No. 6: a crucial ballot question

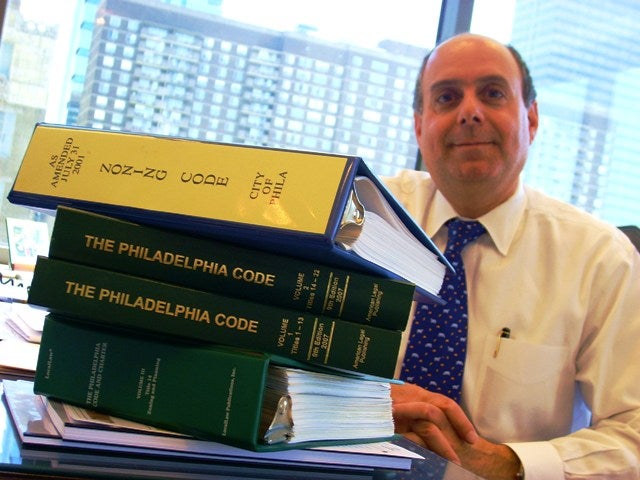

Philadelphia’s arcane zoning code keeps attorneys like Peter Kelson (photo, above) of Blank Rome in business. But even he is now pushing for its reform.

By Matt Blanchard

For PlanPhilly

On May 15, voters struck a major blow for smart planning in Philadelphia, as well as for urban reinvestment and community-friendly design, by remembering three little words: Yes on six.

The ballot for Tuesday’s primary was a busy one, with five mayoral candidates and eight referendum questions vying for voter attention.

But no ballot question is likely to shape the city’s physical future more than Question 6. It calls for the total overhaul of Philadelphia’s 1962 Zoning Code, an often mind-boggling mass of municipal regulations that governs land development in our city. Placed on the ballot by unanimous vote of City Council, Question 6 would remake both the code itself and the maps with which it’s applied.

The problems with our zoning code are well known: The 624-page document has been layered with thousands of amendments over the last 45 years. Like some ancient gospel, its requirements are often inconsistent and open to interpretation by city zoning officers and the Zoning Hearing Board, and they don’t always agree.

That uncertainty leaves developers risking millions on projects with no certain outcome. It rewards political connections and pay-to-play deal making. And it forces community groups to wage guerilla warfare to secure basic streetscape amenities that, in other cities, are required by the zoning code and come without a fight.

“We’ve really got a code that has not been fundamentally rethought since it was cooked up,” says Planning Commission director Janice Woodcock, “and that probably isn’t true of any other major city.”

The Upside

While these complaints are driving the reform movement, less has been said about the possibilities for positive change should question six pass.

A yes on six means Philadelphia will not only simplify the code itself, but will, in the coming years, create a comprehensive, community-driven master plan for development in every neighborhood of the city.

On design matters, a yes on six could mean the enactment of progressive zoning measures to encourage green building technology and transit-oriented development.

And by making Philadelphia more attractive to outside developers, a yes on six could help draw new investment to city neighborhoods, raise tax revenue, create jobs and retain our dwindling middle class. Nine other major American cities, from Pittsburgh to San Diego, have rewritten their zoning codes since 1999, seeking the same rewards.

That’s why all six mayoral candidates have come out in favor of zoning reform. At a recent mayoral forum, former councilman Michael Nutter expressed the common sentiment.

“I ask everyone to support the zoning reform ballot question,” Nutter said. “Reforming the zoning code… is the start of the renaissance of Philadelphia.”

The Downside?

But will the public support it? And do we lose anything by streamlining the zoning code? Will it bring peace to the perennial war between developers and neighborhoods? Or will it merely shift the advantage to one side? With developments being reviewed on a faster track, could developers take the upper hand and community groups lose their power to object?

For 11 years, Julia Chapman fought the zoning wars for the neighborhood side as chief of staff to former councilman Nutter. She averaged 15 to 20 zoning hearings per month, and estimates that negotiating development matters consumed a full 50 percent of her staff’s time.

Community groups, she said, are so used to a dysfunctional zoning code that some view legal fights as their best defense. They get nervous on those rare occasions when a major project doesn’t need a variance, because the permit is granted over-the-counter with no zoning hearing at which to raise a ruckus.

