to what scientists say is necessary to control the pandemic.

The new guidance says it’s not necessary for people who don’t feel sick but have been in close contact with infected people to get tested. It was posted earlier this week on the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC previously had advised local health departments to test people who have been within 6 feet of an infected person for more than 15 minutes. But on Monday a CDC testing overview page was changed to say that testing is no longer recommended for symptom-less people who were in close contact situations.

There was a caveat, however. Testing may be recommended for those with health problems that make them more likely to suffer severe illness, or if their doctor or local state officials advise they get tested.

Across the country, public health experts called the change bizarre. They noted that testing contacts of infected people is a core element of public health efforts to keep outbreaks in check, and that a large percentage of infected people — the CDC has said as many as 40% — exhibit no symptoms.

“The recommendation not to test asymptomatic people who likely have been exposed is not in accord with the science,” said John Auerbach, president of Trust for America’s Health, a nonprofit that works to improve U.S. preparedness against disease.

“We are seeking clarification from CDC about its recent guidance around testing,” said a spokesman for Michigan’s health department.

Some — including at least two state governors — said it was another sign of a dysfunctional federal response to the pandemic.

“This is like a public health version of Vietnam,” said Brian Castrucci, president and CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation, which works to strengthen the public health system.

CDC officials referred all media questions to the agency’s parent organization, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in Washington, D.C. That suggests that HHS ordered the change, not CDC, said Jennifer Nuzzo, a Johns Hopkins University public health researcher.

After Twitter lit up with head-scratching and alarm about the change, HHS officials sent an email Wednesday saying the guidance was revised “to reflect current evidence and the best public health interventions,” but did not detail what the new evidence was.

The decision came out of meetings of the White House coronavirus task force, HHS officials said.

In a call with reporters, Dr. Brett Giroir, the HHS assistant secretary for health, said the guidance language came from the CDC. But he also said many people were involved in “lots of editing, lots of input.” He said federal officials achieved consensus but it was difficult to attribute the final language to any one source.

Ultimately, restricting testing could be self-defeating, because it could skew the numbers and create a perception that rates of infection are higher. Testing people who appear to be healthy would tend to lower the overall rate of positive results, while narrowing testing to people who are sick would raise the overall positive rate, Auerbach said.

Why HHS would order such a change quickly became a matter of speculation. Dr. Carlos del Rio, an infectious diseases specialist at Emory University, suggested in a tweet that there are two possible explanations.

One is that it may be driven by testing supply issues that in many parts of the country have caused widely reported delays in results of a week or more, he suggested.

In the HHS email, agency officials said that is not the reason, and argued that testing capacity is plentiful.

But Dr. Mysheika Roberts, health commissioner for the city of Columbus, Ohio, said testing in her city last month had to be curtailed because of a shortage of reagents used in lab procedures.

“I feel so strongly that we should test asymptomatic people when the capacity allows you to,” she said. “And when we were testing asymptomatic people here in Columbus, we were picking up a large number of individuals.”

Another possible explanation for the change is that President Donald Trump simply wants to see case counts drop, and discouraging more people from getting tested is one way to do it, del Rio said in his tweet.

Giroir said the change in guidance was passed by consensus by the White House task force without input from Trump or Vice President Mike Pence. “There was no weight on the scales by the president or the vice president” or HHS Secretary Alex Azar, Giroir said.

Dr. Tom Frieden, who was head of the CDC during the Obama administration, said the move follows another recent change: to no longer recommend quarantine for travelers coming from areas where infections are more common.

“Both changes are highly problematic” and need to be better explained, said Frieden, who now is president of Resolve to Save Lives, a nonprofit program that works to prevent epidemics.

Frieden said he, too, believes HHS forced CDC to post the changes. He called it “a sad day” because “CDC is being told what to write on their website.”

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, both Democrats, criticized the new recommendations.

Inslee said on Twitter that the changes likely will cause thousands of infections in his state to go unrecognized, and allow the virus to spread even more. Cuomo said his state would not be following the guidance.

“Why would you reverse yourself on the quarantine order? Because they don’t want publicity that there is a COVID problem. Because the president’s politics are, ‘COVID isn’t a problem We’re past COVID. It’s all about the economy,’” Cuomo told reporters on a conference call.

“What possible rationale is there to say, ’You’re in close contact with a COVID-positive person. And you don’t need a test?’” Cuomo said.

The principal investigator of California’s contact tracing program, Dr. George Rutherford of University of California, San Francisco, agreed.

“I hesitated to say public health malpractice,” Rutherford said. “In order to control this, especially in the context of contact tracing, you absolutely have to test people without any symptoms.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)