More vacant property than can be filled in Lower North Philadelphia

The in-the-works comprehensive district plan will likely call for some formerly residential or commercial areas to be cleared and turned over to other uses, such as farming.

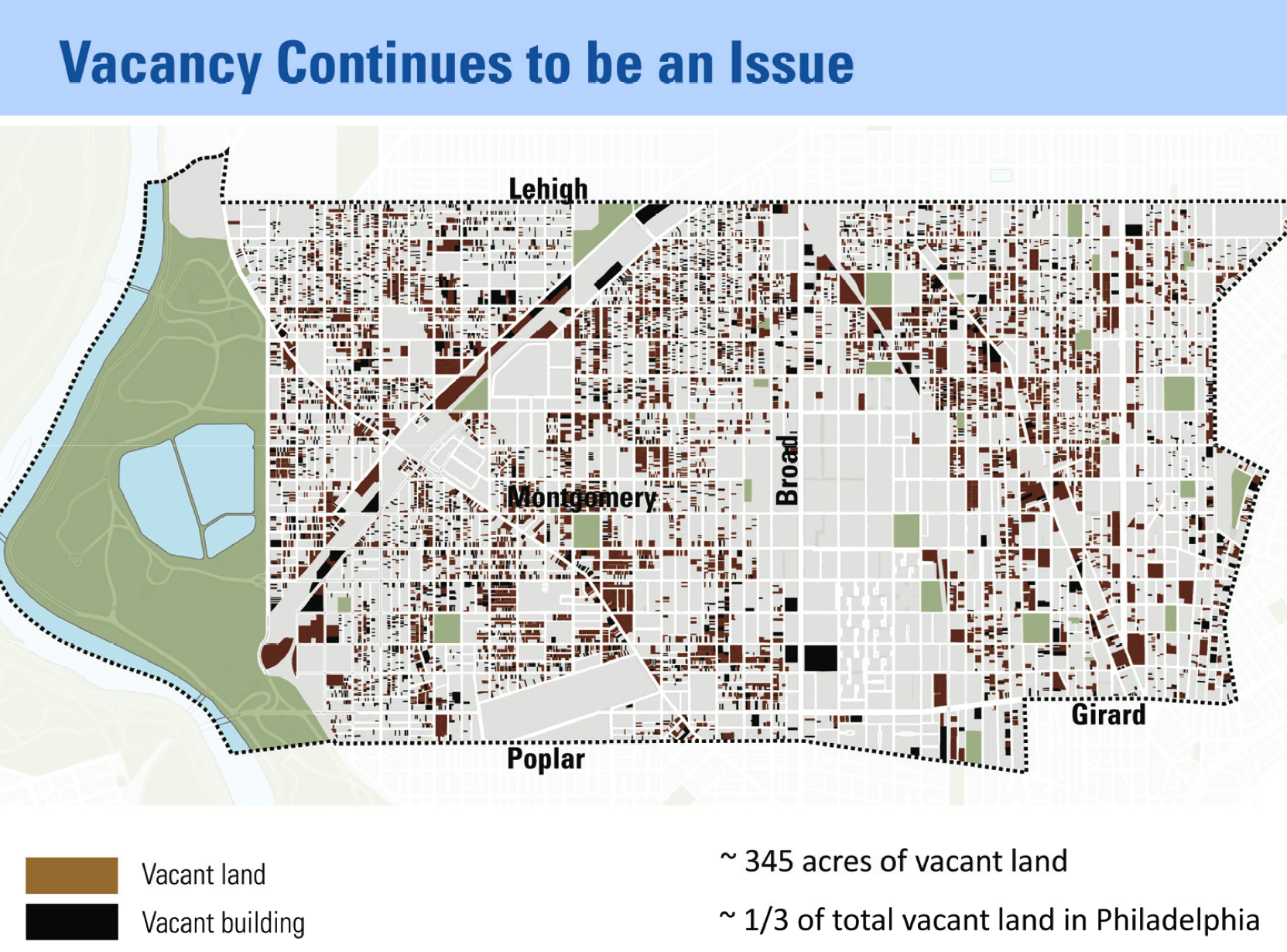

City planners have begun work on a blueprint for the future of Lower North Philadelphia – a collection of neighborhoods with so much vacant property, the district-level comprehensive plan won’t try to fill it all.

