New Philadelphia emergency unit responds to overdoses in Kensington

A new emergency unit pairs paramedics, social workers in answering overdose calls in Kensington. Local officials say it’s the first of its kind in the U.S.

Social worker Shane Randall (Nina Feldman/WHYY)

Every morning at 8 o’clock, social worker Shane Randall gets an email telling him which addiction-treatment facilities have available beds that day.

But Randall doesn’t work for a rehab facility, or for a homeless-services organization. He works for the Philadelphia Fire Department.

His job is a part of a new partnership between the Fire Department and EMS and the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services to create an emergency-response unit specifically designed to handle overdoses. Officials here say it’s the first of its kind in the country.

Each day from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., a paramedic and a case manager will be paired together to respond to overdose calls as they come in. Known as AR-2, the unit will roam the Kensington area between calls, where its staff will do outreach work and be available if anyone in the area wants to approach them about access to treatment. The unit also will take people to the hospital when appropriate, or directly to a rehabilitation or treatment facility. It’s Randall’s job to figure out the best placement for the individual.

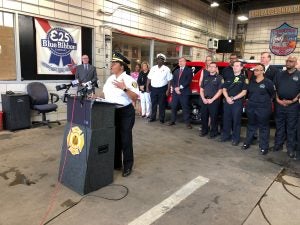

“It’s about meeting people where they are,” said Mayor Jim Kenney, who expanded the Fire Department’s budget to help pay for the program. “If a patient is not ready to enter a treatment facility, AR-2 will offer free naloxone and information on how to access care when they are ready.”

Kenney said he hoped the initiative would increase trust between community members and the medical community, and remove barriers to treatment. The bulk of the program is being paid for with a $2 million grant from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), awarded to the city Department of Public Health.

Crystal Yates, assistant deputy commissioner of emergency medical services, said the idea emerged after hearing from her field medics that they felt like they weren’t doing enough to help.

“They were taking people with substance-abuse disorder who overdosed to the hospital, and then they would see that same person again maybe later that day or the next day,” Yates said. “They felt like they weren’t making a difference.”

The Philadelphia Fire Department responds to roughly 744 EMS calls every day — 5% of which are classified as overdoses. That means 37 overdoses a day.

The program was piloted in April and engaged 25 people in the first six weeks, six of whom accepted treatment. Those are small numbers in proportion to the overall number of overdose calls the department receives, but Fire Commissioner Adam Thiel said that’s because each case takes hours to process.

“We’re not just gonna do a fire and forget, and literally or figuratively put a Band-Aid on it or give them Narcan,” said Thiel. “That’s what hasn’t been working. There’s a lot of Narcan out there, it simply isn’t enough. We had to think of this in a different way.”

When an overdose is called in, the AR-2 unit will arrive on the scene in addition to an ambulance or other emergency response vehicles. If it’s the type of case the new alternative-response unit can handle, it can release the other emergency response units back into the system so they’re available for other calls.

A similar program in partnership with the University of Pennsylvania has been running since September 2018, with Penn workers responding to less serious cases in the West Philadelphia area.

Thiel said that program, known as AR-1, has offset more than 400 EMS emergency ambulance transports, which he called a scarce resource in Philadelphia.

“Heretofore, our options have been fairly limited,” he said. “Somebody calls 911, we take ‘em to the hospital.”

The SAMHSA grant also allowed the departments to hire an epidemiologist, Emily Bobyock, to track and consolidate data among the various departments and measure the program’s success.

Bobyock said that initially she will look at how many contacts the unit makes, the nature of the contact (whether the unit is being flagged down, stops when it sees someone in distress, or is arriving as a secondary to a medic unit), and how many doses of Narcan are left behind, as well as outcomes such as how many people are accepting treatment and remaining there. Kenney said they will report on the initiative’s progress next month.

Randall, the social worker, said the program has already streamlined the process for getting people into treatment. “Before, an individual may have had to wait hours, maybe even days to get into rehab. We’ve cut all that red tape in half.”

The moments after an overdose can be a tricky time for a person to make a big decision like entering treatment, Randall said. Assuming that person has just been given Narcan, it means he or she will have been under the influence and could become high again if the Narcan wears off.

Sometimes people accept treatment, and sometimes they don’t, Randall said. The idea of the new unit is to be there whenever they’re ready.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.