Chapman sees anxiety about zoning reform as understandable but misplaced.

“There’s a concern in the community that changes to the zoning code will result in more over-the-counter permits,” she said. “But if we had a code that ensured a lot of the things neighborhoods try to get in the form of provisos, like landscaping or historic design standards, we could spend our time doing something else.”

A proper code, Chapman said, would contain design standards, incentives for transit-oriented development, and protections for community open space. “All these things we spend our time arguing about would be in the code,” she said.

On the development side sit zoning attorneys like Peter Kelsen, a partner at Blank Rome with more than two decades in the zoning game.

To some extent, Kelsen’s livelihood relies on his special understanding of a zoning code that others find unfathomable. Indeed, zoning lawyers may be the only class of people who profit from a confusing code. Yet Kelsen is foremost among those calling for reform.

“Every developer I represent – the big guys down from New York or the mom-and-pop operation that wants to build a grocery – the one thing they all want is certainty,” he said.

Kelsen believes a modern zoning code will provide that certainty, attracting more national developers and more high-quality development.

“If this passes in Philadelphia, you’re going to start to see, in three to five years, we could double and triple the quality of the what we have now,” he said.

Developer Bob Rosenthal agrees. Working for Westrum, Rosenthal led the acquisition and rezoning of 2,500 properties for the new Brewerytown and Packer Park developments. He says developers don’t expect to achieve the upper hand in local politics. They will willingly adjust to new restrictions, provided they gain predictability.

“There’ll always be local politics of some kind, and we’ll always have to respond to that,” Rosenthal said. “As a developer, if the city tells us it’s going to take 36 months to go through the approval process, that’s fine. But we want to know what that process is going to look like.”

A Code of its Time

The Philadelphia Zoning Code was written in 1958, approved in 1962, and to some extent still lives in that distant era. Critics note that it provides for such uses as saw mill, soda fountain, milliner’s shop and tannery, yet outpatient medical clinics are nowhere mentioned. The term “carbon paper” is mentioned, but never “computer.” And it is said that every new Starbucks must meet the requirements for the designation “nightclub,” because after all, they do serve beverages and play music.

Yet the code was cutting edge for the late 1950s. The industrial era was drawing to a close, and planners sought to disentangle the tight 19th century mix of residential and factory properties. As housing development sprawled into agricultural Northeast Philadelphia, they sought to put upon that region the stamp of clean-living suburbia.

This led to the most notorious paradox of the zoning code: The ubiquitous and celebrated Philadelphia row house is, strictly speaking, not allowed in Philadelphia. A report by the Building Industry Association provides the details:

In 1962, the new Zoning Code made most of residential Philadelphia a “non-conforming use.” The code intentionally made it impossible to build a standard Philadelphia row house in order to reduce density in the city and work towards a more suburban pattern of growth. Although the average city lot size is 2,400 sq ft., 10,000 square feet was set as the minimum lot size for houses in R1 Single Family Zoning Districts. Also, setback requirements of 35 feet from the street were adopted for new construction in single-family districts.

So, if your row house burns down, you’ll need a zoning variance and perhaps an attorney to rebuild it, explains Karen Black, author of the BIA report. You might also need a second variance to reach its original height, unless, of course, you happen to live in Janie Blackwell’s West Philadelphia council district, where a special zoning overlay restores full rights to the row home. Go figure.

The 1962 code also assumed a city population of 2 million, and its planners predicted continued growth.

As we know, the city didn’t grow. Instead it lost jobs and shrank by half a million.

The zoning code itself, however, showed impressive growth. City Council added new amendments and regulations until there were 55 different zoning categories and over 40 special overlay districts.

The code lists 31 separate categories for residential alone (Pittsburgh has just five). The categories have names like R1, R2 on up to R20, each stipulating different minimum lot sizes, building set backs, yard requirements and height limits. Then there are oddballs like R10B and RC5, invented to accommodate specific developments that never came to pass.

Mostly harmless, this patchwork of zoning designations means that what developers can build changes block-by-block, adding to their frustration and design expense. It’s one more reason not to build in the city.