Some blocks in North Philadelphia, North Central, Norris Square, Olde Kensington, South Kensington, West Kensington, Yorktown, Ludlow, Brewerytown, Green Hills, Cecil B Moore, Sharswood and Strawberry Mansion have so few people living in them that it may make more sense for the city to buy out the few remaining residents and use the land for something else, such as farming, said planner and district plan manager David Fecteau.

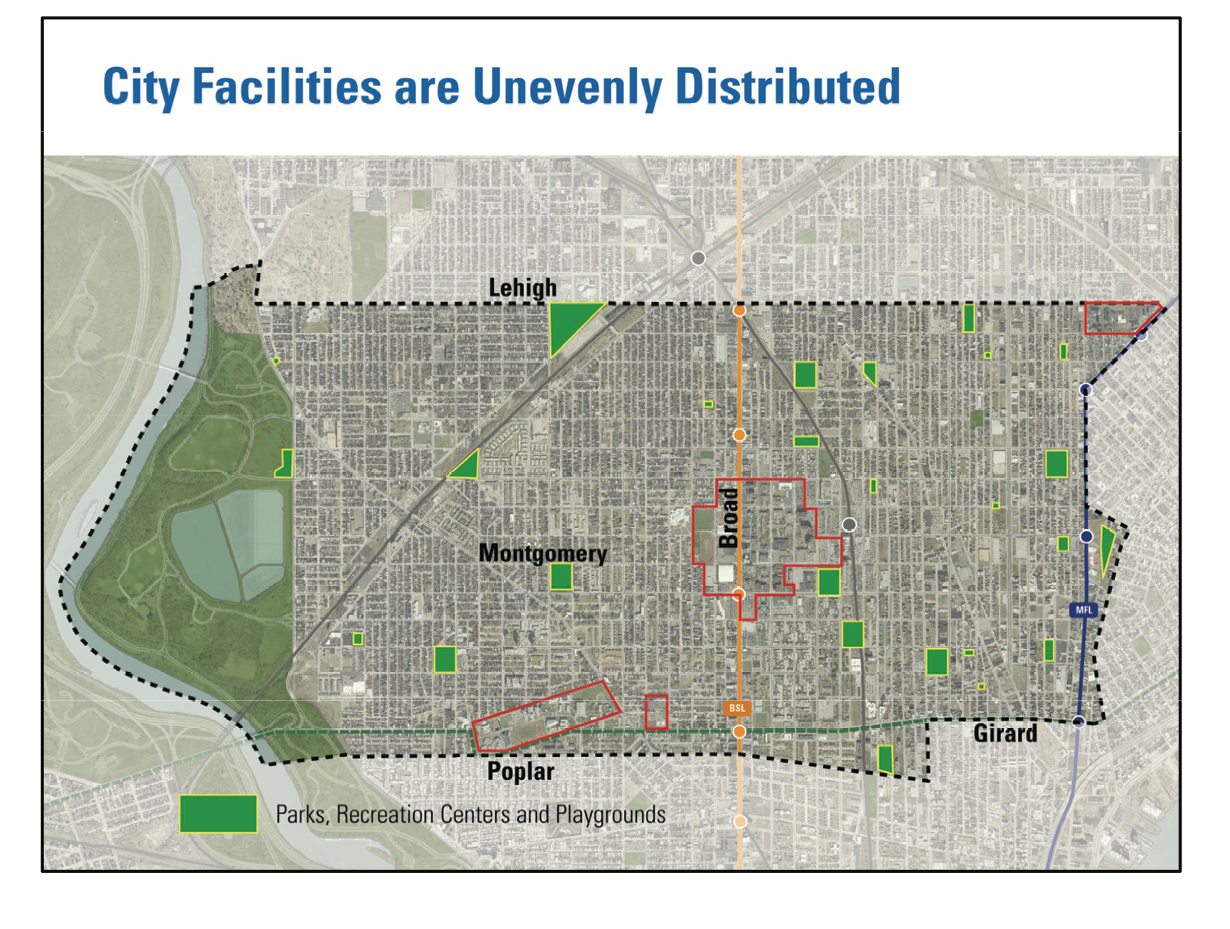

Some parks and recreation spaces are in such poor shape, the best choice may be closing them and focusing resources on those that remain open, or on new facilities that take the place of several shuttered old ones.

“The situation is there’s a slowly growing population and a lot of unused land,” Fecteau said. The hardest part of the planners’ work “is going to be convincing people what the reality is,” he said.

