‘A greater nation’: Street renaming commemorates MLK speech in West Philly

Martin Luther King Jr. came to the city in August 1965 as part of a protest campaign targeting big cities up North. His visit included a stop in Mantua.

Philadelphia City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier speaks at the dedication of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Triangle in the 3900 block of Haverford Avenue. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

In August 1965, at the height of the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. stopped in West Philadelphia as part of his “Freedom Now” tour, a celebration of sorts after a successful year that would include the pivotal Selma-to-Montgomery marches and, just three days later, the signing of the Voting Rights Act.

Nearly 60 years later, on a frigid MLK Day, community leaders, neighbors and elected officials gathered in Mantua for a street renaming ceremony dedicated to that piece of neighborhood history and the civil rights icon himself.

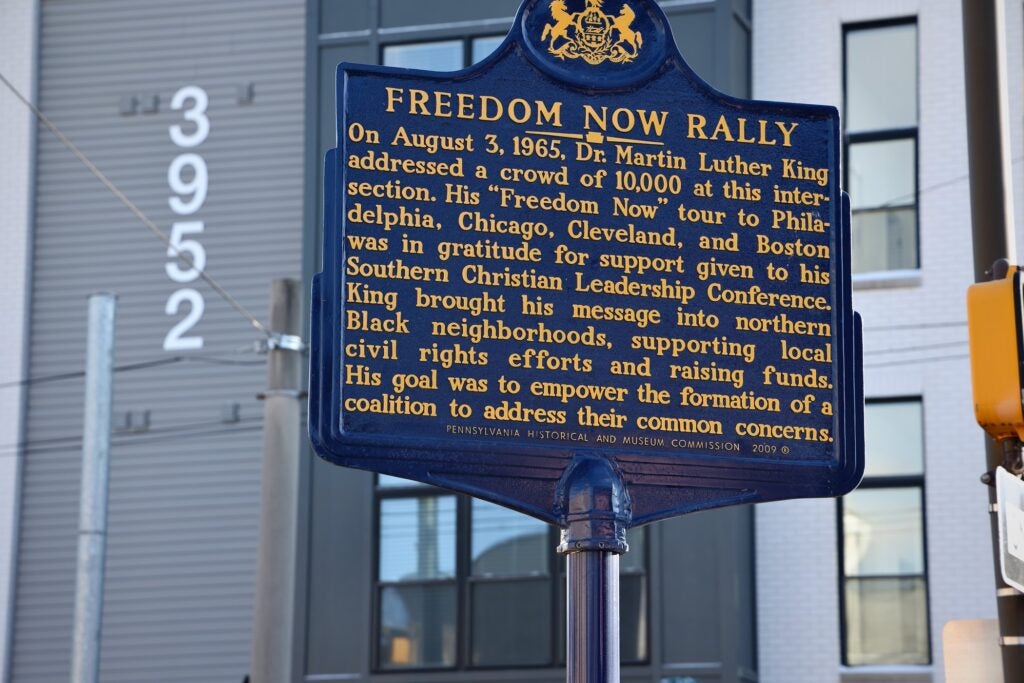

The 3900 block of Haverford Avenue, between Lancaster Avenue and 40th Street, will now be known as the “Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Triangle.” The triangle also features a bust of King, a state historical marker, and a mural memorializing King’s speech.

During Monday’s ceremony, City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier told a small crowd that the newly-minted triangle is “both a recognition of our history and a recommitment to fighting for a future with collective care and liberation.”

“I know that Mantua will continue to show the world that, just like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., we will always be a ‘drum major for justice, peace and righteousness,’” said Gauthier, who introduced the resolution for the street renaming.

The community-driven effort is the latest commemoration of King’s visit to Mantua on August 3, 1965, when more than 10,000 people gathered to hear him speak.

King stopped in Mantua as part of a major protest campaign designed to mobilize people in northern cities, including Philadelphia. The tour also made stops in Newark, New York, Washington, Chicago, and Cleveland.

King hoped his non-violent methods could be used to help address systemic issues to which Black families were subjected in the inner cities, including poverty, housing discrimination and police brutality.

“Now is the time to grant freedom to the Negro all over the United States. Now is the time to make America a greater nation,” King told the massive crowd.

His speech also contained a more personal message for participants.

“I come here from the front lines of the civil rights movement in the South to tell you, ‘You are somebody.’ Let us have a sense of somebodiness. Don’t let anybody make you think that you are not somebody,” said King.

Joe Walker, who helped lead the push to memorialize King’s visit, was just 9 years old when the civil rights leader came to speak two blocks from his childhood home.

Walker does not remember many details from that day, but King’s appearance has stayed with him all these years.

“Martin Luther King was about peace and stood for peace, and I just try to model my life after that,” said Walker after the ceremony.

The day after his speech in Mantua, King addressed another massive crowd at Girard College as part of an ongoing push to desegregate the whites-only school more than a century after it was founded. Girard College has now hosted Philadelphia’s signature MLK Day event for the past 30 years.

On that Friday, then-President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law. Widely viewed as a milestone of the civil rights movement, the landmark measure barred states from denying citizens the right to vote based on race, opening the door for Black and brown communities to fully participate in the country’s political system without the spectre of discrimination.

The law notably led to a surge in Black elected officials, particularly in the South. According to a study released last year by the University of Oxford, Black representation in local governments in the South quadrupled between 1962 and 1980.

Less than three years after King’s speech in Mantua, he was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, shocking the nation and cutting short his tireless work. While King had reason to celebrate before his assassination, Black families still experienced, and continue to experience, inequality after his death.

Community leader Jim Brown, who helped push for the street renaming, was just 4 years old when King was killed. But he grew up hearing stories about his visit to Mantua, which included a meal inside a home on nearby Folsom Street.

In the triangle, he sees a way to keep that moment — and King’s legacy — alive.

“I just hope that they are empowered, encouraged and motivated to … embrace hope,” said Brown.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.