As Black writes in the BIA report: “Pittsburgh has 5. Baltimore has 12 residential zoning districts. So why does Philadelphia need 31?”

A code for our time

Reform advocates argue that a re-written code will not only be fair and predictable, it will add progressive planning tools to the city’s toolbox.

Pittsburgh’s rezoning effort, “Map Pittsburgh,” has focused on encouraging increased density by ditching its 1950s-era requirement that homes sit in the center of large lots. This is especially the case around mass transit stations, where the new code allows for high-density, mixed use development. The strategy will create new urban nodes, and is meant to add new riders to the transit system rather than the highways.

Seattle achieves the same goal with an “Urban Villages” program. It calls for affordable housing, pedestrian-oriented commercial areas, and higher density development around mass transit stations, as well as bike routes to other villages.

With new transit-oriented development incentives, Philadelphia could capitalize on the extensive SEPTA system it’s already got, and perhaps add more fare-paying riders.

Secondly, a modern zoning code can reward developers who build with energy-saving, environmentally-friendly technologies. In Arlington, Virginia, a developer who meets the national LEED standards of green design can win a zoning bonus of three additional floors. That allows the cost of green design to be offset by income from the extra rentable space. Arlington and its air quality come out on top.

Third, a modern code would speed the approval process and reduce bureaucracy. Right now, 35 percent of all development proposals must go before the Zoning Board of Adjustment, generating a morass of paperwork and legal fees. Even far larger cities like New York actually require fewer zoning appeals thanks to modern, clearly-written codes. The Big Apple offers another innovation: Simple line drawings of what can be built in each zone obviate the need to parse pages of legalese.

Finally, rather than allow politicians to tweak neighborhood zoning at will, a modern code can be developed by the neighborhood itself. Boston’s code is the product of intense citizen involvement. Overhauled in stages since 1988, the code gives each neighborhood its own, tailor-made zoning district. The process takes an extraordinary four years per neighborhood, with weekly workshops in the community.

Philadelphia planners say they’ll pursue a similar community-driven strategy called “design review,” asking neighborhoods to help set guidelines for how new buildings should look, and how they should relate to the street.

“The quality of design is something that affects the city for a long time,” the planning commission’s Woodcock said. “If design review is done right, it’s a way for a neighborhood to say exactly what they want to see happen.”

The process of reform

The yes vote on Question 6 triggers the following chain of events.

First comes the appointment of a 31-member Zoning Reform Commission. All zoning consists of two elements, the code of regulations and the maps that show where those regulations apply. The Commission’s job is to tackle the first half, proposing specific changes to the zoning code.

The commission will be chaired by city planning head Woodcock, an architect and former head of Philadelphia’s AIA chapter.

Its membership draws from government, business and community groups, including 10 citizens with zoning experience (half appointed by council and half by the mayor), 10 community leaders (appointed by district council leaders), 5 representatives of the city’s five Chambers of Commerce, 3 members of City Council and 2 department heads from city government.

After rewriting comes re-mapping. The City Planning Commission now moves to center stage, working with each neighborhood to develop a local master plan. Current land uses are mapped, as are proposed changes. The new map must first be approved by the community, and later at public meetings of the Planning Commission and City Council before it gains the force of law.

(No zoning change, however, can take away an owner’s right to continue using their property as they did before the change.)

You can view the city’s current zoning maps at http://citymaps.phila.gov/zoning/.

How long will it take? Re-mapping took 9 months per neighborhood when conducted in Pittsburgh, and it rarely goes off without controversy. As always, clashes occur between business interests and those who defend neighborhood quality of life.

Yet with strong support on all sides for Question 6, the time seems right to balance these interests. The referendum question itself sets the tone, promising to both “encourage development” and “protect the character of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods.”

“We’re looking forward to a real intelligent conversation with residents, neighborhood civic associations, universities, and institutions,” said developer Bob Rosenthal. “Not everybody is an expert in zoning. But neighbors know what they like when they see it. And they know when they don’t.”

Next: How other cities have reformed their zoning codes

Matt Blanchard is a former reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer who now teaches at the University of the Arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.