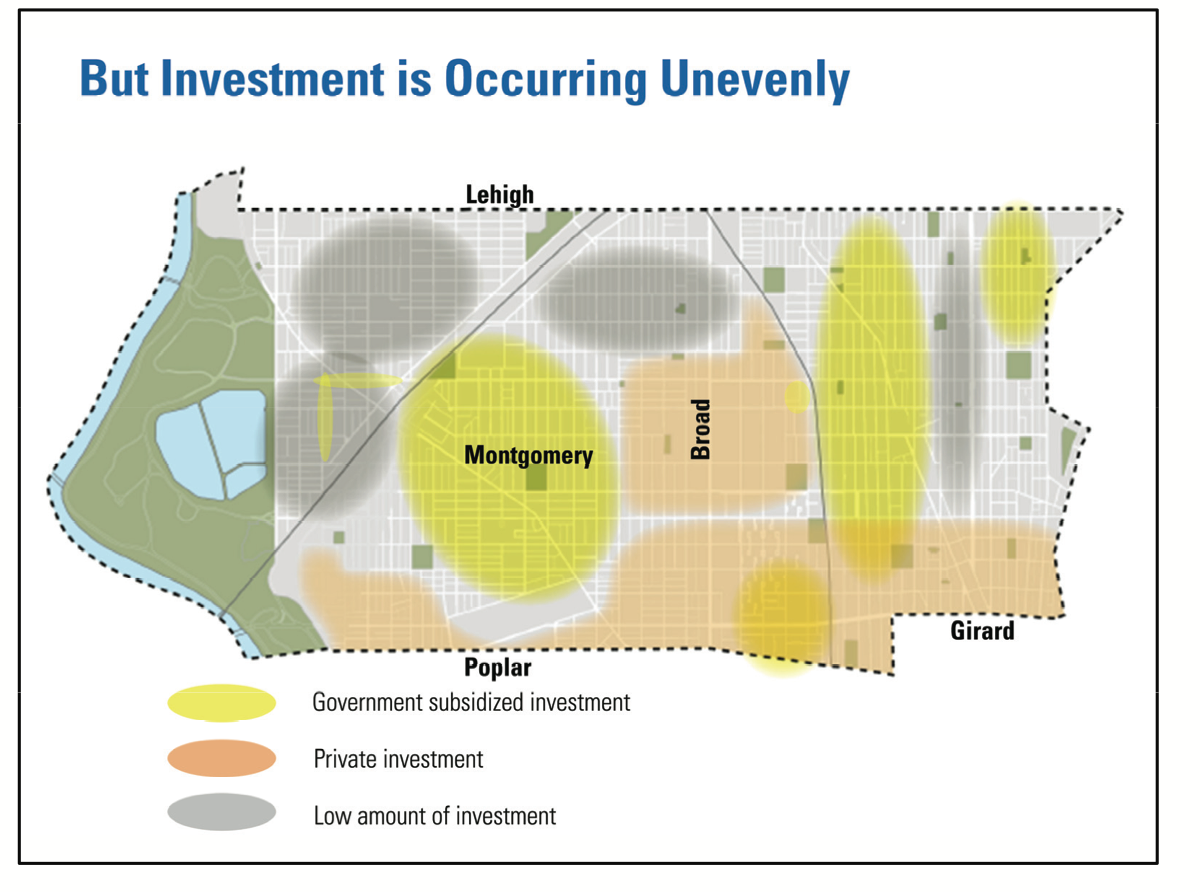

Condensing the area where people live and consolidating some services doesn’t mean life will be gloomy in the future, though. The idea behind concentrating residential, recreation and commercial areas is to concentrate investment.

“Overall, it’s going to be smaller than it ever was, but we want to see it improve,” Fecteau said. “Smaller, but better.”

