N.J. county defends ICE agreement after rebuke from state AG

Forty out of nearly 8,000 inmates processed at the county jail in 2018 were found to be undocumented immigrants and turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

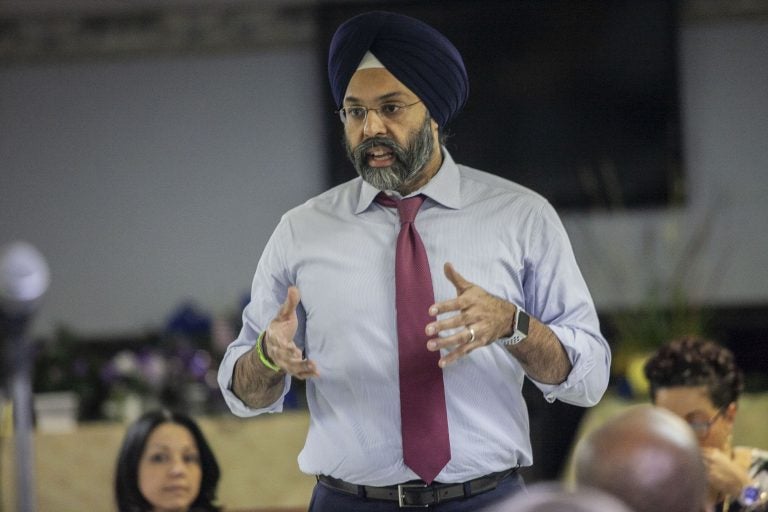

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal (Miguel Martinez for WHYY, file)

Monmouth County is defending its decision to quietly renew a program that helps identify and deport undocumented immigrants. It’s justifying it actions after the state attorney general’s office sharply criticized Monmouth and Cape May counties for not disclosing their continued cooperation with federal immigration officials.

Monmouth County Sheriff Shaun Golden said he was “hopeful” the state would let the program continue in the county jail after threatening to shut it down earlier this week. Through the program, designated jail staff are trained to take on duties normally performed by federal immigration officers.

“Cooperation from the federal, state and local level is essential when protecting the public and ensuring that dangerous, undocumented immigrants are not released from jail in order to maintain the safety of our communities,” Golden said in a letter dated July 9 and acquired by WHYY.

Forty out of nearly 8,000 inmates processed at the county jail in 2018 were found to be undocumented immigrants and turned over to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Golden added in a statement Wednesday.

In a pair of sternly worded letters sent a few days earlier, a top official in Attorney General Gurbir Grewal’s office accused the sheriffs in Monmouth and Cape May counties of violating a new “Immigrant Trust Directive” that seeks to limit cooperation between local law enforcement and ICE.

The directive requires that counties get the attorney general’s approval before renewing what are known as 287(g) agreements, which delegate local law enforcement officers to screen inmates for immigration offenses.

Both counties renewed their agreements shortly before the directive took effect on March 15. But the “clear implication” of the directive was that they needed approval to do, Division of Criminal Justice Director Veronica Allende said in the letters.

The fact they didn’t disclose the new contracts until after the attorney general’s office learned of them from a news reporter last week “suggests that you deliberately declined to disclose this information,” Allende wrote.

Allende said the counties have until August 6 to justify why the programs should remain in effect or else the attorney general will shut them down. The counties must also hold a public hearing on the program, she said.

Golden said his office would provide the attorney general’s office with more information by July 30 but did not mention plans for a public hearing.

Cape May County Sheriff Robert Nolan did not respond to multiple requests for comment Wednesday.

Nationally, about 90 law enforcement agencies in 21 states — mostly county jails — let their officers be trained by ICE to screen people for their immigration status and turn over undocumented individuals to ICE custody.

ICE says on its website that those local law enforcement officers serve as a “force multiplier” that last fiscal year helped identify more than 2,000 undocumented immigrants convicted of crimes ranging from assault to homicide.

“The efficiency and safety of the program allows ICE to actively engage criminal alien offenders while incarcerated in a secure and controlled environment,” ICE says.

Law enforcement officials are divided over the effects of the program. Attorney General Grewal, as well as many immigrant rights activists, argue it can actually make communities less safe by undermining the trust between immigrants and police.

“Communities depend on everyone in their city or township to report a crime, to be witnesses of crimes, to be able to collaborate with police when there’s an issue in a community,” said Johanna Calle, director of the New Jersey Alliance for Immigrant Justice. “And when immigrant communities believe that local law enforcement are going to be working with ICE, they going to not do that.”

The Monmouth and Cape May county sheriffs are Republicans in red counties. But ICE contracts have also become flashpoints in Democratic strongholds such as Bergen, Hudson and Essex counties.

Those counties make millions of dollars a year housing federal immigrant detainees at their jails, and officials there have stuck with the contracts despite blistering criticism from residents and activists.

Even counties without formal agreements with ICE have become embroiled in debates over immigration. The Sussex County board of freeholders, controlled by Republicans, recently voted to place a question on the November ballot to let voters decide whether the county sheriff should follow Grewal’s Immigrant Trust Directive.

Grewal has said ignoring the directive would be illegal and gave officials there until the end of this week to respond to his request not to include the question on the ballot.

Golden, the Monmouth County sheriff, said the 287(g) program is “highly regarded and essential” and “is not meant to undermine community trust” since it is used only at the county jail on incarcerated individuals.

Besides Monmouth and Cape May, Salem County also had a 287(g) program in place. That agreement expired last month and it does not appear officials there renewed it.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.