N.J. officials finally release data on bail reform. Their conclusion? It’s working

N.J. officials release data showing bail reform cut jail populations without a spike in recidivism. But they note it didn’t reduce racial disparities.

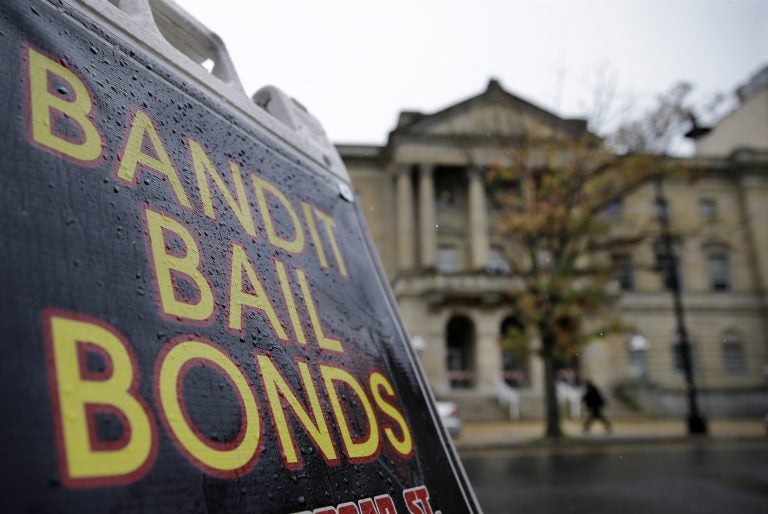

A sign marks a bail bonds businessman across the street from Mercer County Criminal Courthouse in 2014 in Trenton, New Jersey. (Mel Evans/AP Photo)

Updated 4:37 p.m.

Rates of recidivism and failure to appear for court increased slightly after New Jersey virtually eliminated cash bail in 2017, according to a report released Tuesday by the state Judiciary.

The data was viewed as a victory by state court officials, who said the increases were statistically insignificant and suggested critics were wrong to predict that releasing more nonviolent criminal defendants before their trials would wreak havoc on the justice system.

And it seemed to provide an answer to a key question from supporters and critics of New Jersey’s ambitious new setup: Does it work?

Criminal justice reform “is working as intended,” the report said. “Concerns about a possible spike in crime and failures to appear did not materialize.”

The report was the first comprehensive analysis of the reimagined N.J. criminal justice system, which advocates have looked to as an example since the state drastically reduced its reliance on cash bail more than two years ago.

Backers cheered the report’s conclusions.

“We have confirmation that people are still showing up in court, and they’re getting rearrested at the same rates they did under the money bail system,” said Alex Shalom, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU of New Jersey. “That’s an unmitigated victory.”

Under the law, which took effect in January 2017, judges stopped issuing money bail to every criminal defendant and instead decided whether people should remain in jail before their trial based on the risk they posed to the public.

Jail populations dropped. Fewer poor defendants — who could not afford even modest bail amounts — remained behind bars.

The new rules also allowed judges to detain more violent offenders in jail with no chance of walking free before trial.

“New Jersey’s jail population looks very different today than it did when the idea of reforming the state’s criminal justice system first took hold,” said Judge Glenn Grant, acting administrative director of the courts, in a statement.

“The state’s jails now largely include those defendants who present a significant risk of flight or danger to the community,” he said. “Low-risk defendants who lack the financial resources to post bail are now released back into the community without having to suffer the spiraling, life-changing consequences of being detained for weeks and months while presumed innocent.”

Opponents in the bail bonds industry and elsewhere have suggested that allowing criminal defendants to roam free shortly after arrest would result in more crime and fewer people showing up for court. Critics say what was considered “reform” by then-Gov. Chris Christie and his allies in the Judiciary and Legislature diminishes the rule of law and puts residents at risk.

Yet new data shows only modest increases in two of the main measurements of success since 2017.

In that year, 26.9 percent of defendants released from jail before their trials were charged with a new crime — either an indictable offense or a disorderly persons charge. That number increased from 24.2 percent in 2014.

Some 89.4 percent of defendants appeared for their court dates in 2017, down from 92.7 who showed up in 2014. Analysts cautioned that “small changes in outcome measures should be interpreted with caution and likely do not represent meaningful differences.”

The report also found that many more low-level defendants are now being released immediately on summonses rather than being issued warrants and booked into jail first.

Opponent questioned whether those who remained in jail were the people that N.J. officials wanted to help when they revamped the criminal justice system.

“I don’t know that the composition of poor people in jail has changed. Twenty percent of them are getting preventive detention. Are those poor people? We don’t know,” said Jeff Clayton, executive director of the American Bail Coalition.

“I’m unconvinced of the equities here, that they’ve made some giant leap other than in their own minds,” he said.

The results were not all positive, according to the report. Although the state’s jail population dropped by 44 percent between the end of 2015 and 2018, changes to the criminal justice system apparently had little impact on racial disparity among incarcerated people.

Black men made up 54 percent of the state’s jail population last year, the exact same share as in 2012, long before the elimination of cash bail.

“The overrepresentation of black males in the pretrial jail population remains an area in need of further examination by New Jersey’s criminal justice system as a whole,” the report said.

New Jersey Criminal Justice Reform Report 2018 by M D'Angelo on Scribd

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.