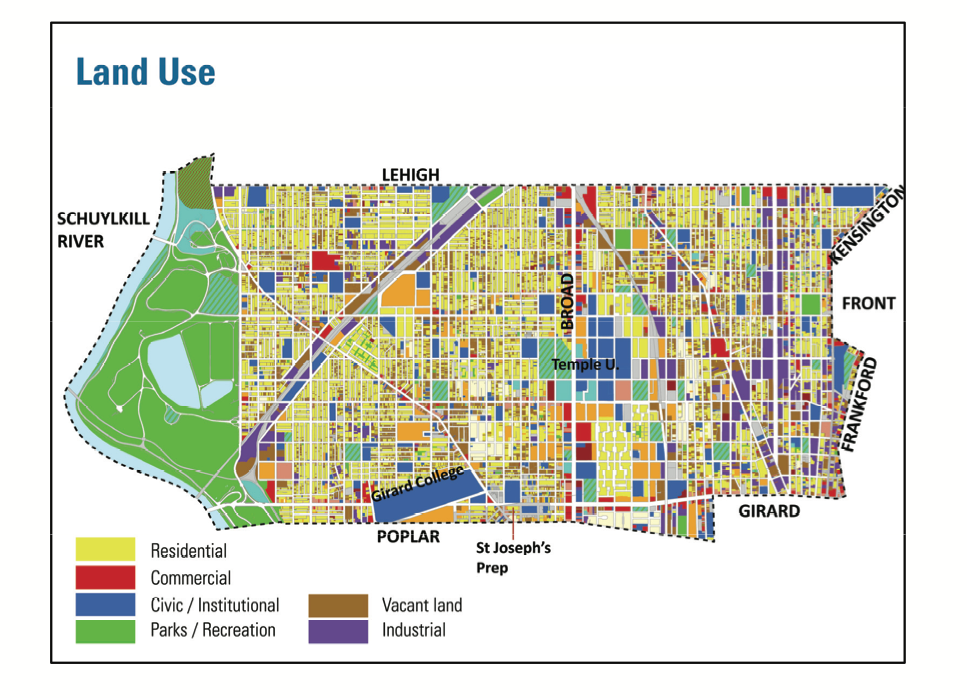

Lower North Philadelphia has some huge assets: Temple University; 19 bus routes, four El stops and two regional rail stops; proximity to Center City, proximity to Fairmount Park and other parks and recreation centers and libraries.

But it has huge challenges: While showing slight growth in recent years around Temple, the population has plummeted since its peak in the 1950s. Current median household income is $16,459. When adjusted for inflation, that represents a 10 percent drop in income since 1980.

“We have a situation where 47 percent of the population is in poverty,” Fecteau said. “Overall, there’s been an increase of jobs that require lower skills and pay less, and a decrease in jobs that require higher skills and pay more.”

