New Jersey joins Pa., Del. in screening newborns for a potentially deadly genetic disorder

New Jersey joins Pennsylvania and Delaware in testing babies for spinal muscular atrophy. But the test catches only 95% of cases.

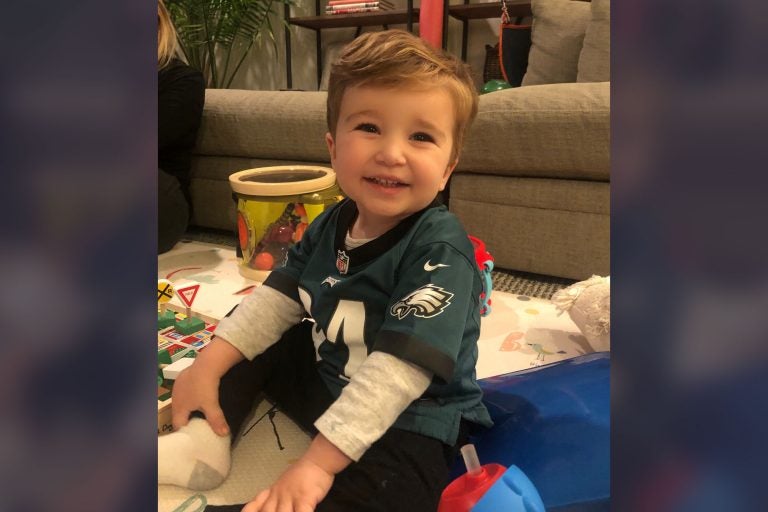

Shane Phillips (Courtesy of Regina Phillips)

By most measures, Shane Philipps was born a healthy New Jersey baby in January 2018.

When doctors took blood from Shane’s heel to test him for almost 60 medical conditions, called a newborn screening, the reports offered no reason to be concerned. In his first months, he was alert and could lift his head up while on his belly.

But after Month Six, Shane’s mother, Regina, would find herself on a monthslong journey to find out why Shane could not sit up on his own and why he was moving less.

“We were first-time parents and everyone just said, ‘You know, he’ll move when he’s ready, he’ll hit his milestones when he’s ready, he’s just chunky,’” she said.

It wasn’t until Shane had almost turned 11 months old that his mother would have a diagnosis. Shane had spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, a genetic disorder that causes the loss of motor neurons and muscle weakness.

By that point, Shane had the muscle tone of a newborn.

“He could barely lift his arms up to his mouth to feed himself,” said Philipps. “He wasn’t able to lay on his stomach anymore and lift his head up at all. He had basically regressed to a newborn in terms of his motor function.”

Had Shane been tested for SMA at birth, Philipps believes the disorder’s attack on her son’s body could have been treated before it caused more damage.

Ironically, a bill to add SMA testing to New Jersey’s newborn screening had been introduced in the Legislature 10 days before Shane was born, at the request of another mom who benefited from early detection, but the bill hadn’t moved in more than a year.

In March 2019, Philipps contacted Sen. Troy Singleton to tell him Shane’s story in an effort to move the legislation forward. She would then lobby members of the budget committee, where the proposal had been stuck since summer 2018.

Philipps said her efforts paid off this week, when Gov. Phil Murphy signed the bill into law. Babies in New Jersey will be tested for SMA starting this summer.

Elizabeth Kichula, a pediatric neurologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who treats SMA patients, welcomed the announcement but offered a warning.

It’s important to screen early, she said, because SMA is hard to diagnose once children start presenting symptoms.

Low muscle tone, or hypotonia, is a “common complaint which every pediatrician and every neurologist sees a lot of,” according to Kichula. A doctor may not immediately think to test and treat for SMA.

Part of the problem with getting an accurate diagnosis as children get older is the fact that doctors don’t know what to look for because it’s so rare.

The organization Cure SMA estimates that nine children are born with the disorder in New Jersey a year. The muscle weakness it causes can be deadly to children if not caught in time, because it affects respiratory muscles as well as arms and legs.

Though there have been breakthroughs in treating SMA — the Food and Drug Administration approved a new treatment for the disorder not long ago — early detection is key, said Kichula.

“Once those motor neurons die, we don’t have any way to bring them back,” she said. “But we can rescue those motor neurons that are sick.”

Pennsylvania started testing for SMA in newborns last March, and already, Kichula said, she’s noticed a change in her cases.

“We aren’t seeing the same number of patients that used to present in critical condition, often needing breathing support by the time we diagnose them,” she said. “Now, we’re really able to start the treatments earlier, and in many cases avoid these types of significant life-threatening complications.”

The need for treatment before patients present symptoms is part of the reason former U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar recommended that states add SMA testing to newborn screening in 2018. But states aren’t bound by the recommendation.

Pennsylvania and Delaware are two of the 16 states that already screen newborns. New Jersey joins 15 states that are about to implement the test. Several other states are working on pilot programs.

And obstetricians are increasingly offering a prenatal SMA test, according to Kichula.

Still, the screenings can only diagnose 95% of SMA cases.

“Sometimes, patients hear that they have a negative screening test and they feel that they don’t need to worry about it, even when there are clinical signs,” said Kichula. “I think just that acknowledgment of what you’re testing, and what the limits are, is really important to know.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.