Federal court ruling leaves New Jersey’s bail overhaul in place

The reconfigured pretrial justice system virtually eliminates money bail in favor of methods that aim to ensure defendants on release stay out of trouble and show up for trial

Listen 4:34

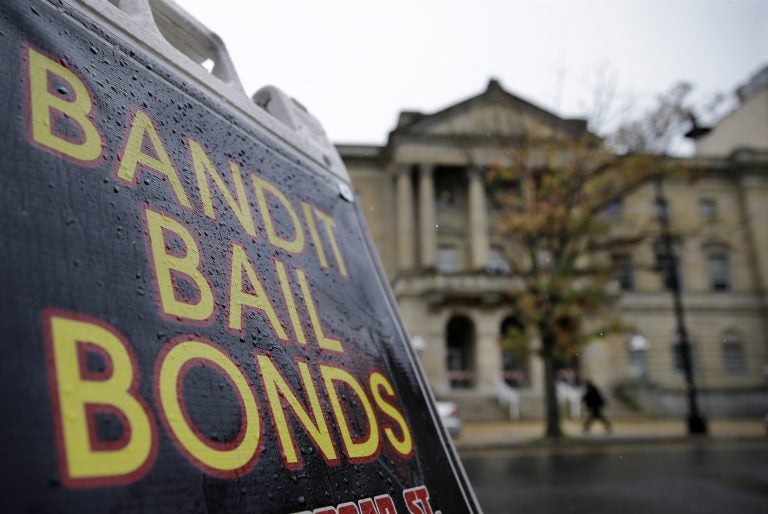

A sign marks a bail bonds businessman across the street from Mercer County Criminal Courthouse in 2014 in Trenton, New Jersey. (Mel Evans/AP Photo)

A federal appeals court panel ruled Monday that criminal defendants do not have a constitutional right that guarantees them the option to pay cash bail to obtain their freedom before trial.

The ruling leaves New Jersey’s ambitious bail overhaul in place, and it deals a blow to the bail bonds industry that had been fighting the changes to the state’s criminal justice system.

Monday’s ruling came out of a federal lawsuit filed by Brittan Holland, who was arrested and charged with aggravated assault in 2017 for his alleged role in a bar fight.

In the past, a judge may have given Holland money bail, which he could have paid to go free. Holland could have awaited his trial from home.

But under New Jersey’s bail overhaul, which began in January of 2017, Holland was released under non-monetary conditions. A judge placed Holland on house arrest and made him wear a GPS monitor. Holland never had to pay bail.

New Jersey’s reconfigured pretrial justice system virtually eliminates money bail in favor of other methods that aim to ensure criminal defendants on release do not commit another crime or skip a future court date. Often judges require defendants to check in regularly with court staff or — in the cases of defendants suspected of more serious crimes — place them under home detention and track their movements.

The overhaul also allows judges to incarcerate any defendant deemed too great a risk to be released, which the courts could not do before.

Championed by former Gov. Chris Christie, the chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court, and countless lawmakers, the overhaul aimed to benefit poor defendants too destitute to pay even small bail amounts and also empower judges to keep particularly dangerous defendants behind bars before trial.

Holland sued the state after his release, claiming that the state violated what he saw as his constitutional right to pay cash bail to secure his freedom, instead of being released under what he considered burdensome restrictions.

The three-judge panel of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Philadelphia ruled against him.

Even if the Eighth Amendment (which guards against “excessive bail”) is interpreted as guaranteeing a right to bail, the judges wrote, that does not mean a defendant automatically gets to pay money to go free before trial.

The “question key to Holland’s contentions is whether there is a federal constitutional right to deposit money or obtain a corporate surety bond to ensure a criminal defendant’s future appearance in court as an equal alternative to non-monetary conditions of pretrial release,” the opinion reads. “Our answer is no.”

It affirms a September ruling in New Jersey District Court that also denied Holland’s motion for a preliminary injunction, which would have brought the state’s cash bail overhaul to a screeching halt while Holland’s case moved forward.

An attorney for Holland could not immediately be reached for comment. It is unclear if Holland will appeal the ruling.

The judges also ruled that the Lexington National Insurance Corporation, a Maryland-based bail bonds company that is also a plaintiff in the case, does not have legal standing.

Proponents of New Jersey’s cash bail overhaul applauded the ruling as an endorsement of the state’s new system.

“It’s the second court that has said the same thing, which is that New Jersey was well within its rights to create a system that de-emphasized the use of money bail,” said Alex Shalom, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU-NJ, which filed a friend-of-the-court brief in support of the state.

“Cash bail hurts poor people. Cash bail has deleterious effects on fairness, on public safety, and on justice,” Shalom said. “The court recognized that.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.