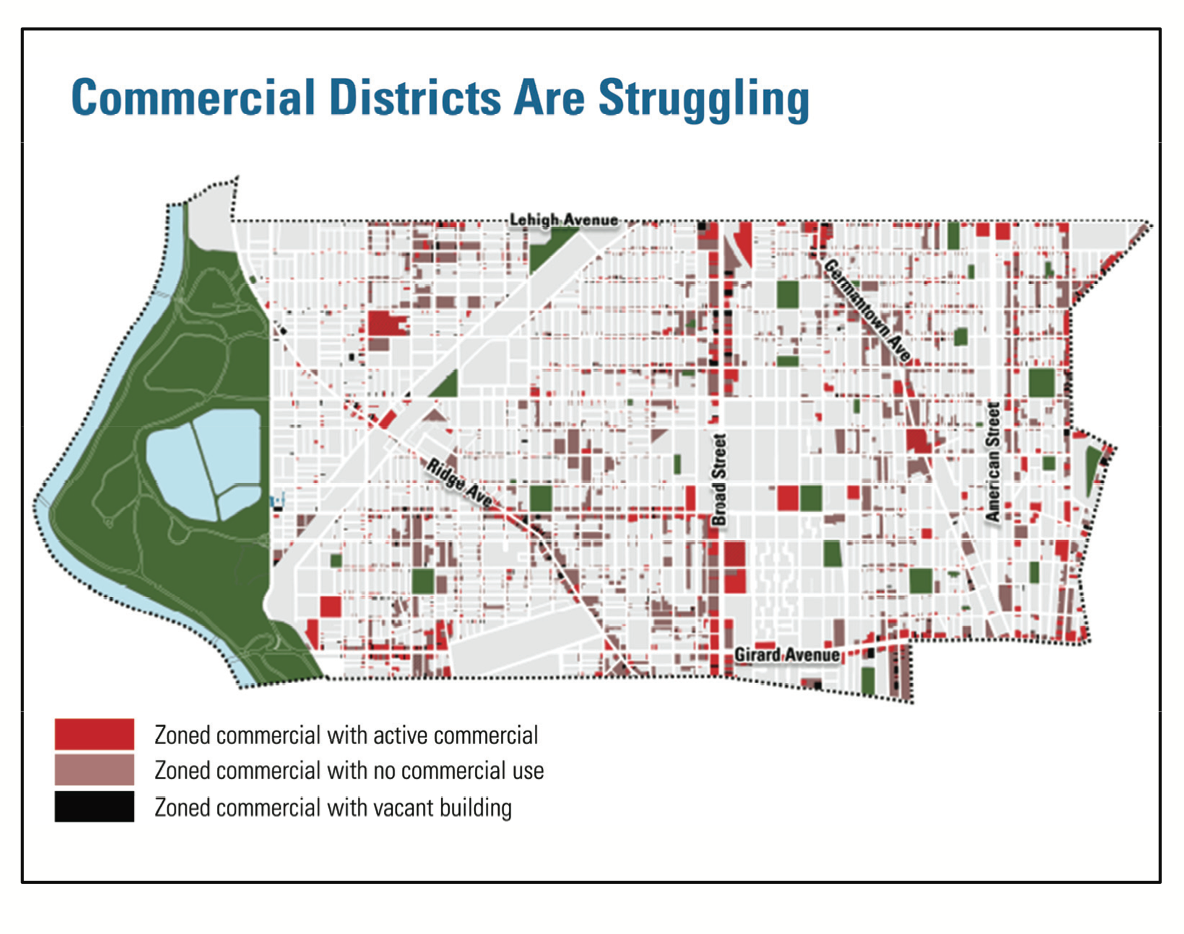

Some commercial and industrial parts of the district remain healthy, while others are mostly empty, Fecteau said. American Street is an example of both. A lot of businesses that once thrived there are gone, but “We’re trying to hold onto sections” that remain vibrant.

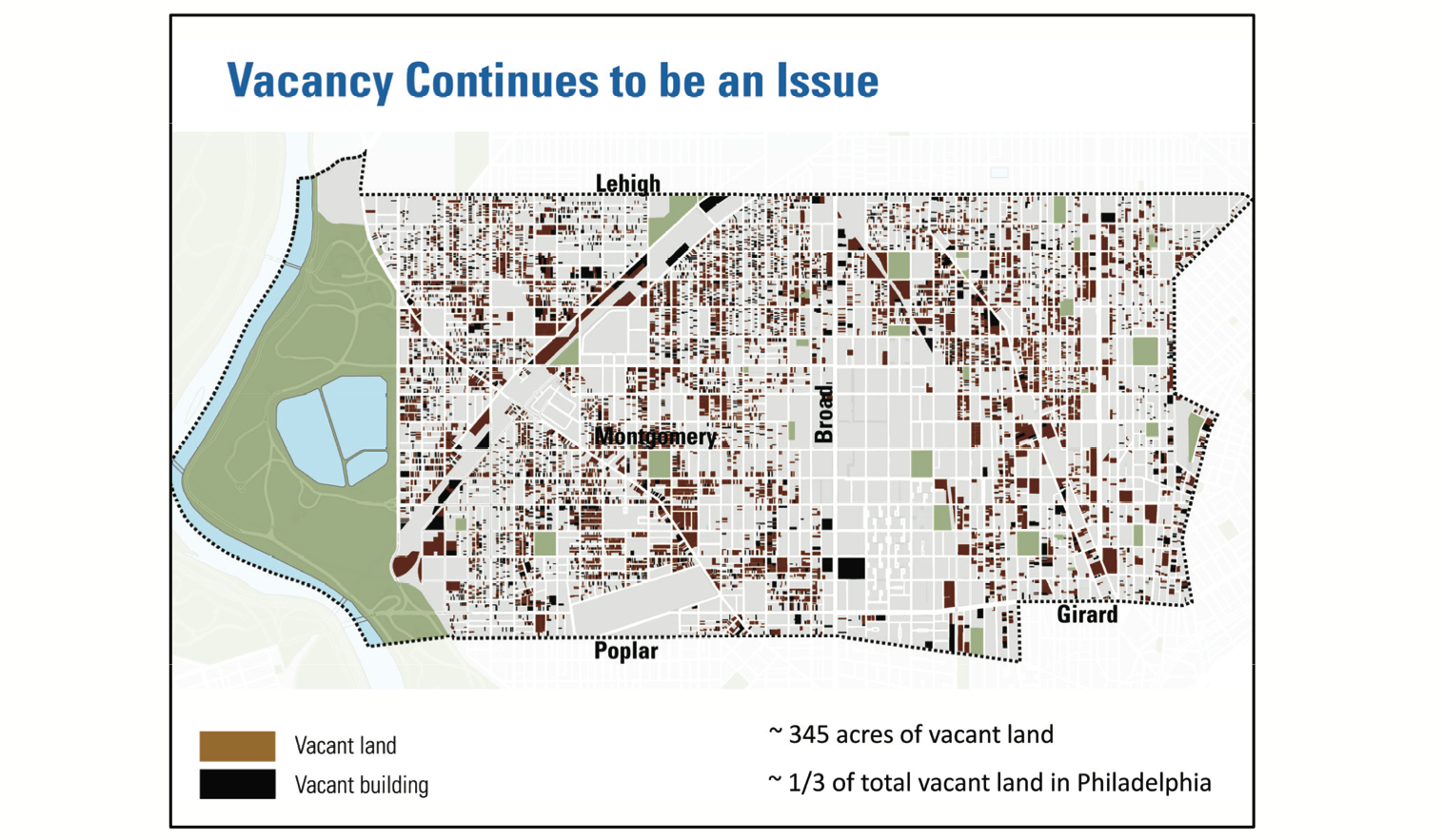

It’s the decline in population that precipitated the abundance of vacant buildings and land. In Lower North Philadelphia, 13 percent of properties are vacant. There are about 4,000 vacant buildings, 80 percent of which were once residential or partly residential. There are 10,600 vacant lots, 40 percent of which are owned by the city or city-related agencies.

“What we have is a lot fewer people living in the same area,” Fecteau said.

Lower North Philadelphia also has 45 “ghost parks,” parcels of land, mostly the size of housing lots, that were once parks, or slated to be parks, but now are abandoned, and, like other vacant property, often home to dumping and other problems.

“If vacancy were a land use, it would be the third largest use in the district,” Fecteau told members of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission at this week’s meeting.

In the past, Fecteau noted, the city has redeveloped vacant parcels with low-income housing, often built in single-family, suburban style. The thought behind that choice was that it gave people with lower incomes a chance to live in a style of home they might not otherwise have. That building style also sucks up a lot of space, he said.

But in the Lower North low-density housing could jeopardize public transit, Fecteau said, and transit is critically important in a place where 58 percent of households have no cars.

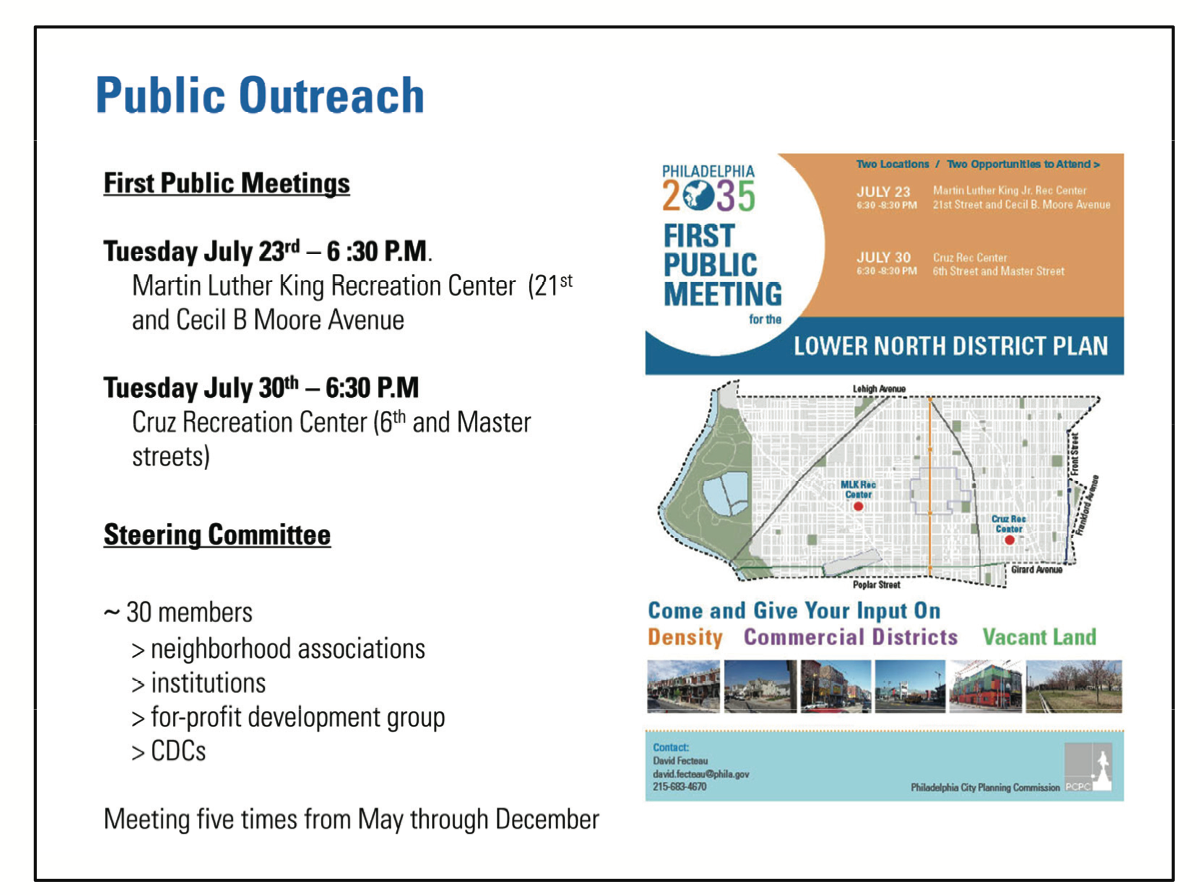

Fecteau and his team have been compiling research and meeting with a steering committee consisting of community leaders, business owners, non-profit organization representatives and elected officials. Later this month, the first two community meetings will be held to start finding out from residents what they want for their neighborhoods, and get their opinions on these tough issues.

Fecteau said planners will be talking to people who live on blocks with very few neighbors. “We’re going to ask one very blunt question: Do you like the situation?”

If neighbors like this “semi-rural” state, Fecteau said, the decision may be to leave that block alone. But if not, land not being used might be condemned and “we could try to force some type of redevelopment.”

But there are just too many pockets like this to redevelop all of them, so there might be situations where houses come down and the land is vacant. “What can city government do about it? We can save that land, and set it aside for something else,” he said. “So what is acceptable for that something else? That’s one of the things we are trying to get at (by talking to residents and community leaders). Could we lease it to someone who wants to farm? Someone who wants to stable horses?”

Some uses may be impossible because of land contamination or zoning problems, or simply lack of demand, he said.

Just holding the land in city hands is a tough option. “With declining governmental revenue, it’s more of a challenge. If we take over land, we are responsible for maintaining it,” he said.

“Clearly, this group is going to grapple with some of the hardest problems that major cities face,” Deputy Mayor and Commission Chairman Alan Greenberger said after Fecteau’s presentation to the planning commission. Because of the intense vacancy, poverty and crime issues parts of the district face, Greenberger urged Fecteau to work with other groups that are addressing those issues already. Fecteau and the other staffers working with him have worked with some organizations already, and Greenberger compiled a list as he listened to Fecteau speaking. Greenberger added a few more after listening to audience member and Strawberry Mansion resident and community leader Judith Robinson speak.

Robinson, a member of the steering committee, said she agreed that the district has many wonderful amenities and benefits. She agreed with many Fecteau mentioned, and added Girard College and the Audubon Society.

“It’s a great location, let’s make something happen,” she said. “Give me some help, you all.”

But Robinson said she didn’t want the neighborhood’s vacant land and other challenges to be leveraged into an opportunity for redevelopment that leads to gentrification. Strawberry Mansion has a home ownership rate of 60 percent, she said, and people who live there now aren’t going anywhere.

Fecteau said there’s no danger that housing demand would exceed available housing – and therefore increase prices – anytime soon.

Commissioner Beth Miller noted that while the planning area includes some well-known neighborhoods, other areas lack an identity. Greenberger said this is a problem in other parts of the city as well – there are places that don’t even have names. “The lack of cohesion is directly related to the problems you are facing,” he said. Greenberger suggested that part of the work ahead of the planning team may be getting residents to chose a name for their neighborhoods, which would help them form an identity.

Fecteau said that when planners have made such suggestions, residents have said with so many other problems, the lack of a name wasn’t high on their priority list.

The first two Lower North District Plan public meetings will be held July 23rd, 6:30-8:30 at Martin Luther King Jr. Rec Center, 21st Street and Cecil B Moore Avenue and July 30th, 6:30-8:30 at the Cruz Rec Center, 6th Street and Master Street.

Both sessions will cover the same material.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.